…

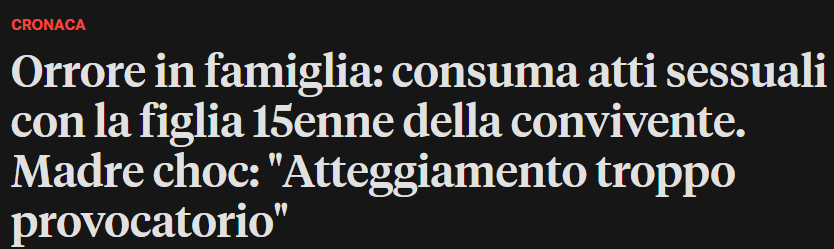

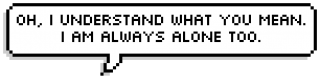

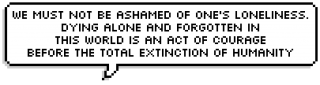

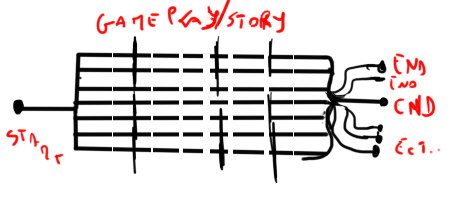

Welcome back to the Tin Coffee Pot Time column, in short a normal “chat” column, or simply topics that are a bit tight in the normal columns that we deal with here in the Archives.

After my sister wrote a nice article on alternative ways of storytelling , making sound and accurate information as it should …

Now I’m going to screw everything up.

As you guessed from the title, “Selfish Confort Dilemma”, this is going to be an evil article. And a lot too. Especially towards you, our readers.

Because we will talk directly about all of us , about how we tend to approach not only the video game, but the entire fictional work in general! I will finally involve you in my speeches and we will no longer be the ones who “talk about games that are now dead”!

Too bad, since you are with me today, this will be done in the ugliest, most insensitive, cynical and at the same time angry way of all these years this site has formed.

And this intent is not at all noble, how will we pursue it?

To keep in line with the genre of games we talk about in the Archives, today we will analyze three titles; including two very… Or even too much loved ones. But we will analyze them on a moral level.

Ah, moral. The one we all like to talk about, including me, because it only relies on vague ideals. So we can say what we want, because everyone has their own ideas that should not be questioned because there is freedom of expression and … Do I really have to make all these premises?

But it is the one that we all feel compelled to judge, even if we, deep down, are all rotten. It is human.

And by “all of us” I mean us, public (who is also here in the cafe today!) Who spread the word about these games, making the right messages normal, making legitimate or wrong that they perpetuate… Because it’s fine for us . Because that story “gave us emotions”, even if in most cases behind that phrase it is not clear whether ours is true devotion to the work itself or something more rotten underneath.

“Ehm! I respectfully disagree! ”

“Ehm! I respectfully disagree! ”

“What would be rotten in the phrase ‘this story thrilled me?'”

“What would be rotten in the phrase ‘this story thrilled me?'”

“… Vanity, wanting to be understood in any case … Personal comfort.”

“… Vanity, wanting to be understood in any case … Personal comfort.”

But I’m not a judge. I myself, at times, do not understand what leads me to attach myself to a work when I reflect on myself.

So, since we can’t do an examination of conscience on our own…

Let’s see in which types of works we recognize ourselves.

You know, the works that we consider “well made”, projects “to be loved”, stories that “touch the soul’s strings” and many other clichés that bring views to our “video essays”, bring likes to our comments or they just fool people into thinking that we have a deep mindset in the least, even if we are only good at philosophizing…

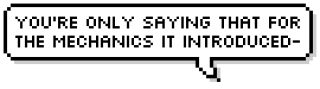

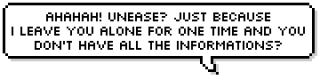

“She started with digs…”

“She started with digs…”

“…”

“…”

“… Every time I wonder if my sister is a masochist …”

“… Every time I wonder if my sister is a masochist …”

“Your support always makes me happy, girls.”

“Your support always makes me happy, girls.”

“So guys, let’s start with the analysis! I will take all your questions and answer peacefully respecting each of your fantastic opinions! ”

“So guys, let’s start with the analysis! I will take all your questions and answer peacefully respecting each of your fantastic opinions! ”

…

“…She lies.”

“…She lies.”

…..

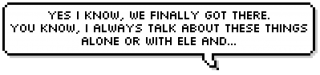

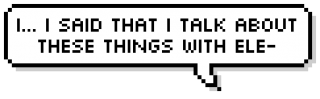

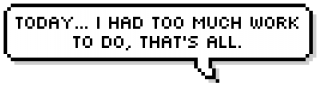

“I would like to speak for a moment to be able to make a premise.”

“I would like to speak for a moment to be able to make a premise.”

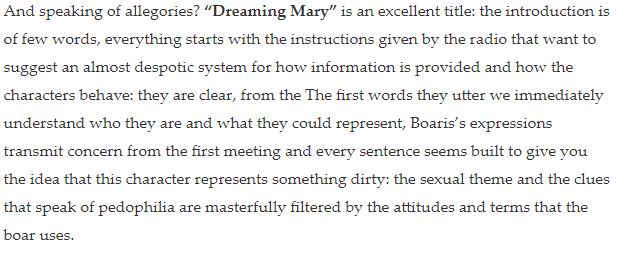

Consider it a small disclaimer, but I really want to clarify that in this type of articles we don’t delve into the titles in their context as we normally do in Back To The Future, but we try to link various titles together around a core theme . This can lead the risk to the perception of a more “conspiracy and / or alarmist” type of article , and it is for this reason that I emphasize here that we are facing a series of personal reflections observing in general the contents that the 2D independent videogame world offers (referring to the titles produced on Rpg Maker specifically) in the narrative field, obviously as is always done in these cases with a good dose of more colorful language for love of entertainment.

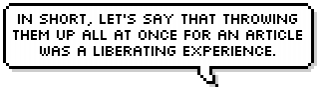

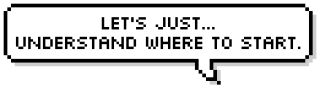

” Okay Ele, after I annoyed you we can proceed. “

” Okay Ele, after I annoyed you we can proceed. “

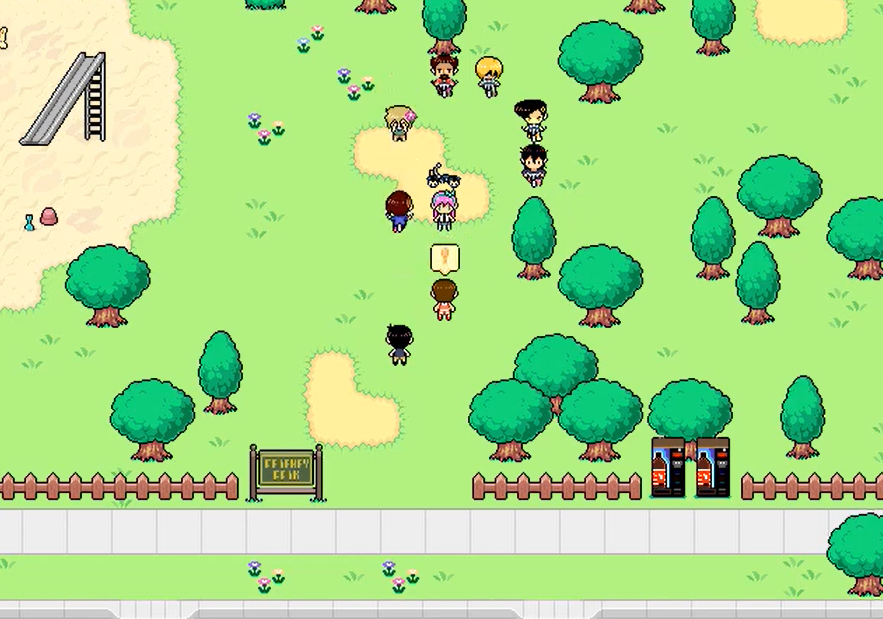

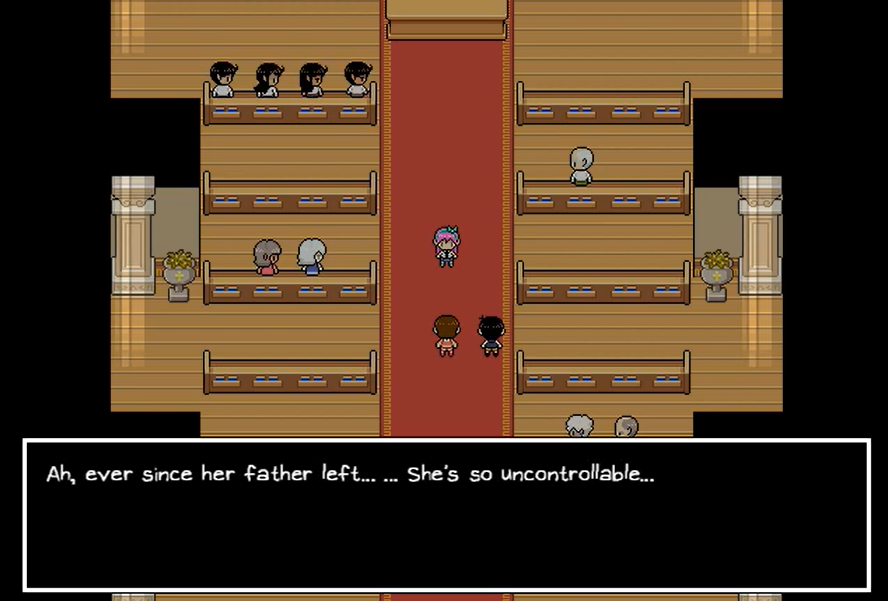

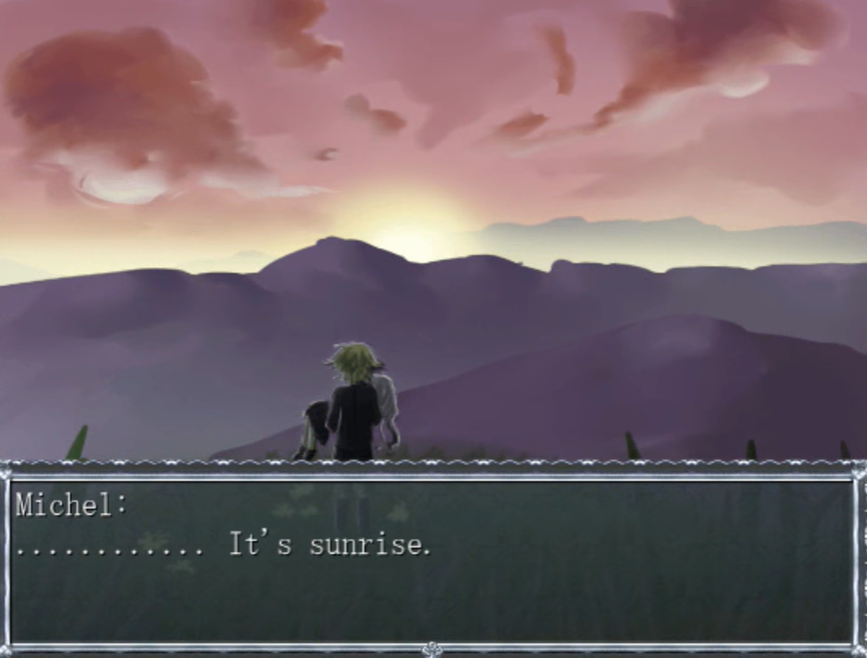

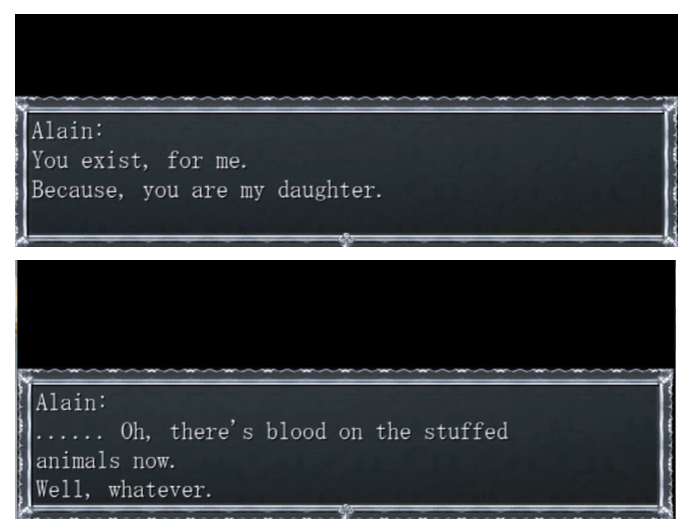

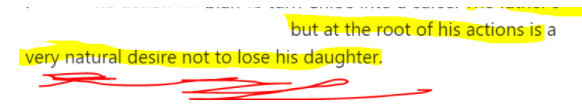

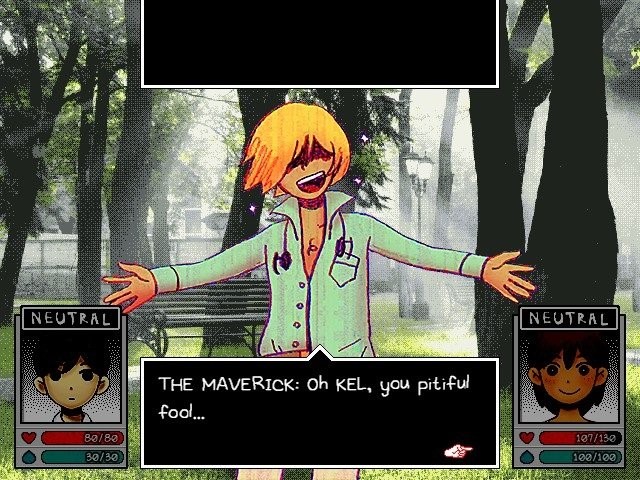

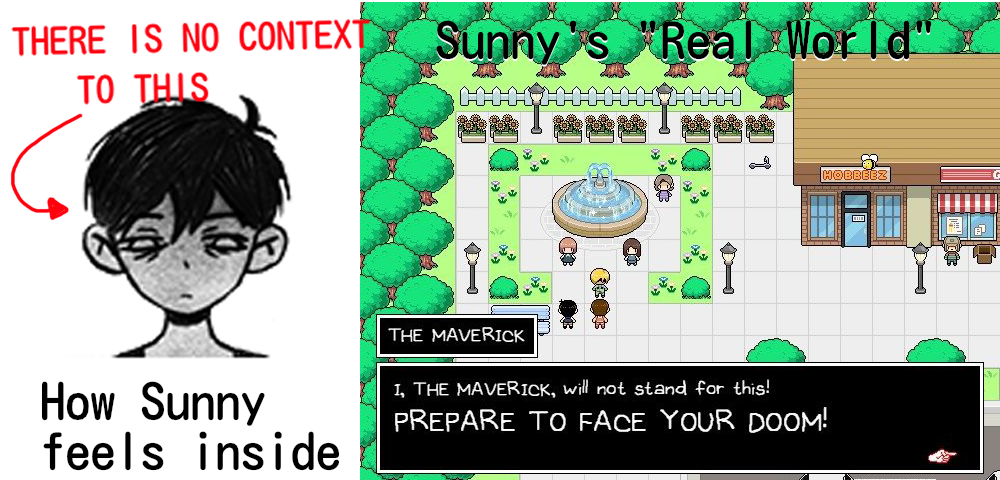

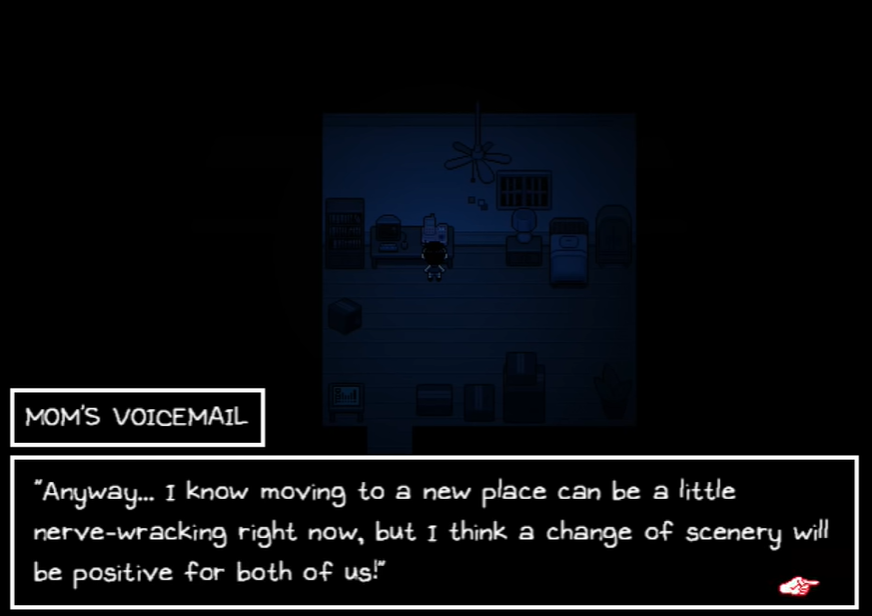

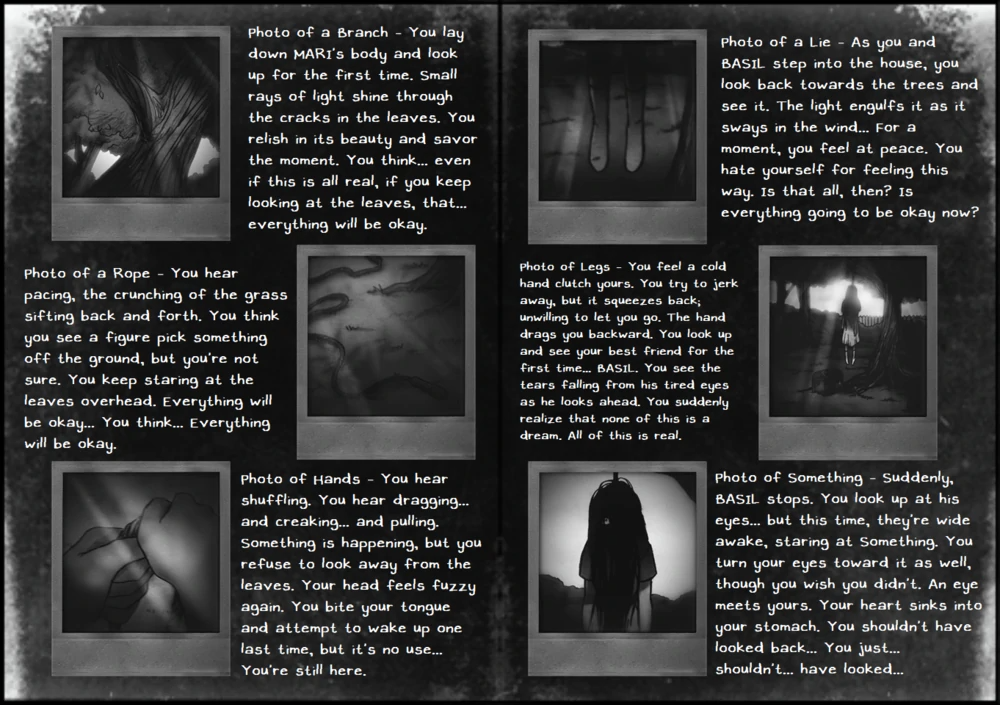

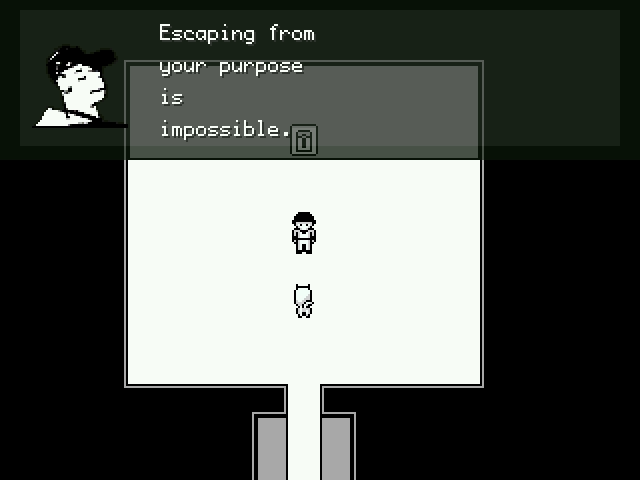

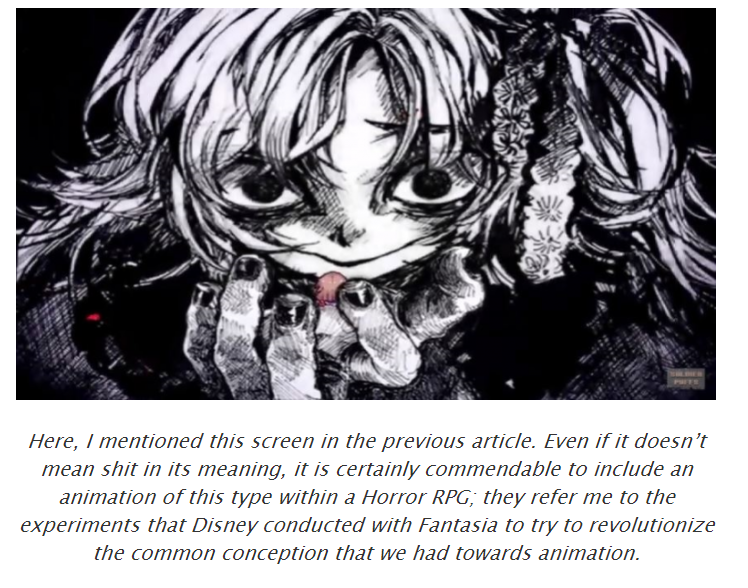

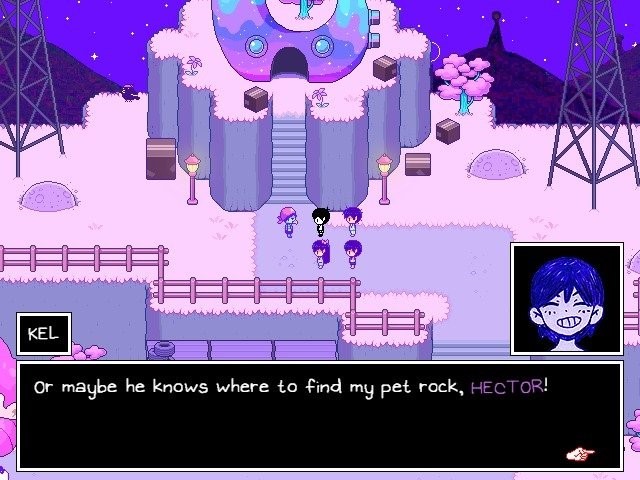

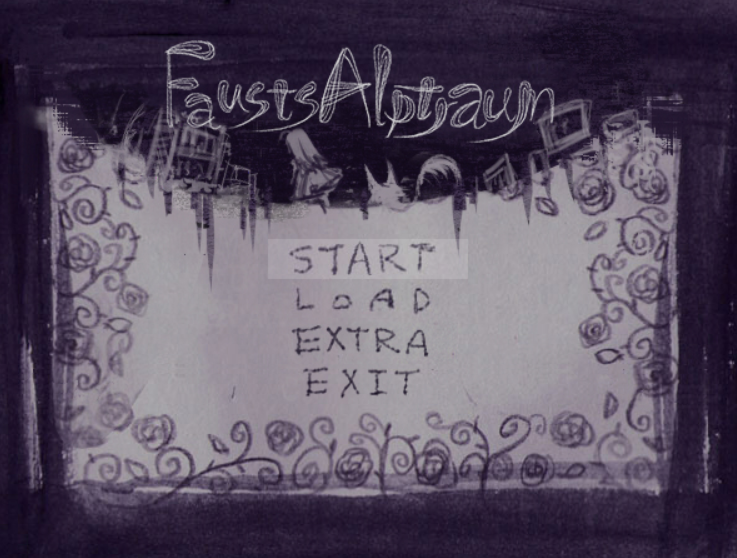

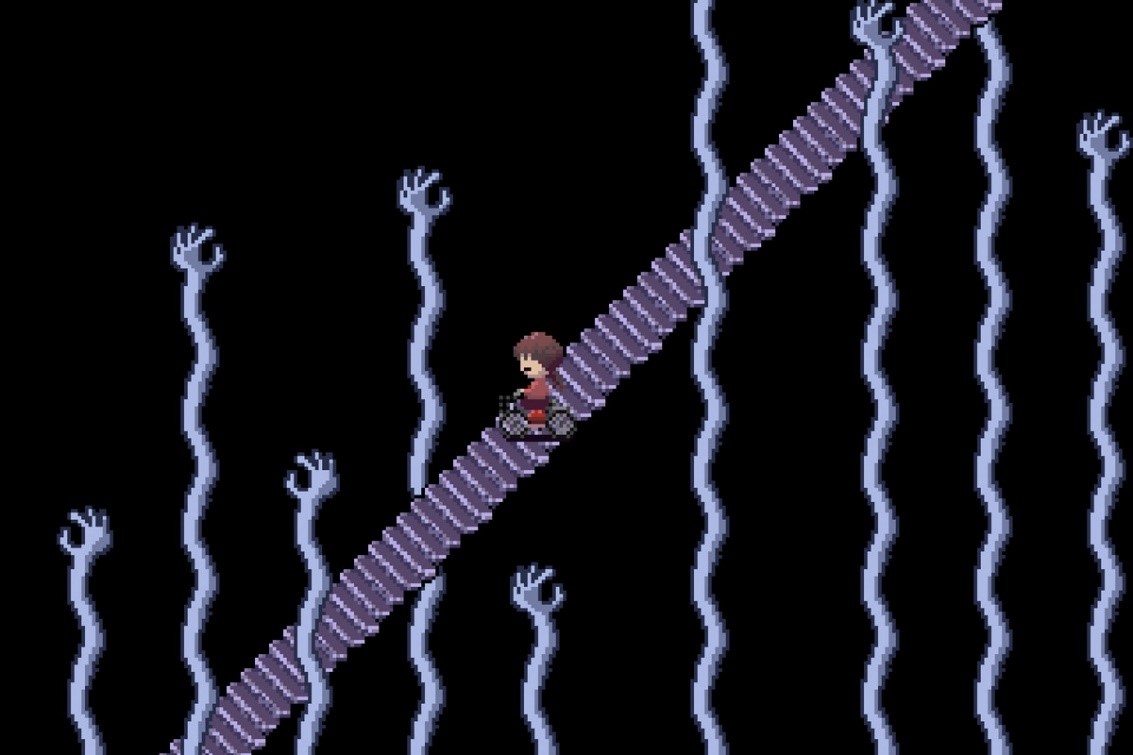

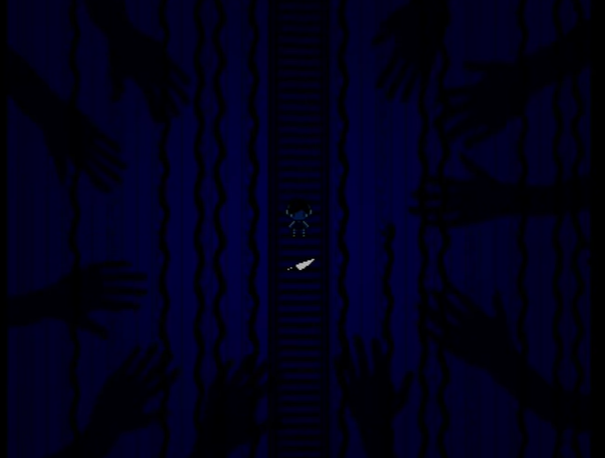

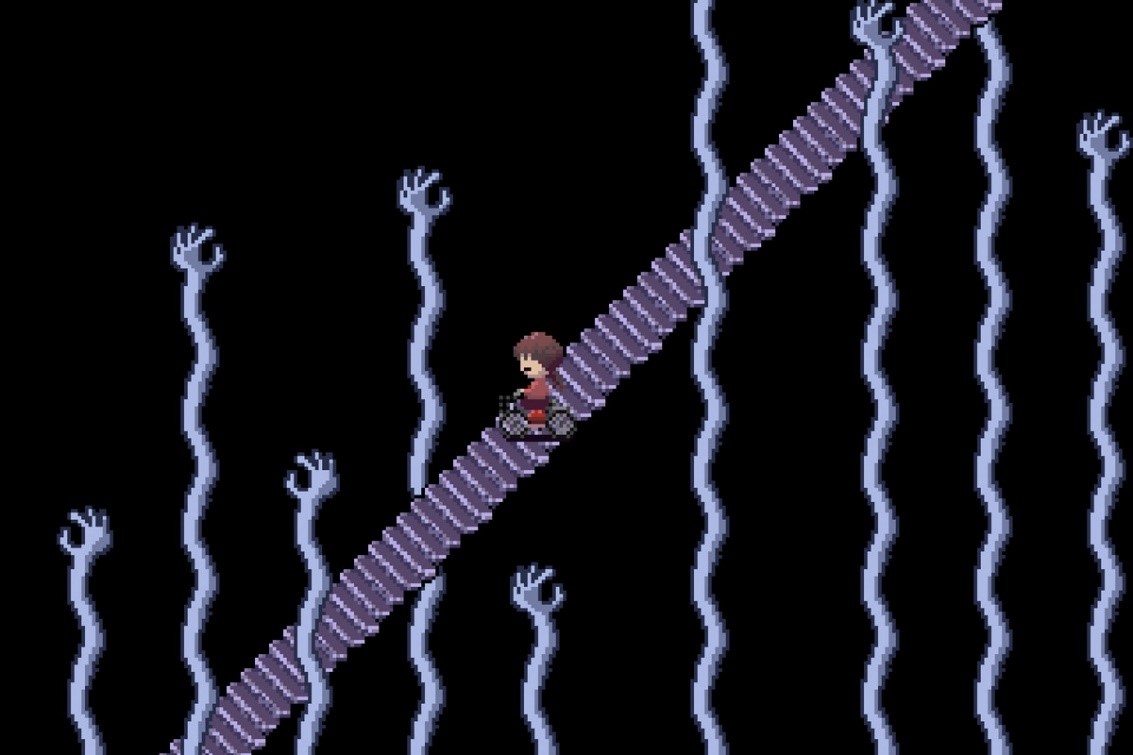

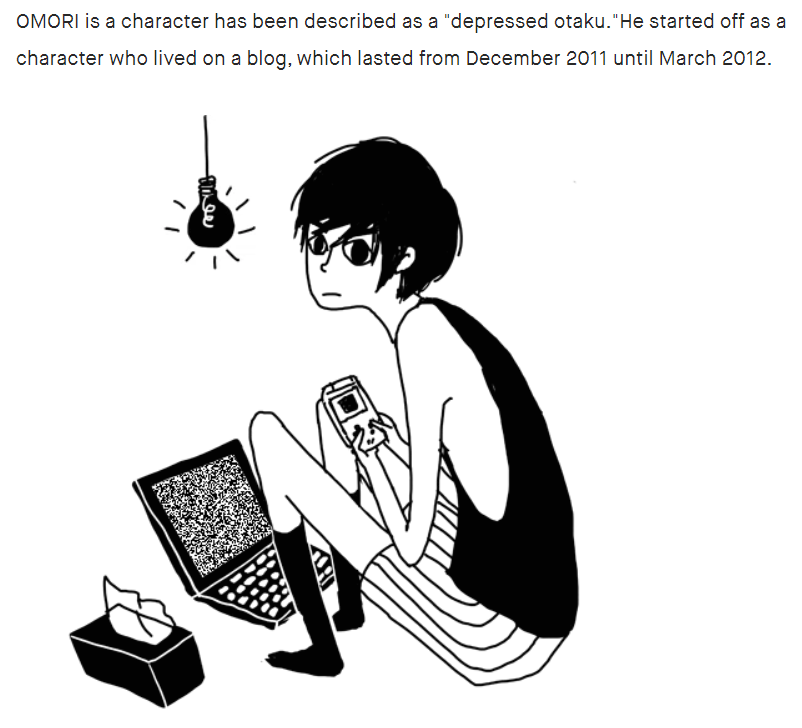

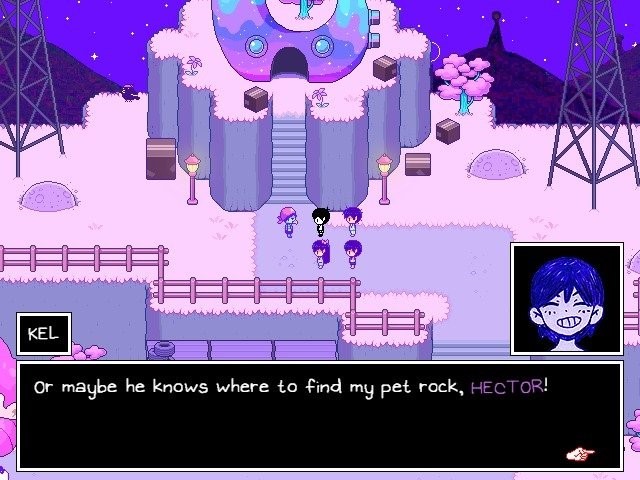

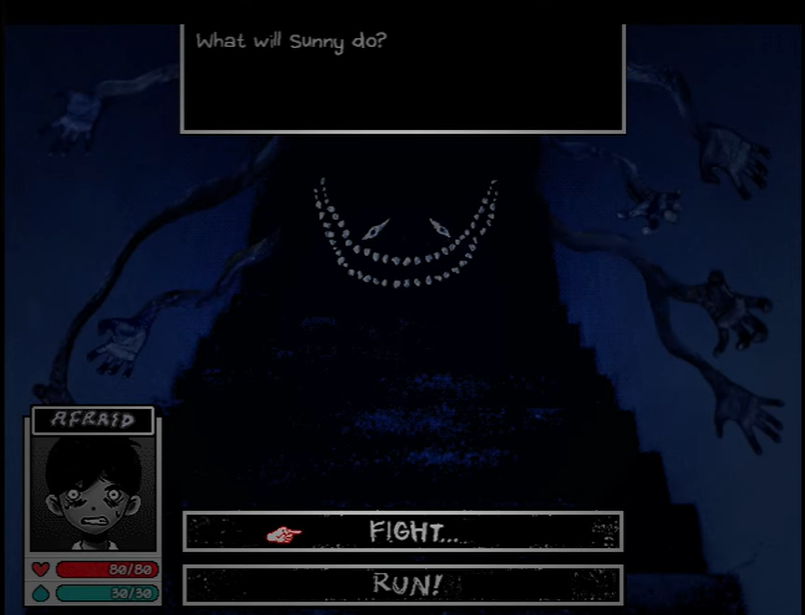

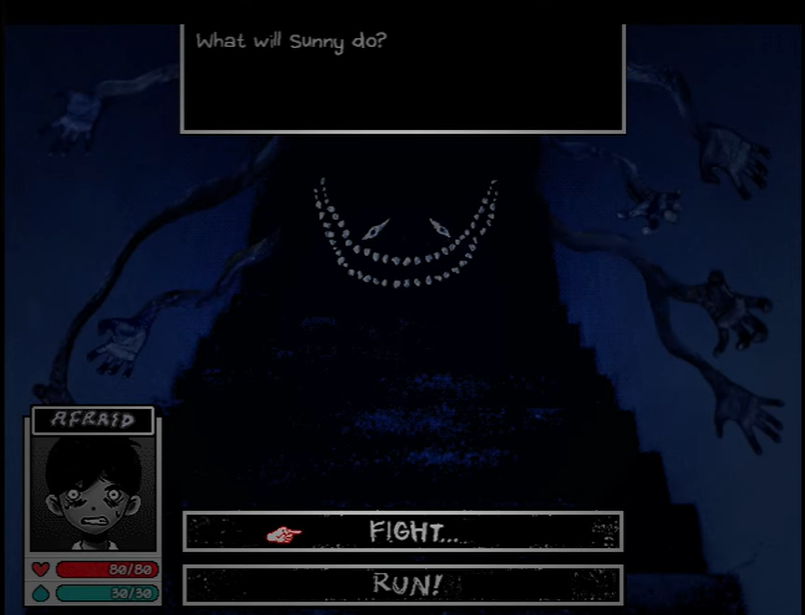

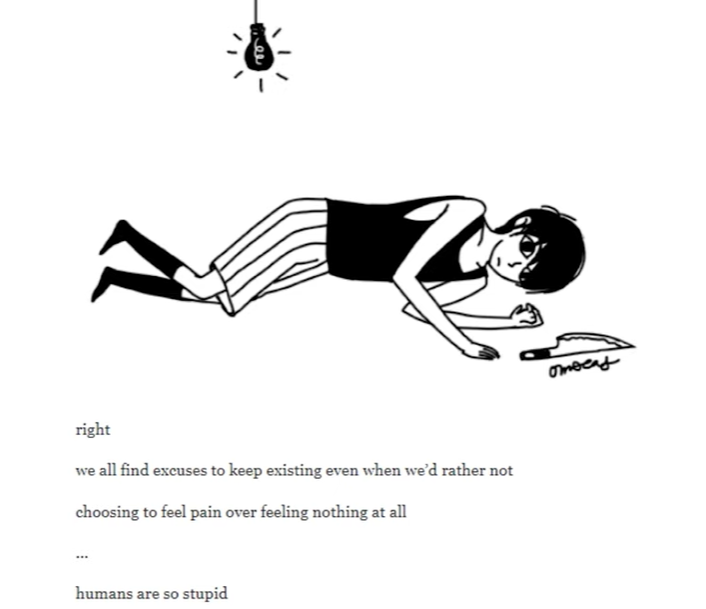

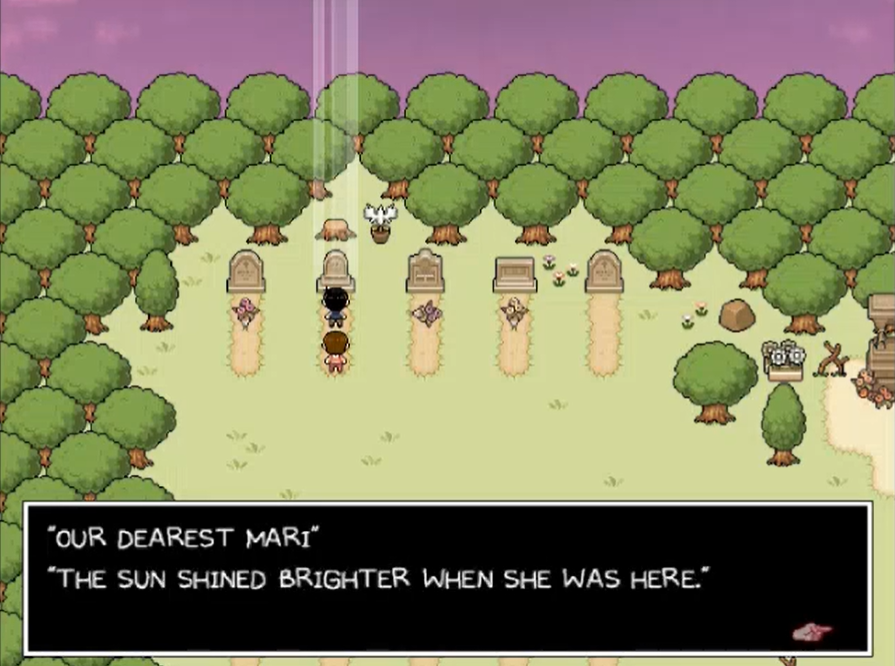

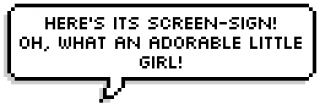

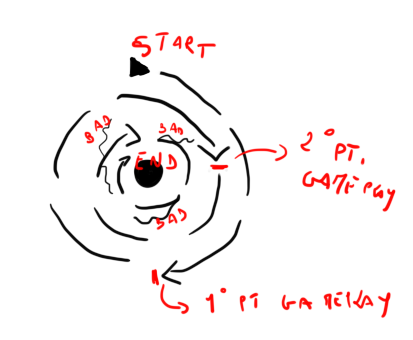

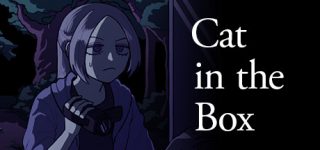

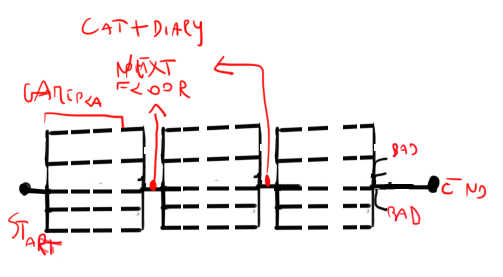

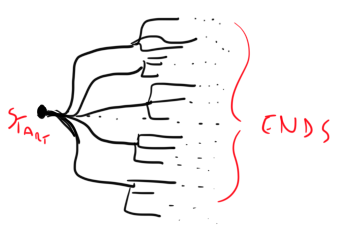

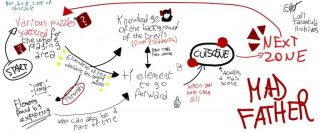

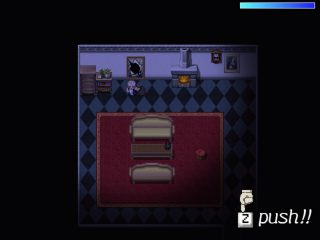

Here, let’s see the last image! A recent Horror RPG (if Omori can be defined as such …)! A rarity!

… And above all, my source of nightmares for a few months.

So, yes, we will talk about much-loved and well-known games …

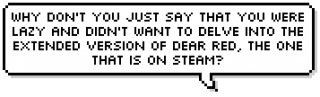

“What a drag! Cloé’s Requiem again?! Haven’t you already made 3 articles about that sh***y game? ”

“What a drag! Cloé’s Requiem again?! Haven’t you already made 3 articles about that sh***y game? ”

“Well, I played it, didn’t I understand what they said in those articles? It’s small stuff, nothing special… ”

“Well, I played it, didn’t I understand what they said in those articles? It’s small stuff, nothing special… ”

“Can we move on to the real interesting debates, please?”

“Can we move on to the real interesting debates, please?”

Okay. We will start from a more general discourse, then.

Okay. We will start from a more general discourse, then.

Part 1 – The “poor victims”

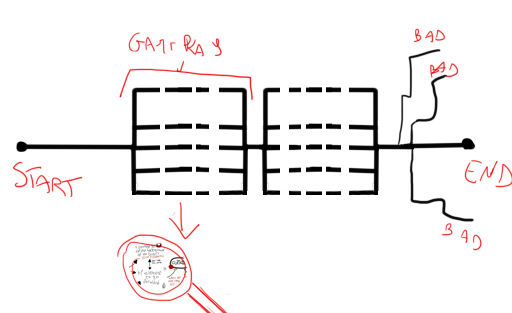

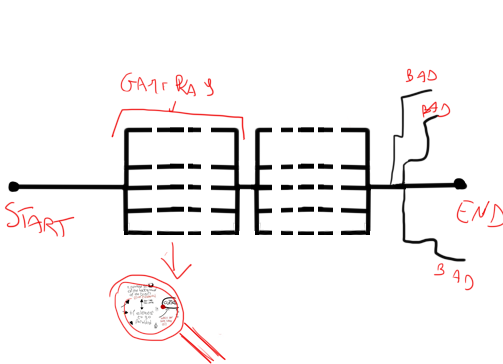

For these first two parts, we will talk about more general themes, and then make the detailed analyzes of the single games clearer.

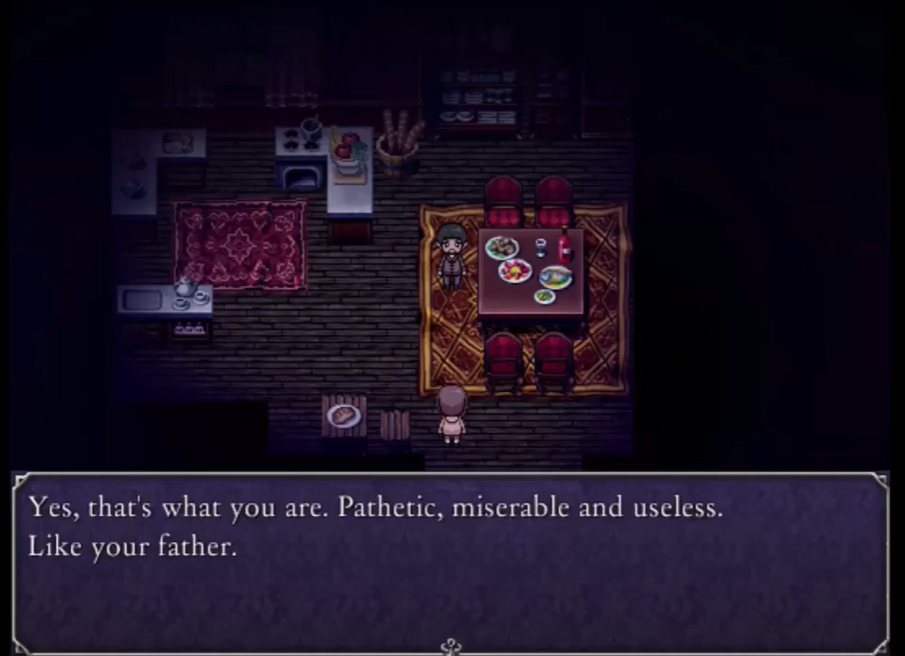

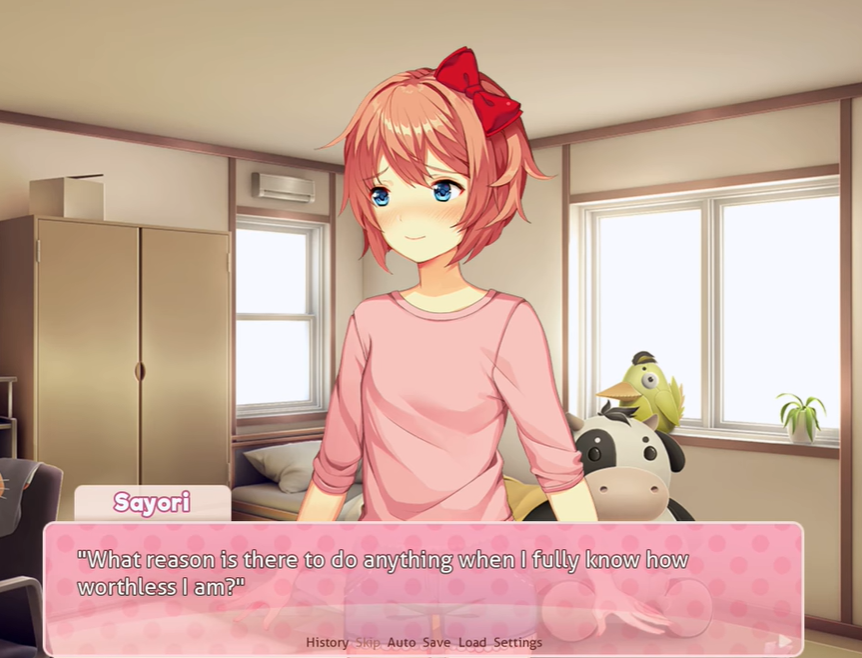

In these three games, “poor victims” are presented each time , people we should in theory become fond of, because of their traumas, bad experiences or emotions that, in theory, should make them more human .

But let’s see, in reality, what we are led to have to defend.

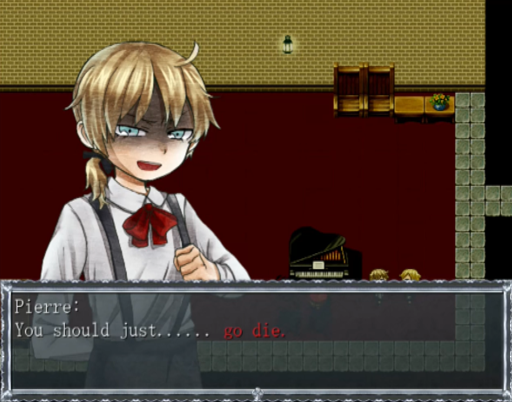

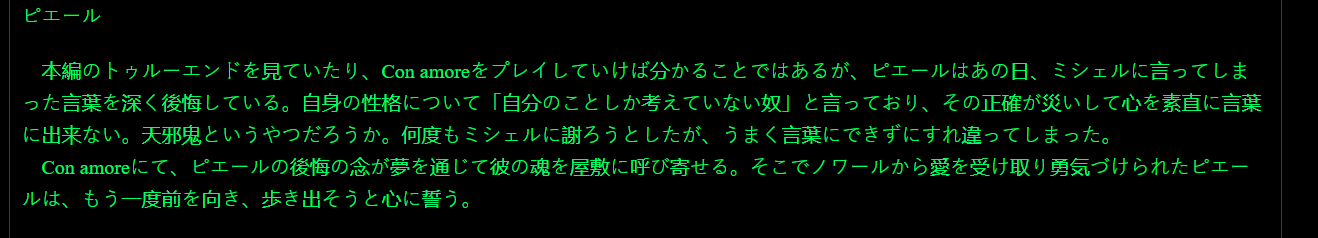

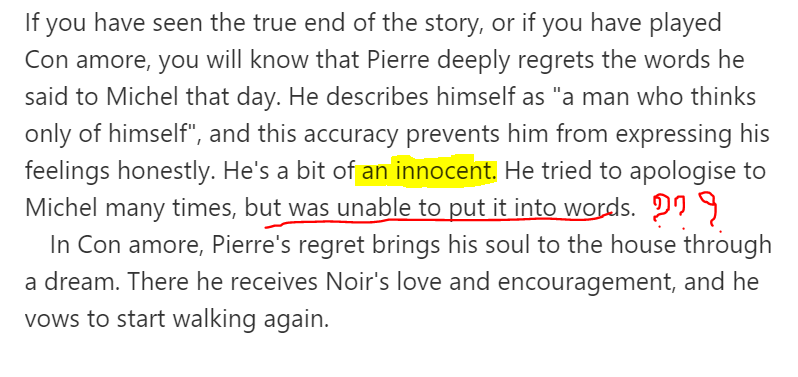

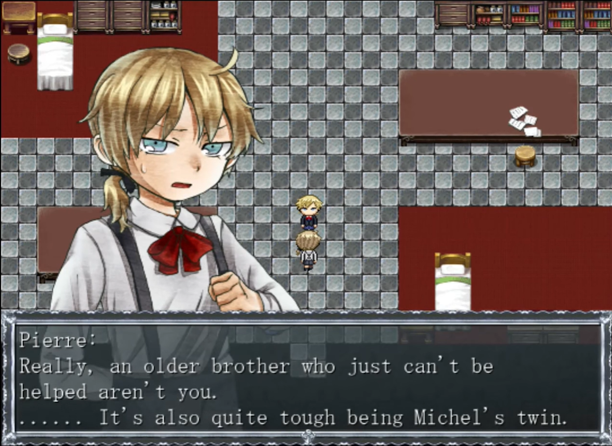

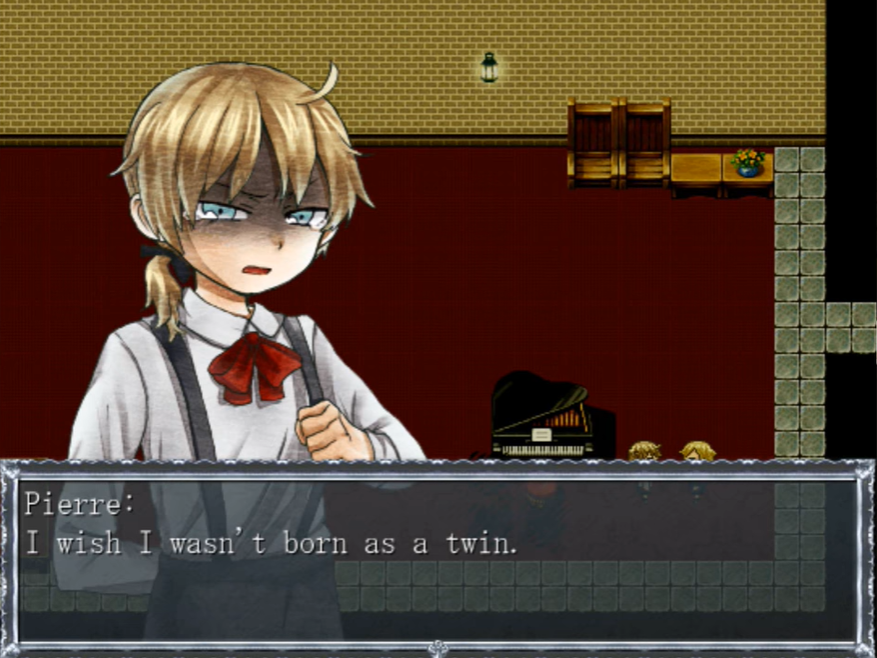

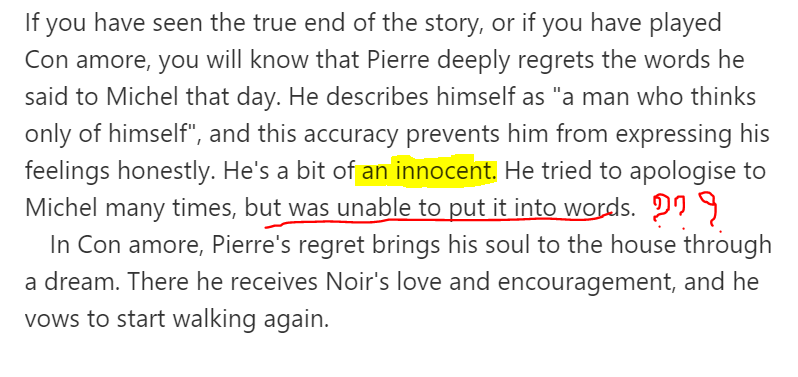

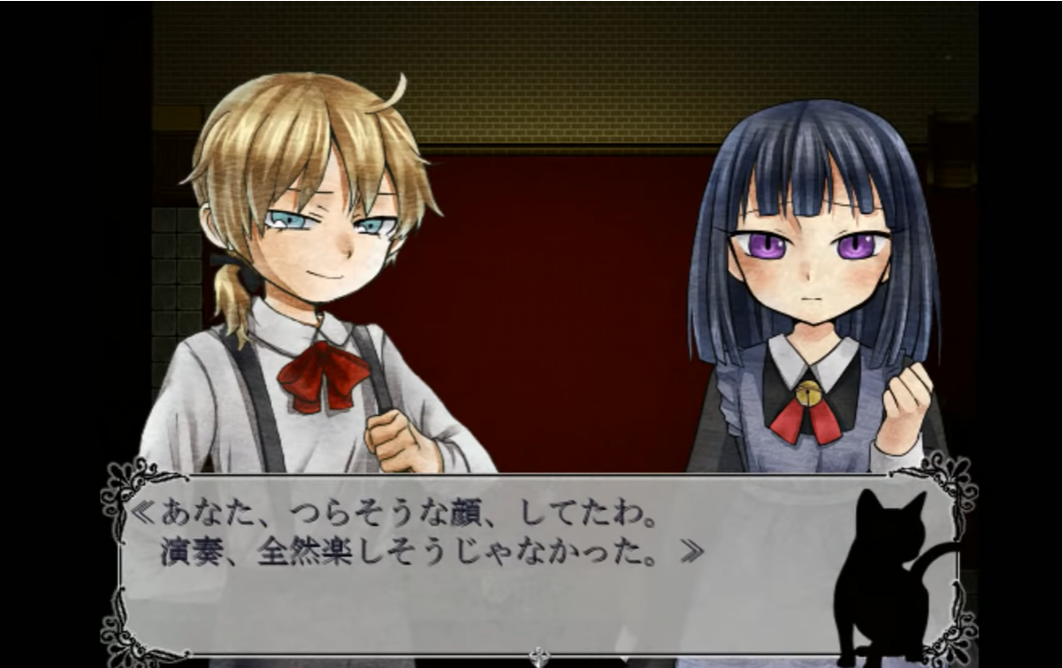

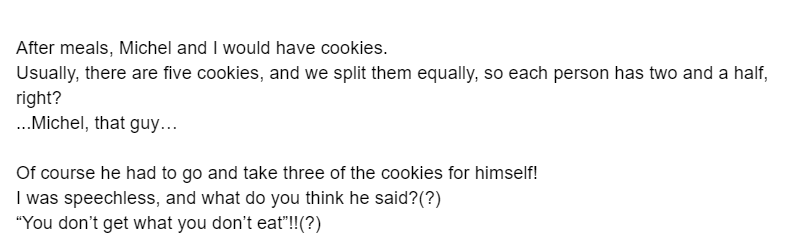

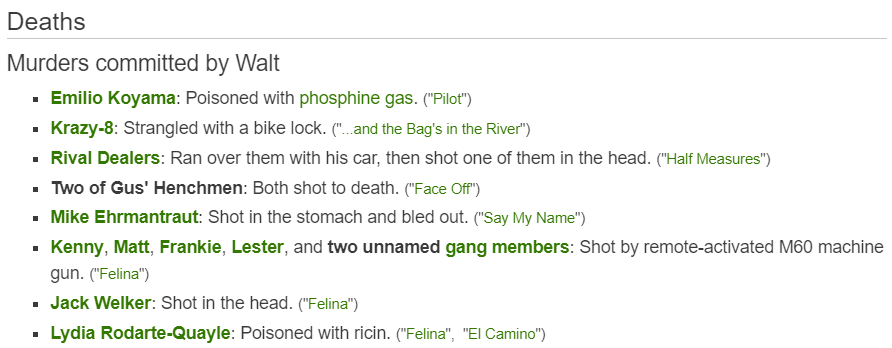

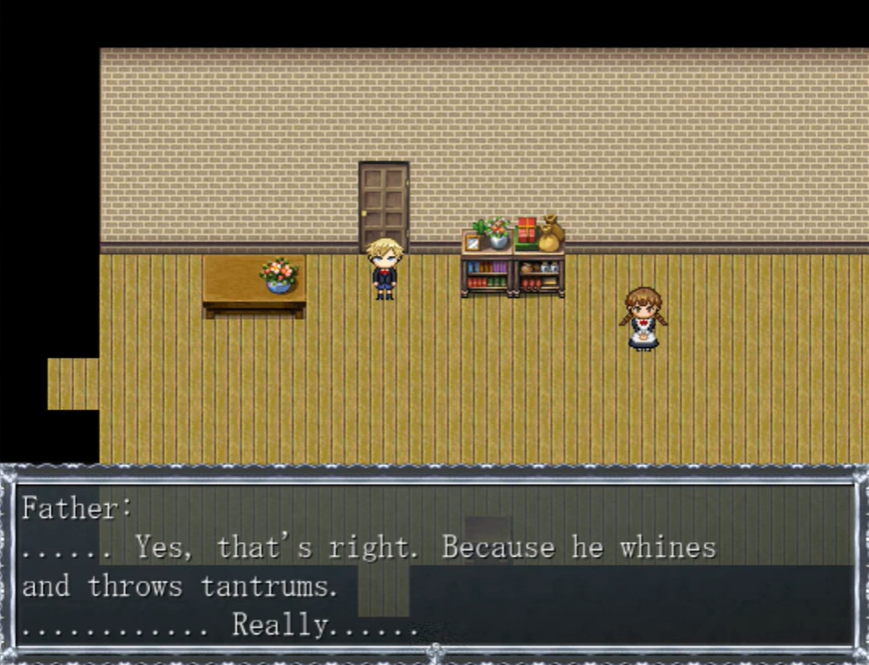

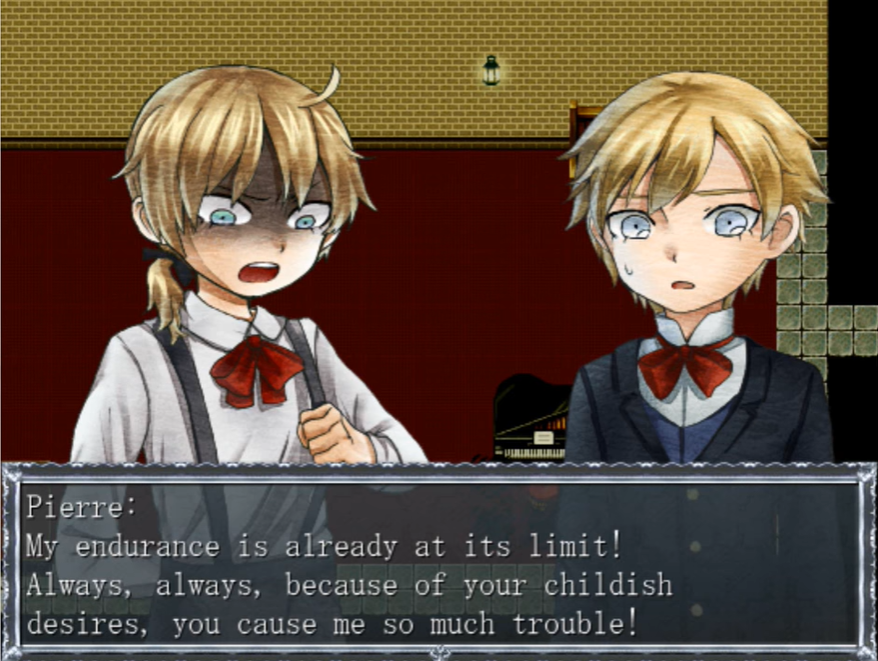

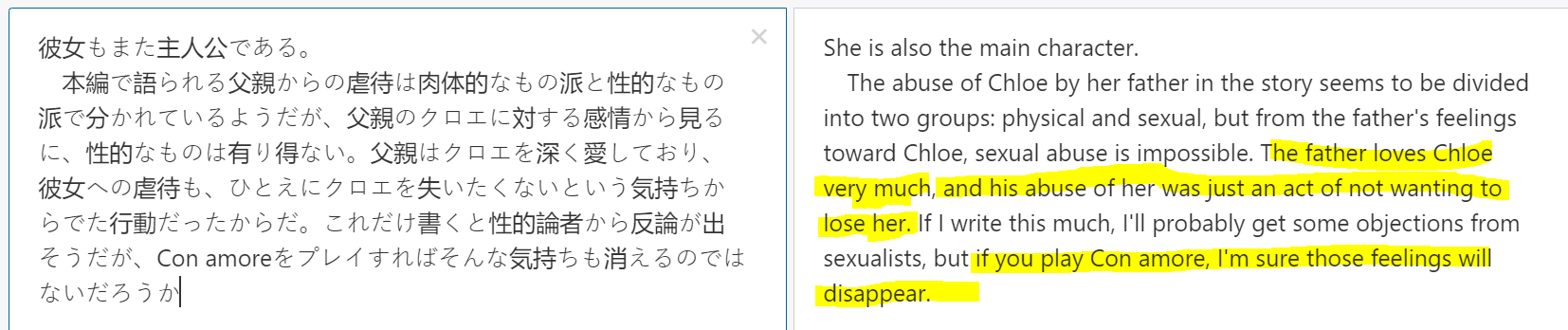

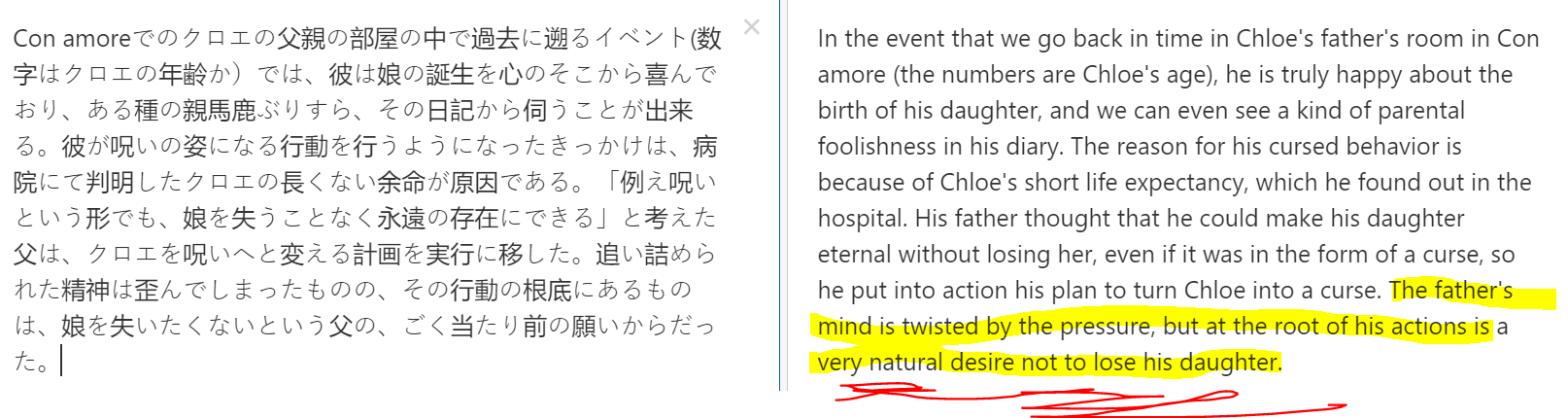

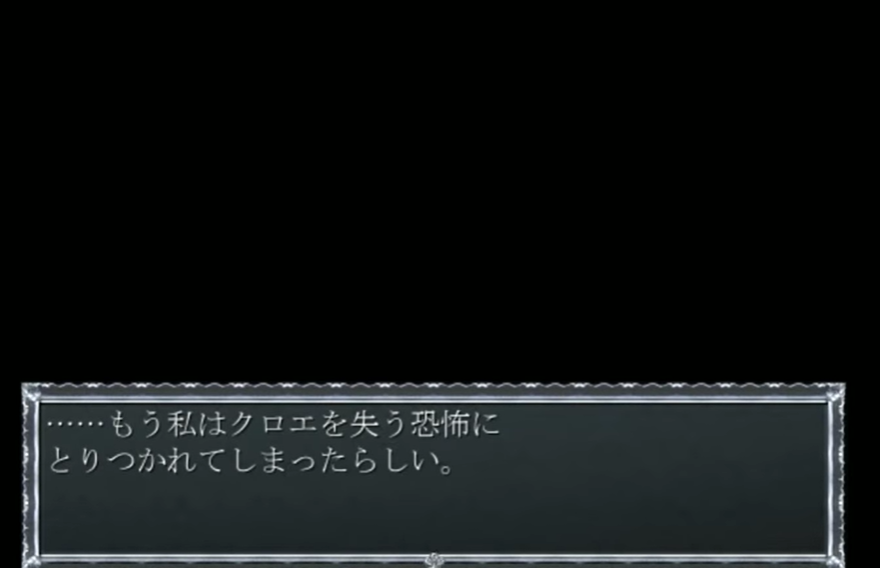

Cloé’s Requiem: Con Amore – “Pierre is a bit innocent”

Before moving on to Con Amore, let’s give a quick overview on the character of Pierre , using our appendix article on the characters of Cloé’s Requiem:

He is presented to us simply as “the twin of the protagonist who is less good at playing”, also blond and with blue eyes.

What immediately catches his eye, always speaking superficially, is the repression of his anger towards his brother.

(…)

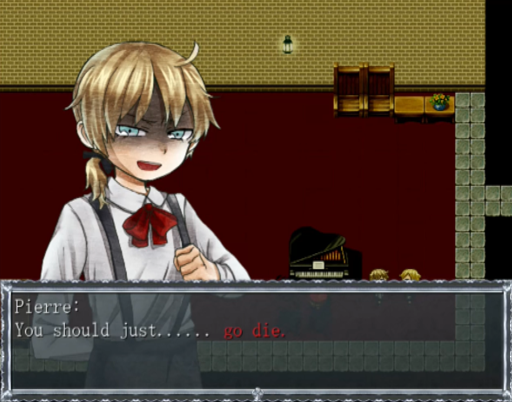

In the eyes of some players, for what he has done and said, Pierre is nothing more than a repressed worm, ready to threaten his brother to kill himself.

Yes, guys, he really said it.

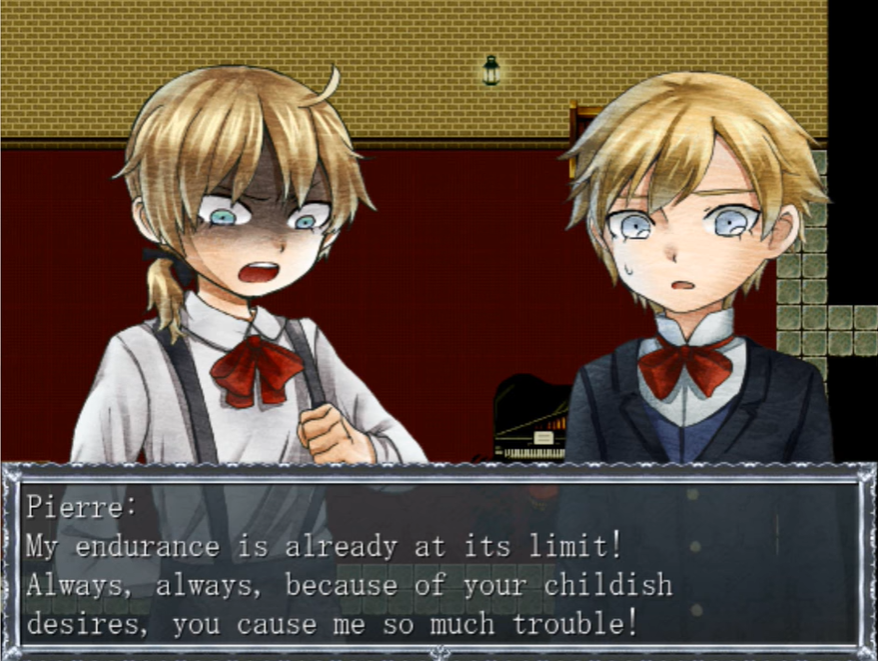

But how was this character, at this point detestable at most, treated in the “extra version” of the game, Con Amore?

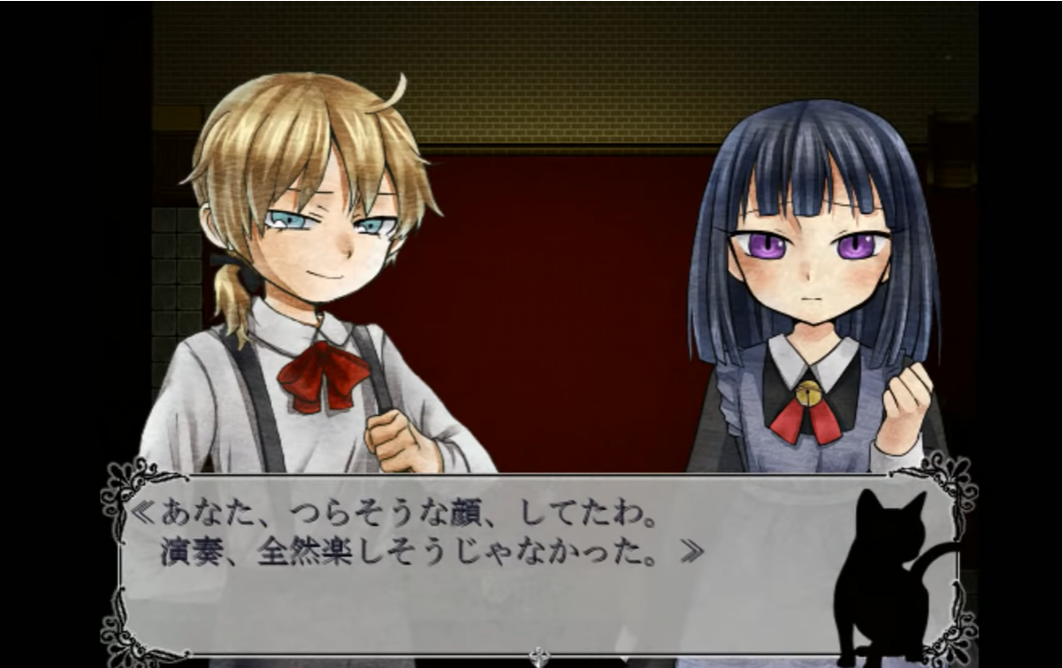

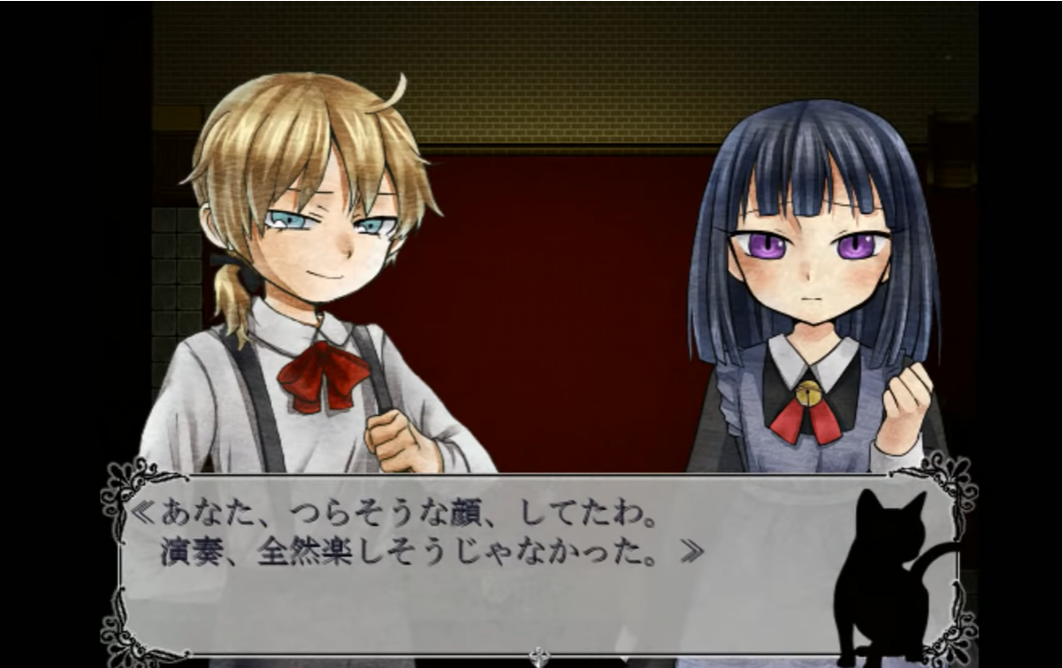

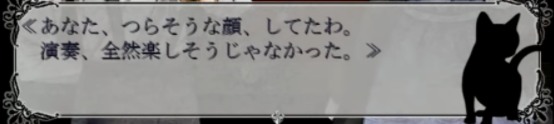

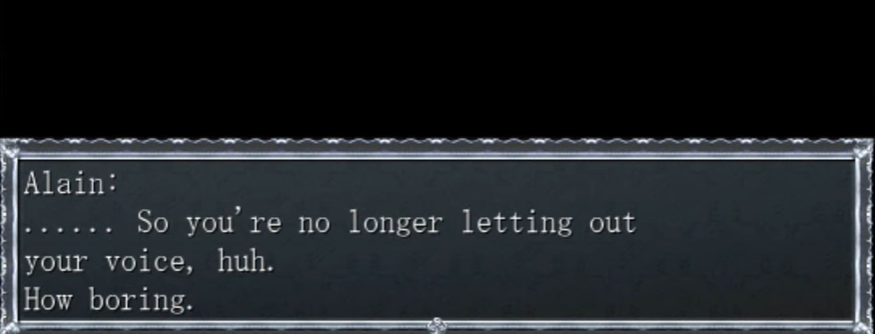

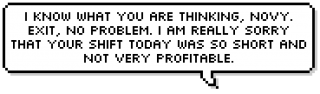

“You had an expression of pain.

The performance didn’t seem funny at all. “

Ok, before I get down to it, if a catgirl gave you a heart attack in this game, she should theoretically be “Noir”, which in the original Cloé’s Requiem is simply a cat and was just a directly contrasting representation. with another cat, Blanc (who is also humanized in Con Amore).

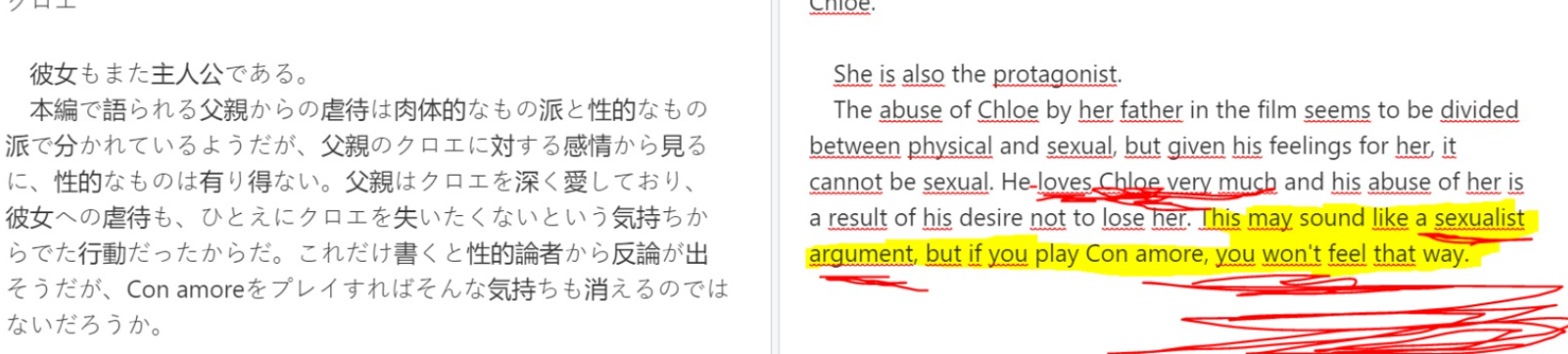

(This is a review of Cloé’s Requiem Con Amore by a Japanese blog )

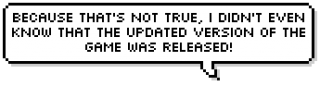

“I have inquired for you and I do not understand where you would like to go. They have eliminated those scenes, you cannot know if he repeated those same words. In original game you are so fond of that he would have apologized to his brother; so if by chance you would like to criticize this version of the game for having focused on a more human side of the character who among other things accuses himself and develops a path of personal growth I do not think it is a fair and deserved criticism. It is not healthy to always find the rotten in everything. ”

“I have inquired for you and I do not understand where you would like to go. They have eliminated those scenes, you cannot know if he repeated those same words. In original game you are so fond of that he would have apologized to his brother; so if by chance you would like to criticize this version of the game for having focused on a more human side of the character who among other things accuses himself and develops a path of personal growth I do not think it is a fair and deserved criticism. It is not healthy to always find the rotten in everything. ”

“Hey, you’re right! It may happen that certain relationships between people become more complicated, don’t you find it very sweet that out of guilt he is no longer able to express his displeasure?”

“Hey, you’re right! It may happen that certain relationships between people become more complicated, don’t you find it very sweet that out of guilt he is no longer able to express his displeasure?”

…

…

… Guys, really?

… Guys, really?

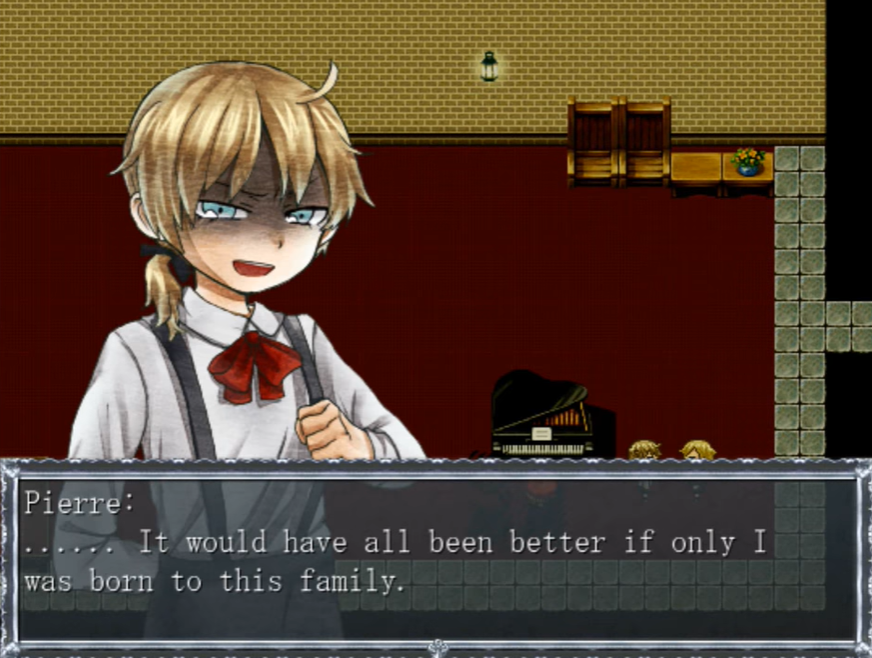

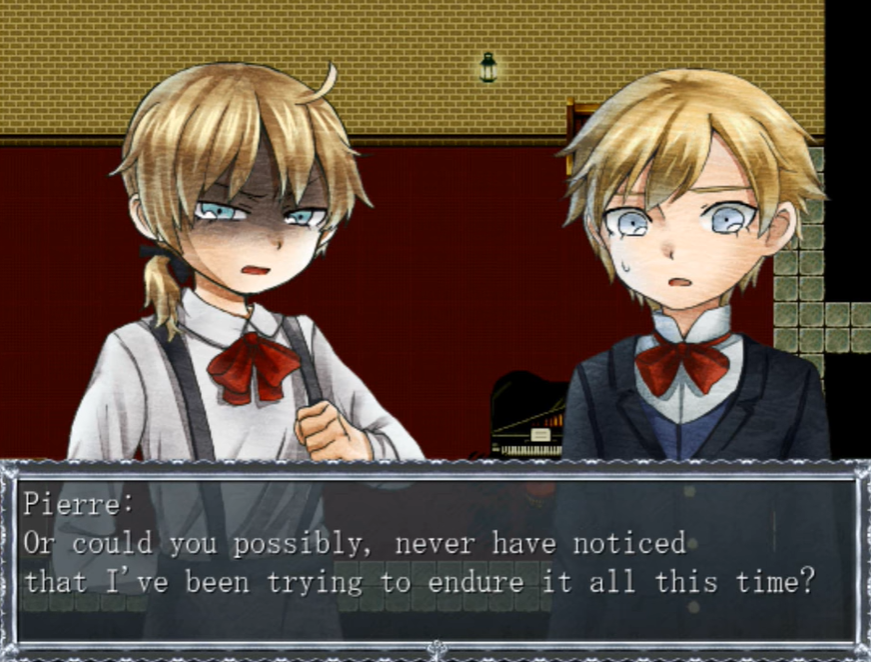

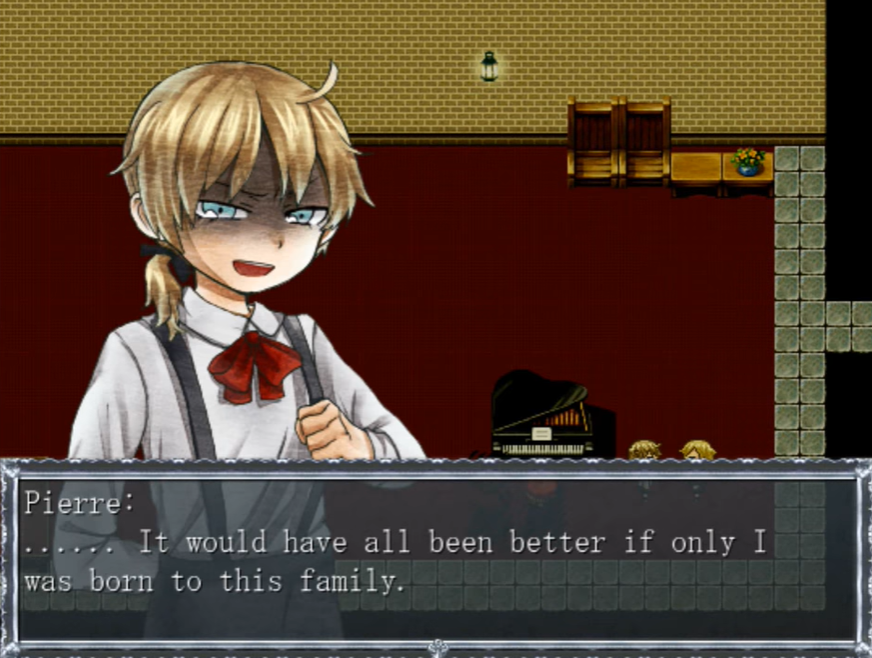

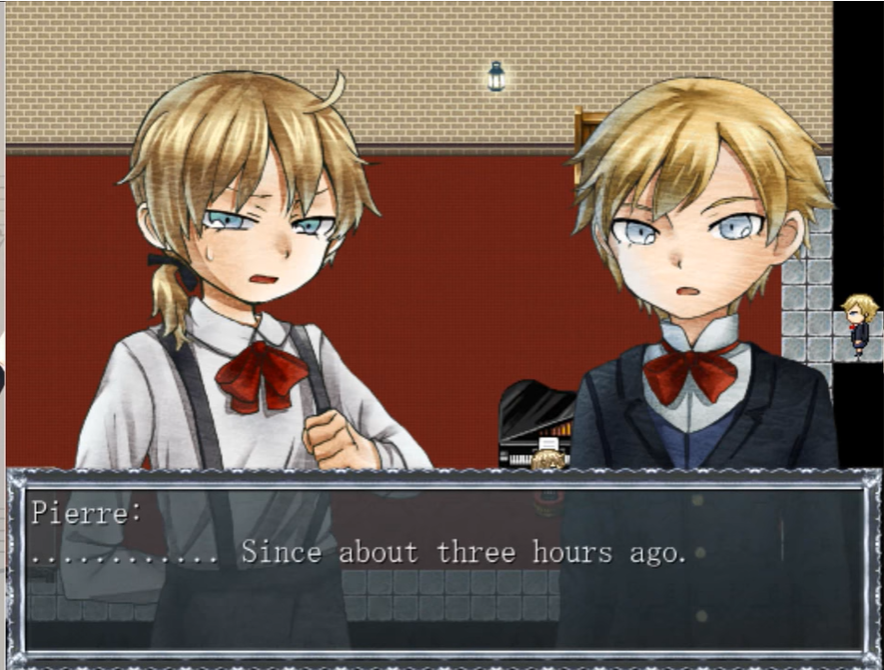

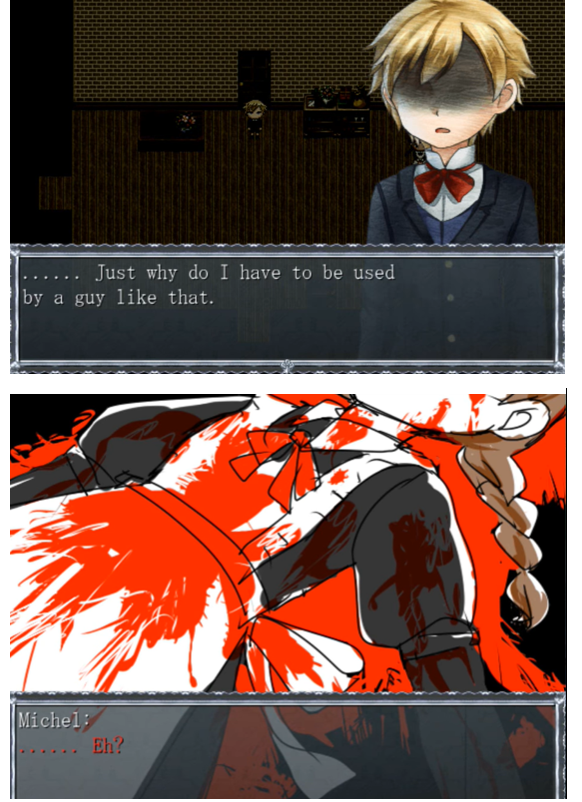

He death threatened his brother…! And since his is a real anger and hatred that he has been repressing for years, also given the cold attitude he has with his brother, along with some digs that can only make you think “what an asshole!”

This is not a simple “misuse of words.” That happens with people you really love. Even before telling him directly to die, he said something cooked and raw, always going to the concept that according to him Michel should not have been born. It’s not something you tell your brother, heck.

Let’s face it clearly: people like this usually never have a problem expressing what they think. A bit of rhetoric as he always did, and even in his ambiguity he would be able to send very clear signals of his emotional state.

And here this subspecies of hole-patching game puts down a quarrel where repressed grudges have been brought out for years …

Like a fight a little bit more heated, but given only by anger and frustration?

“You had an expression of pain.

The performance didn’t seem funny at all. “

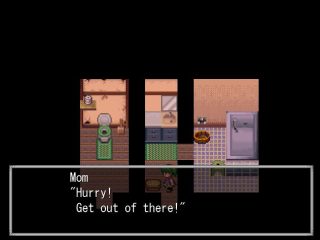

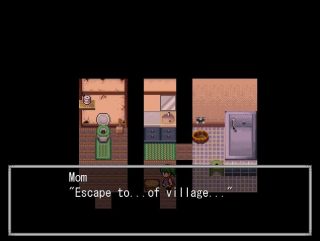

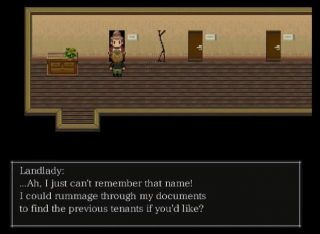

This screenshot, which we showed you earlier, is before the quarrel we mention. It more or less refers to the general condition experienced in the family, because like all the other bad things, as our friend had already anticipated, the fight has been totally censored in this version.

(Review from the Freem website!)

“You had an expression of pain. (…)”

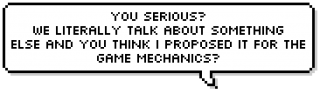

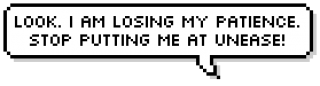

” You think that the frustration, ‘pain’ and how much it may have felt is a valid justification for his ‘outburst’ and to define him as a victim?”

” You think that the frustration, ‘pain’ and how much it may have felt is a valid justification for his ‘outburst’ and to define him as a victim?”

Do you think that “frustration” could be a good excuse for making such a character go from wrong to right by labeling him as a victim?

“… ”

“… ”

You can see then, that to justify this character along with his immorality (such as hatred towards his brother, who is theoretically the wrong person to blame), the strong concepts said in the scene of the fight have been minimized. in Cloé’s Requiem , when those were the very elements that made that scene strong and meaningful .

Pierre’s characterization also suffered from this minimization of the obvious problems that Pierre had.

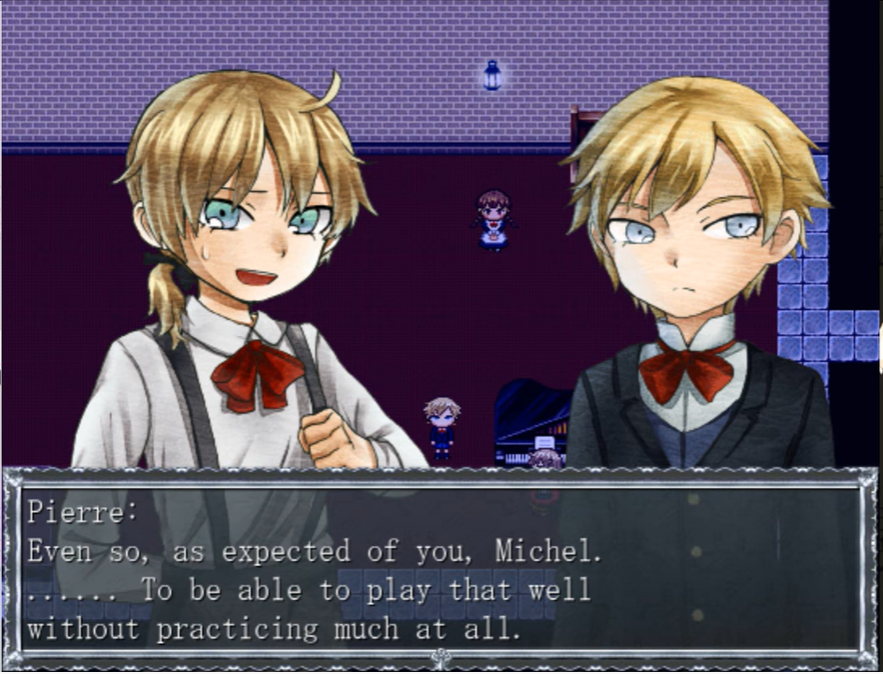

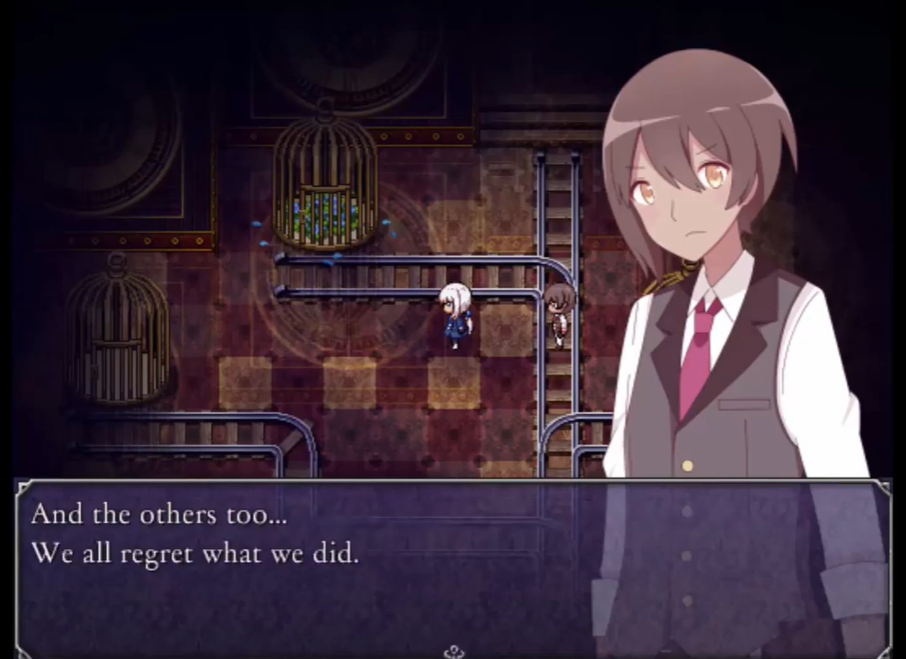

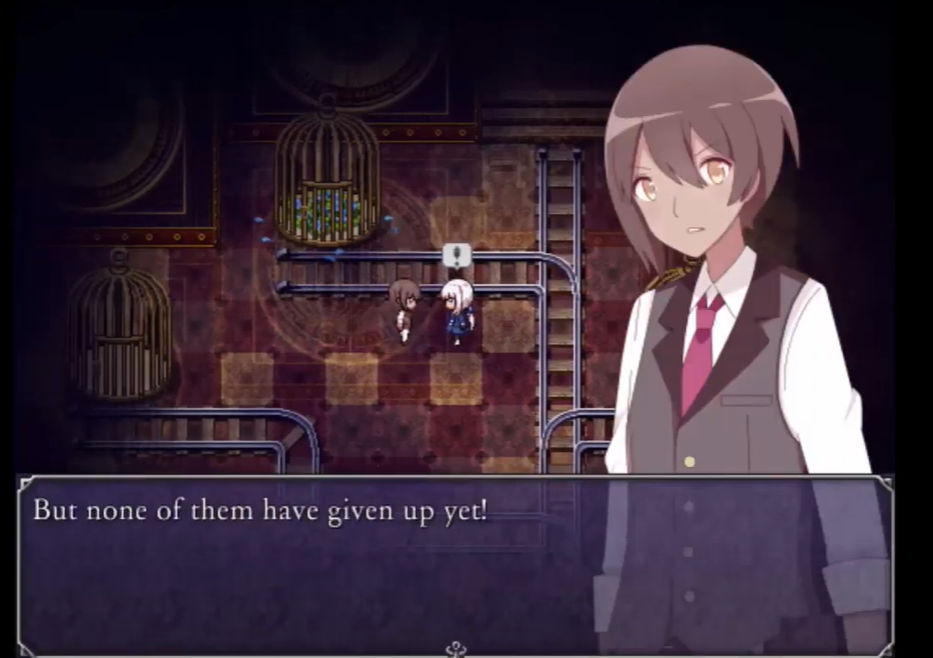

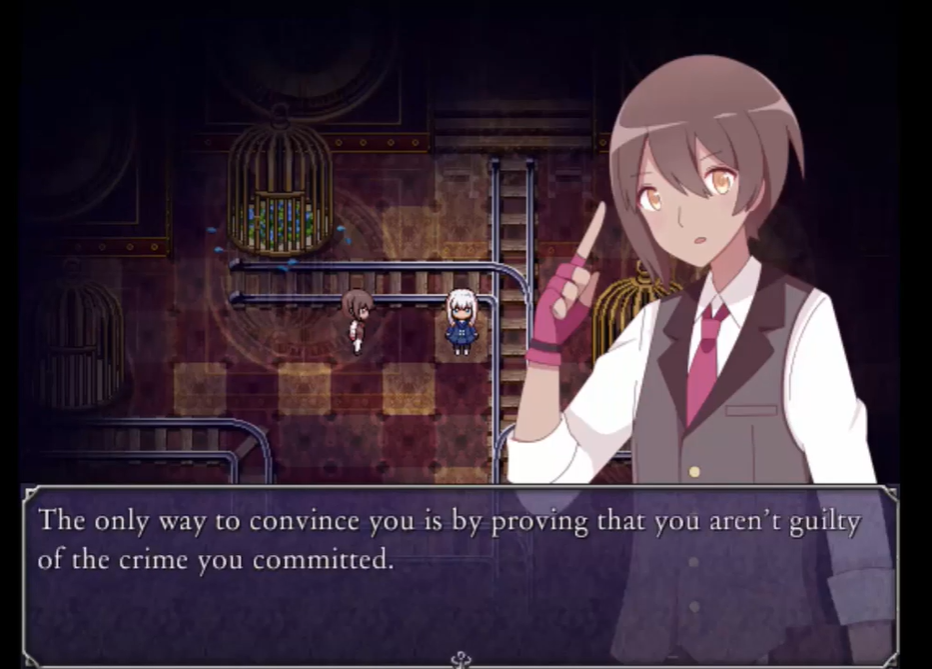

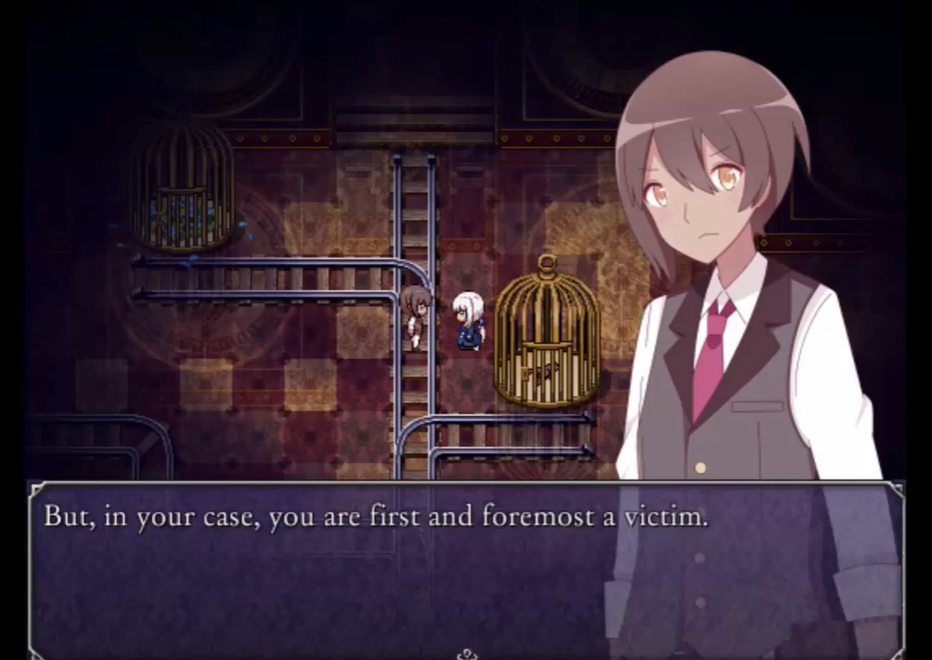

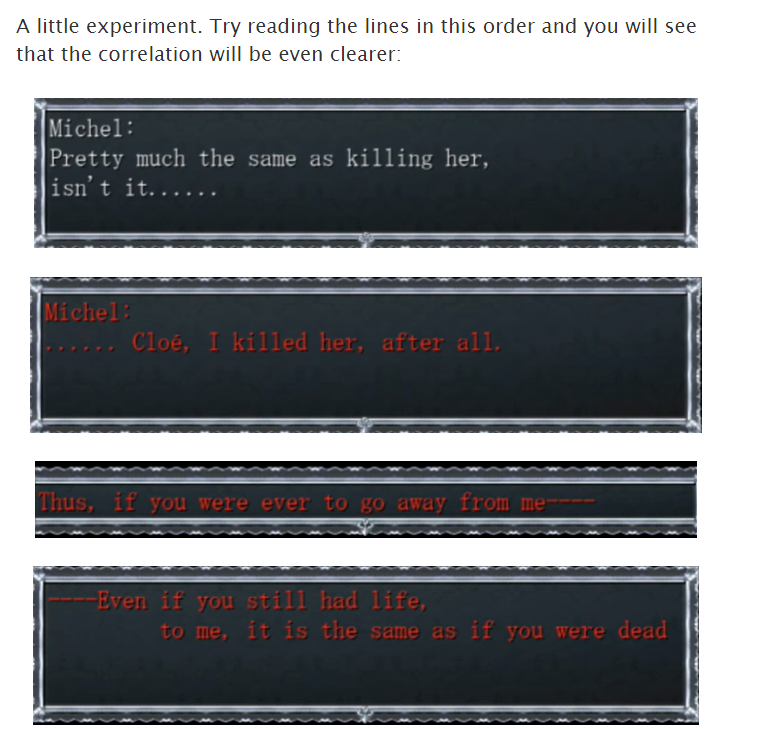

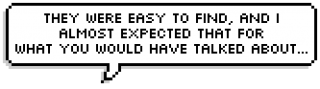

(The context of the next screenshot is that of the image above, although what Pierre says above refers to other events)

(This transcript of a dialogue that happens in the part game is taken directly from the translation of Cloé’s Requiem Con Amore, because in the video from which we took the screenshots this interaction seems to have been skipped … And we cannot take screenshots from us while downloading the game, not knowing Japanese)

Now we explain what they did to this character better: by removing the main characteristic of his personality, namely the attitude devious and false , they shaped him to try in every way to make us perceive him. like a childish kid …

…And the meaning of the sentence you read in the review “he perceives himself as a selfish person” serves to highlight this situation.

Let’s say he has simply become a “poor troubled kid who has yet to understand how the world works and how to openly open up to others”.

So guess what?

“You had an expression of pain. (…)”

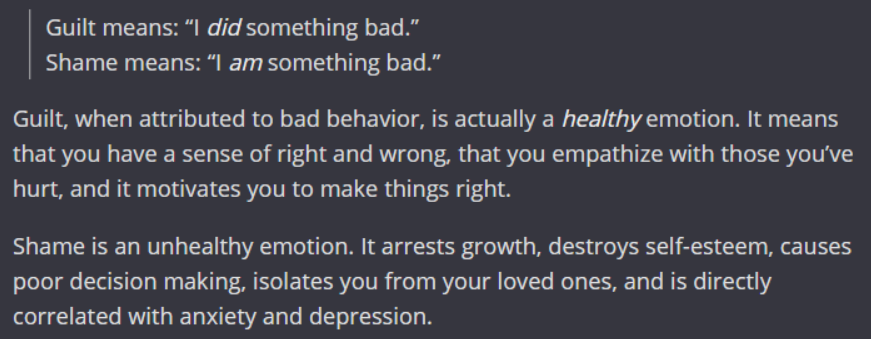

BECOME A VICTIM

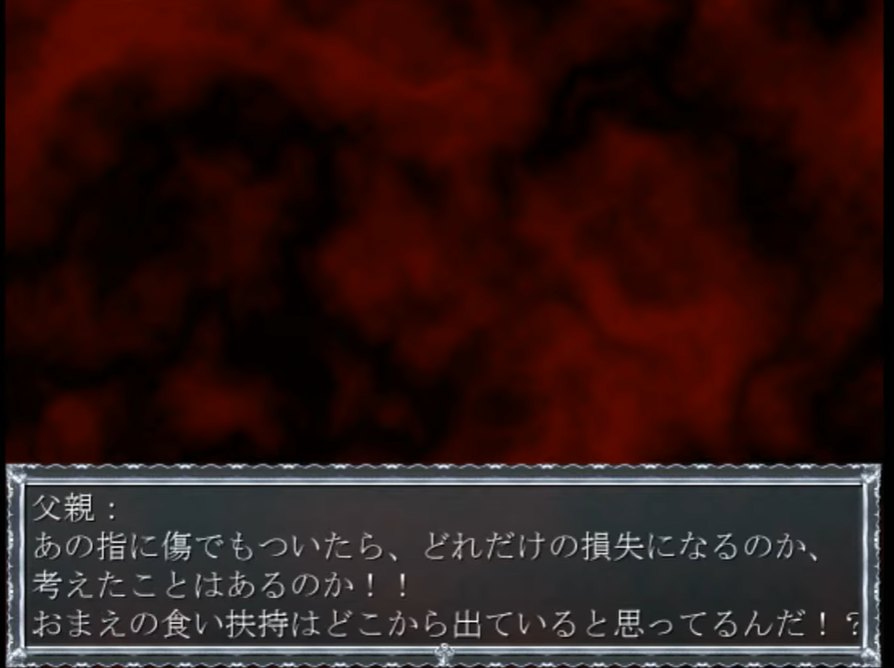

But why do we say this? Because the guilt becomes only of the adults and the insensitive world in which he grew up, for example.

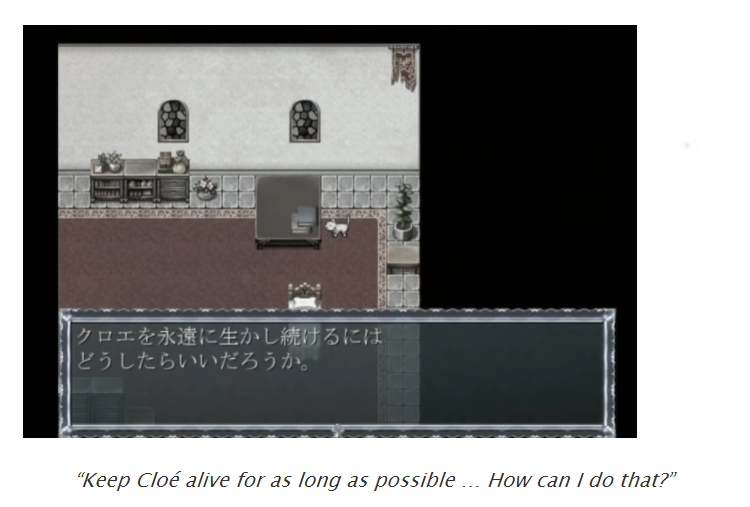

Mr. d’Alembert reproaches Charlotte who doesn’t feel like taking the cat to the mountains, this scene was previously never shown directly and more weight was given to the little girl’s reaction the next day. In this sense the father of the two boys becomes a much more present figure, ready to take on the role of the evil and heartless adult in the most literal sense of the term.

In short, is totally excluded the possibility that he may have now assimilated the typical attitudes of the sick society they wanted to represent and have distanced him from this reality, as a consequence Pierre he took on another personality, as well as another role within the story that could remove him from any uncomfortable situation that he himself had generated in the original situation .

The cause of this:

It becomes this:

That is “ a single moment of weakness” given by momentary frustration, in reality is a good person , is a person to be pitied by this or to be sorry for.

“If I apologize to Michel, could it sound like it used to be?”

“Yes, sure, I’m sure!”

We explain one thing to you.

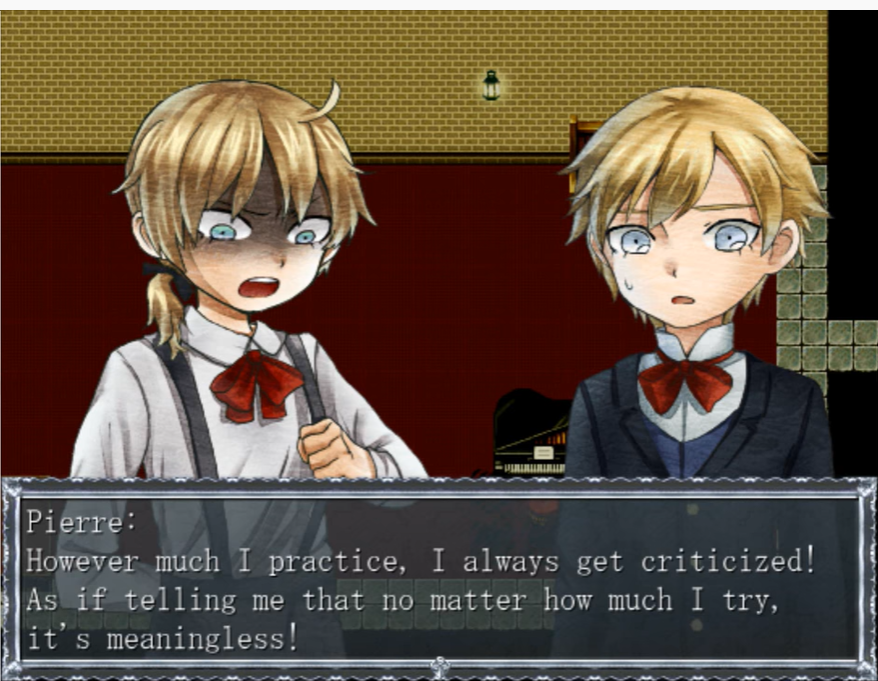

This change of course with all its relative repentance, the beating of the “infantile and selfish but good-hearted boy who cannot express himself” makes absolutely no sense when you think of the restrictive family and social context in which he was evidently found in the original game: let’s say that the guilt of “selfishness” was the last thing that was thought of in the most concrete terms. Those who could afford it led the reins and deserved his accolades; those who could not dictate the law were limited to being an instrument in the hands of the strongest. Thus, being “a lesser tool” Pierre was working towards a higher status. He practiced for his father’s recognition, simply applied the morality of hard work and “meritocracy” , in his perception of things the ideas he manifested during the game (including vent) they were all legitimate ; is not that he “suffered and therefore committed the bullshit”. Do you know when he started wanting to apologize? When the father died, that is when the object of the competition with his brother fell. Because, for the rest, he had ONE YEAR to apologize – and they live in the same house !! – and he absolutely didn’t give a shit.

(As always, we would like to underline the disturbing super sudden expressive change)

… AND THEN, from all the repressing and stacking emotions, the final rant is here.

I would like to point out that these words cannot be uttered by a person who doesn’t really cultivate these negative feelings . The focus of the matter is not that he is a childish person per se and that he “always wants everything for himself”, that was never the real problem. It can certainly be a way of seeing the character, a change of perspective that the authors have had towards him, but the point is that in reality, Pierre’s reasoning is correct, they make sense.

The change seems really imperceptible at first friction, but the reason we are talking about it here and we care so much is that everything has been done to de-empower the character of his faults making him essentially “harmless. “and absolutely redeemable at 360 degrees.

Here, THIS is what you might describe the spoiled and harmless child , just know that it has nothing to do with the original !

… You can see for yourself that the problems he complains about are quite different.

We want to remind you how in the previous intentions we wanted to insist more on infantility, instead, of Michel: he is the character who ultimately had to face this issue, and the game does not failed to show you the negative side of the argument!

The result of all these changes in Con Amore, the proof that the approach in the way of seeing his attitudes has totally changed can be found in the doing this has minimized any possibility of conflict with other characters.

Let’s see for example a difference: observe how he treats Charlotte as a subject here, where as the nice guy he is, scolds her because he cares: “You will fall! Be careful!” and so on …

… And how you treat it here. This expression speaks for itself.

In short, Charlotte was totally right after all!

But in the next case we will deal with a much worse thing, that is the total pathetism, given by the justification of an estabilished bully.

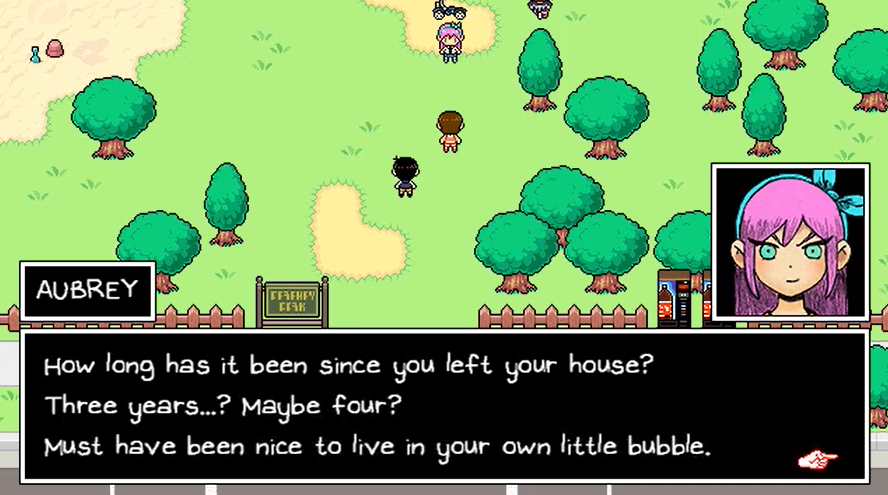

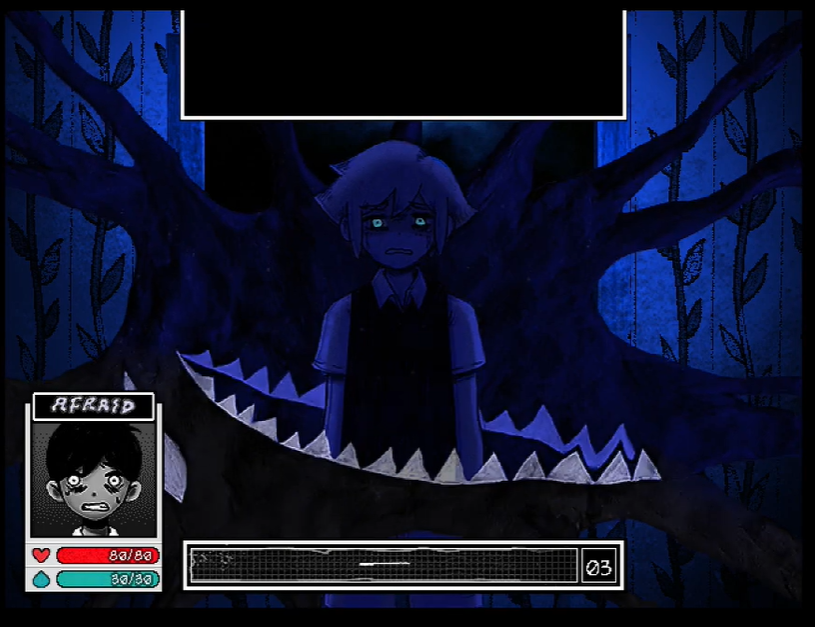

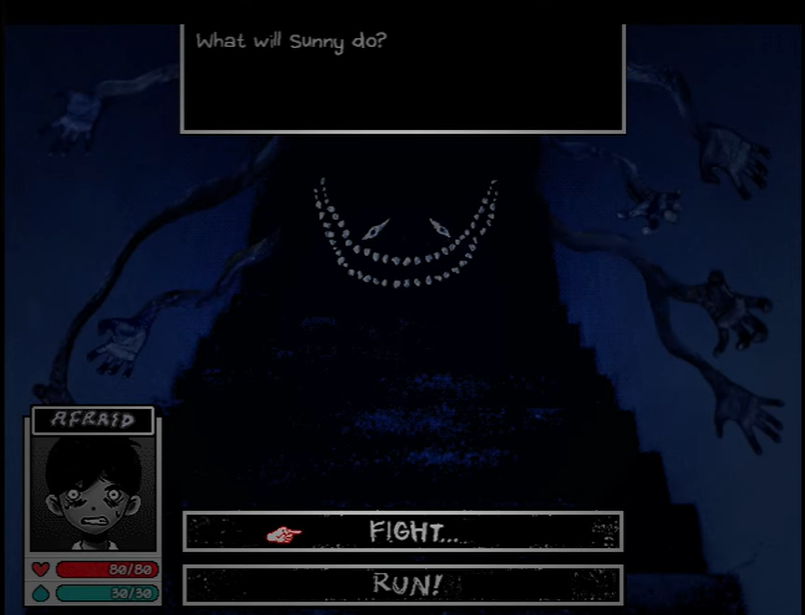

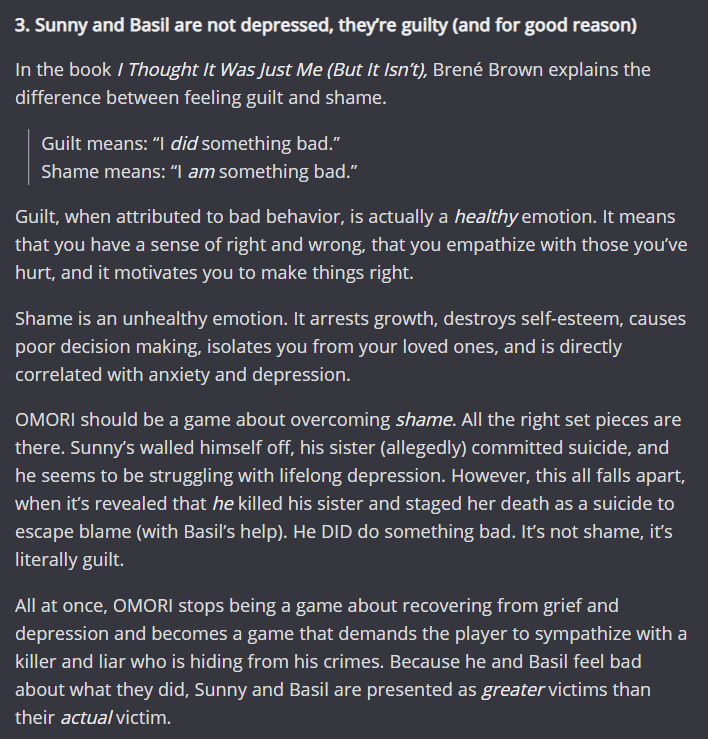

Omori – Aubrey: “What you’re dreamin’ about, Sunny? “

“… God I hate this girl.”

“… God I hate this girl.”

” … ”

” … ”

“So, first of all I respect your opinion but…”

“So, first of all I respect your opinion but…”

“But to me you remain a disacculturated bitch and know-it-all because you have not understood the beauty of this character because she is an absolute snack”, I would like to interrupt you and predict what you will tell me! ”

“But to me you remain a disacculturated bitch and know-it-all because you have not understood the beauty of this character because she is an absolute snack”, I would like to interrupt you and predict what you will tell me! ”

“Ele…”

“Ele…”

“‘Kay, that was too much. An” analysis “on Aubrey, however, would have distracted us from the conversation, come on!”

“‘Kay, that was too much. An” analysis “on Aubrey, however, would have distracted us from the conversation, come on!”

So, except for this small incident with the community, which has been celebrating this game for a few months …

Aubrey. I confess that she is the character that made me roll my eyes multiple times in Omori, as she is simply a more serious case of a problem that all the characters in the game have: the accumulation of stereotypes on stereotypes.

But most of all, the way she was treated lowered the quality of the game even more.

I see that you are already preparing the pitchforks or a nice little speech for me, which would go from saying how profound Omori really is, up to my total lack of manners… For some reason …

But let’s introduce her for a moment, this “Aubrey” with an unknown surname.

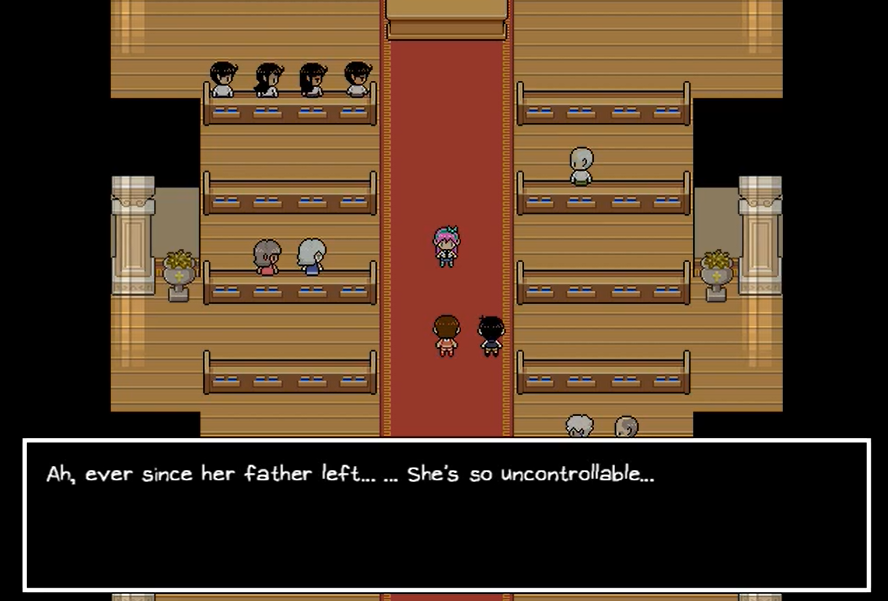

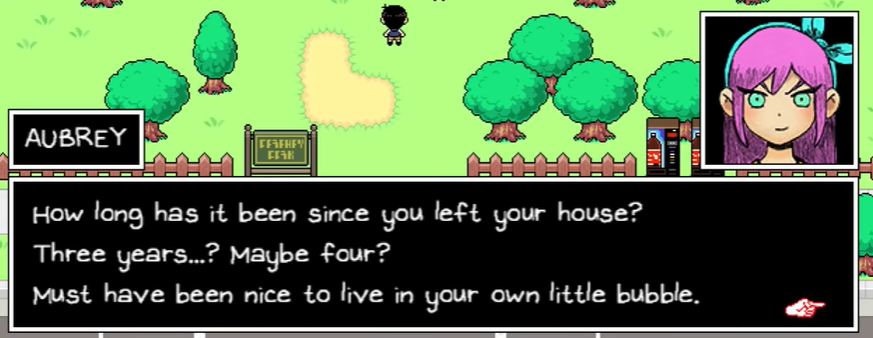

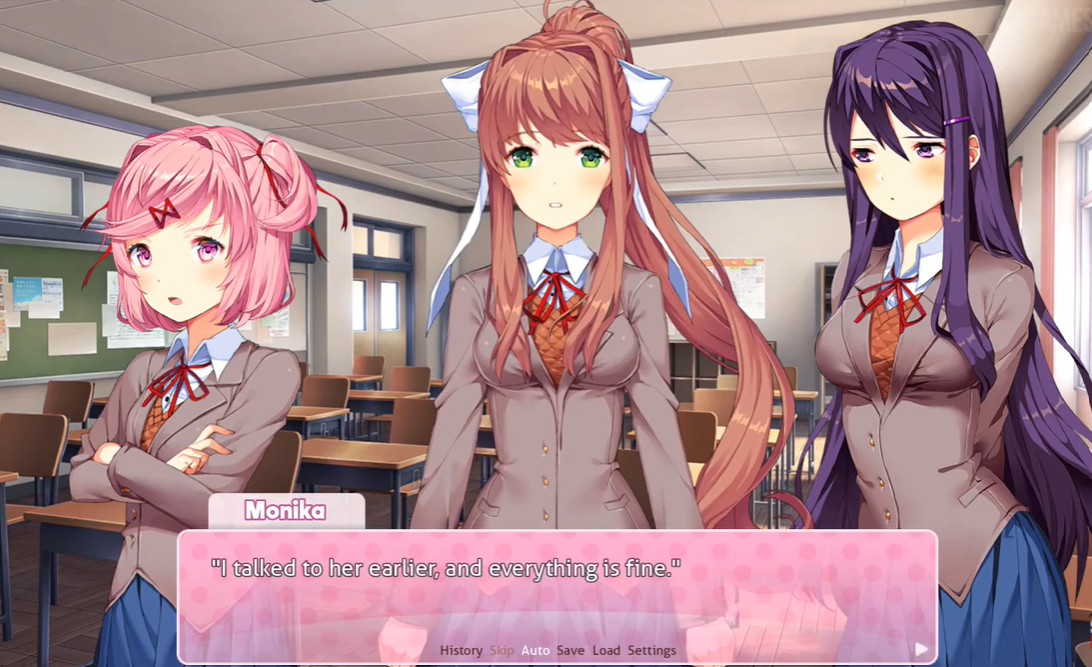

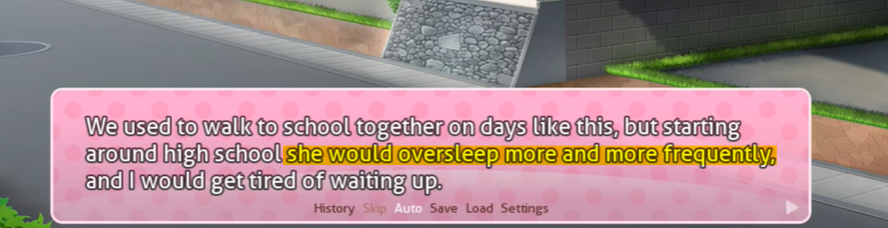

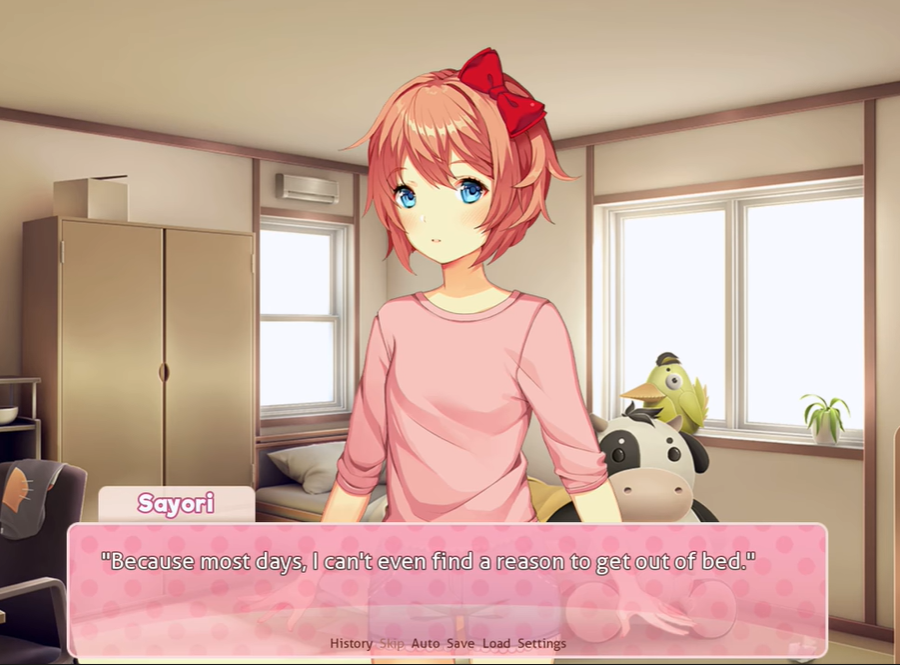

Aubrey, in the real world presented by the game; because Omori is divided into the world of dreams, where they are all children, and the real world, where the protagonists have all grown up, having been a 4-year timeskip, is an active bully who gets commands a gang (what a gang, they use bicycles to bully. Are they put down like petty thugs, and not even a bit of vandalism? Or something like that!) who beats up a poor guy for something that happened 4 years earlier than what we see through the eyes of the protagonist Sunny …

” Ah, come on! She’s doing it because she feels bad that Mari is dead, just like her father died, can’t you see? ”

” Ah, come on! She’s doing it because she feels bad that Mari is dead, just like her father died, can’t you see? ”

“Sure. And the water is definitely wet …”

“Sure. And the water is definitely wet …”

Let’s go in there with an in-depth look at her behavior for five minutes.

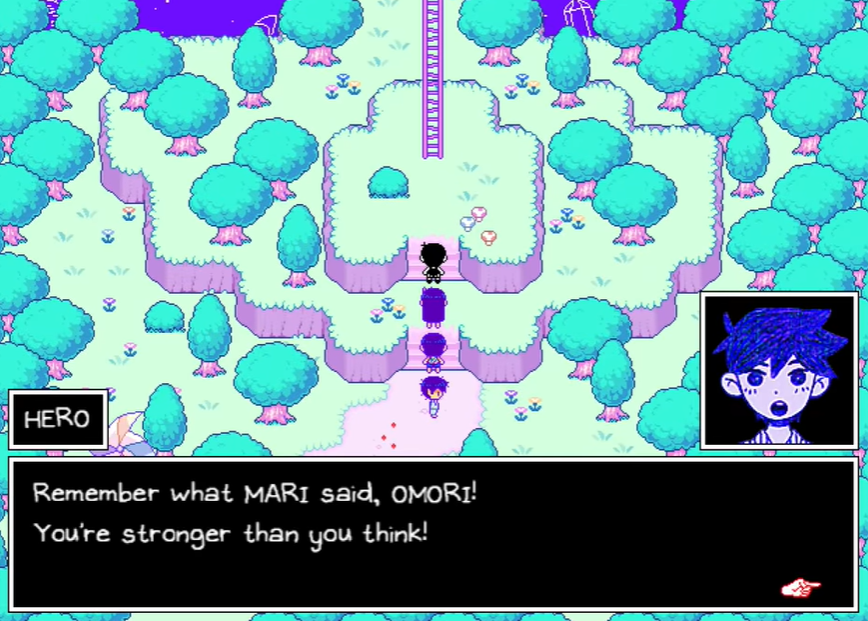

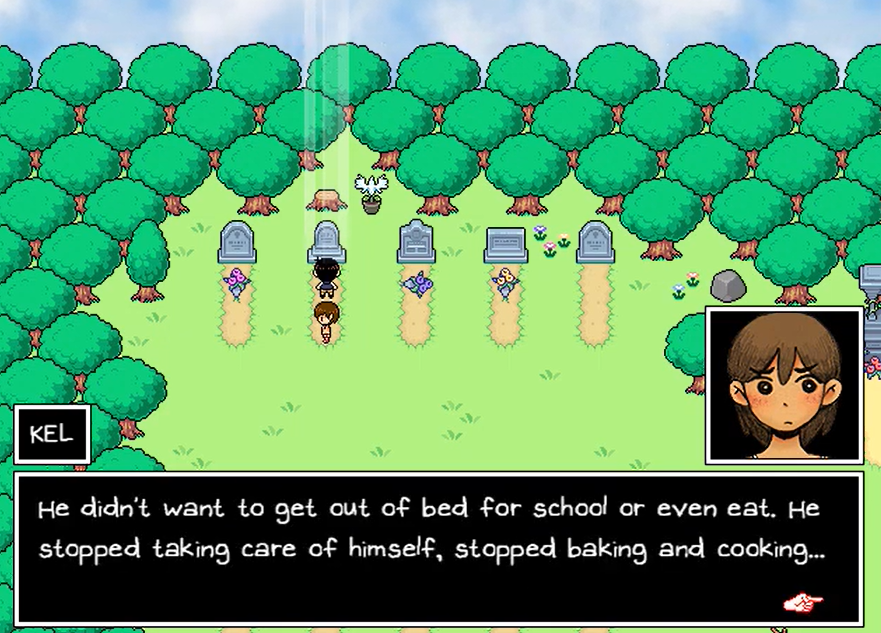

Aubrey has never and I say NEVER overcame her mourning for Mari , their friend, for 4 years (because there is a 4-year timeskip in the game), when Hero, another main character, despite being ( assumes) someone as close to her like her boyfriend went to college and passed it, in that time frame.

… And Aubrey above all still takes it out on her old friends. We can see such a nice display of maturity . She didn’t move on in her life after, let’s say it again, four years after mourning Mari-

“Hey, her father died too …”

“Hey, her father died too …”

“Ok, when? Did the two griefs happen in a short span of time, so that the despair was stronger?”

“Ok, when? Did the two griefs happen in a short span of time, so that the despair was stronger?”

“Well, I don’t know, I guess …”

“Well, I don’t know, I guess …”

“Yeah right, continue to suppose. Games look better to you if you assume everything.”

“Yeah right, continue to suppose. Games look better to you if you assume everything.”

“Oh. I liked this one.”

“Oh. I liked this one.”

…In any case.

Four years since mourning for Mari, we said. And, later, she will blame her old friends for not being there for her.

Another great demonstration of maturity, because it is said in the game that everyone was grieving for their dead friend, and that they all had their problems! And after four years, where she has already found other people (“superficial friendship” or not, as perhaps she wants to be treated) she has grown up even if in a negative way?

Another thing to do, without having to get to monkey-like violence, or acting like a capricious child , would have been simply not seeing them again, not considering them, without being a drama queen in church!

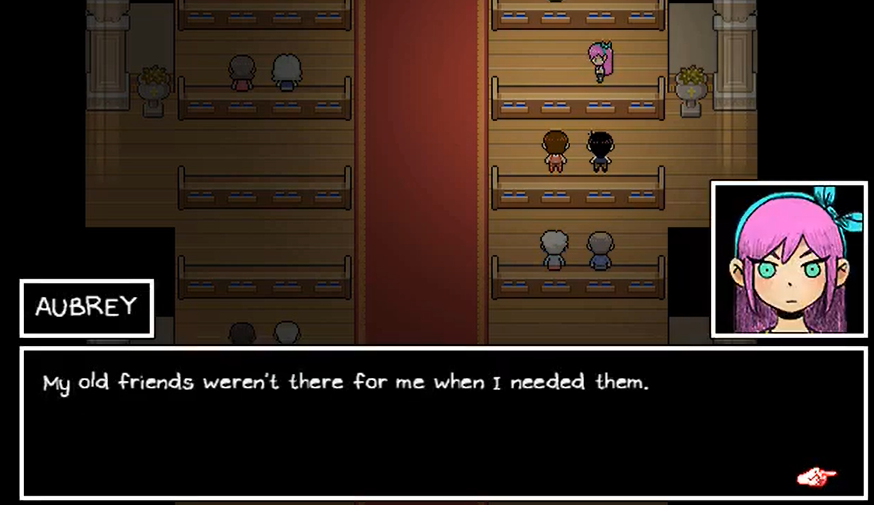

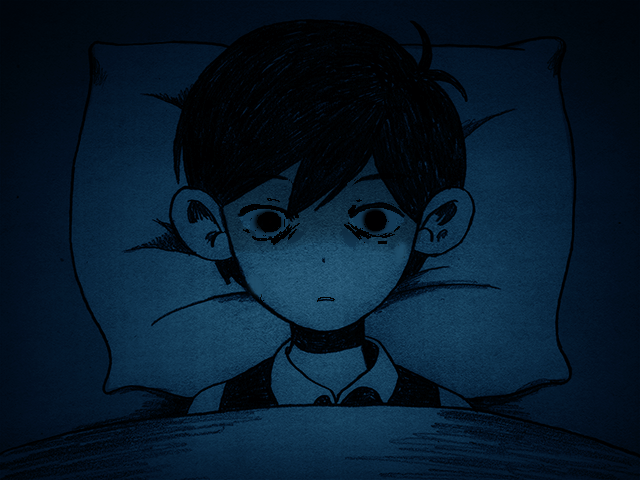

Here, now that I’ve complained very well about Aubrey …

You know what’s funny?

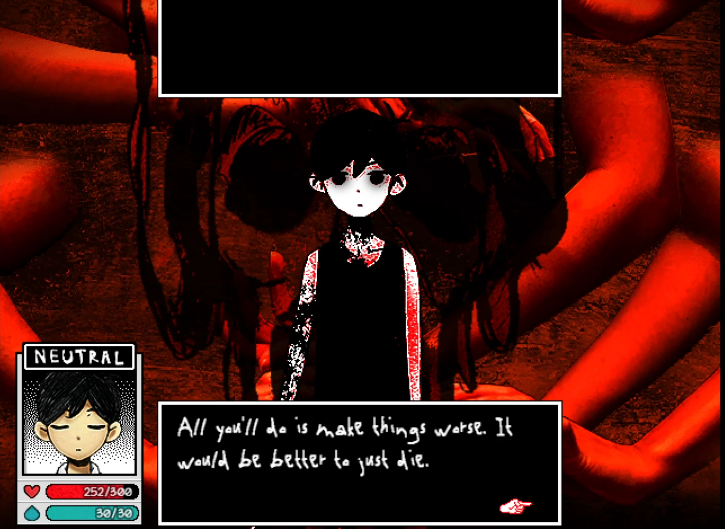

From her childhood Aubrey never grows up during the game. We want to see how the game treats her?

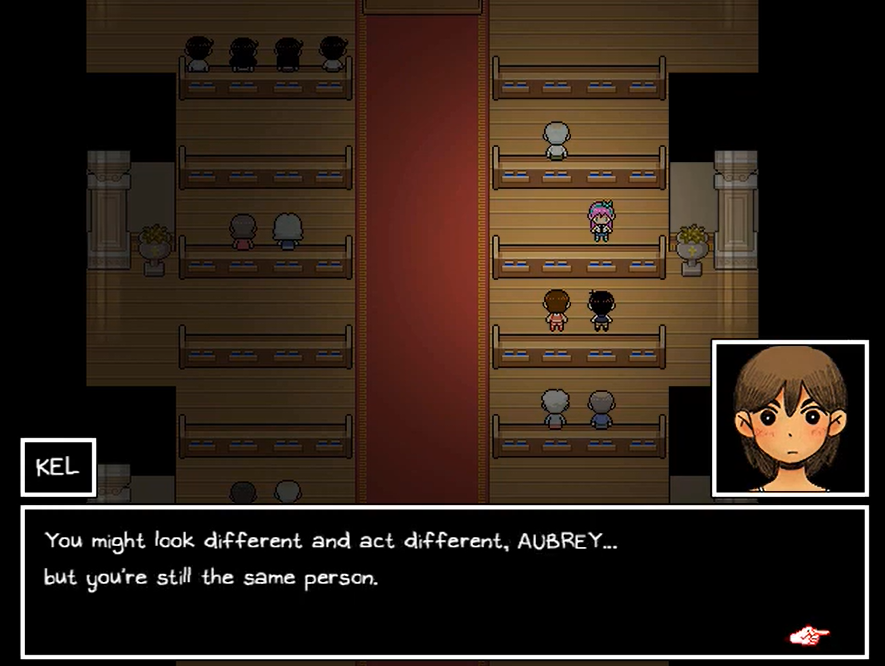

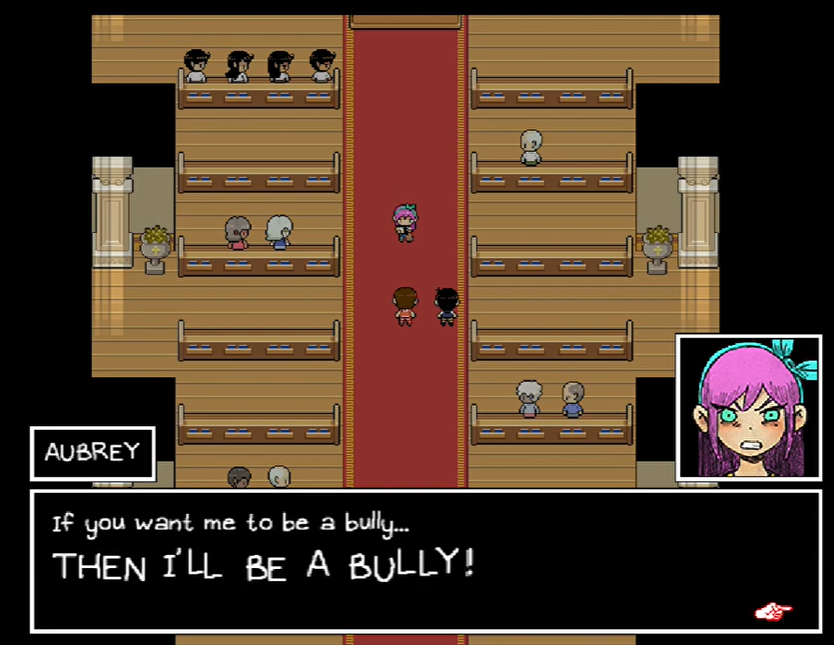

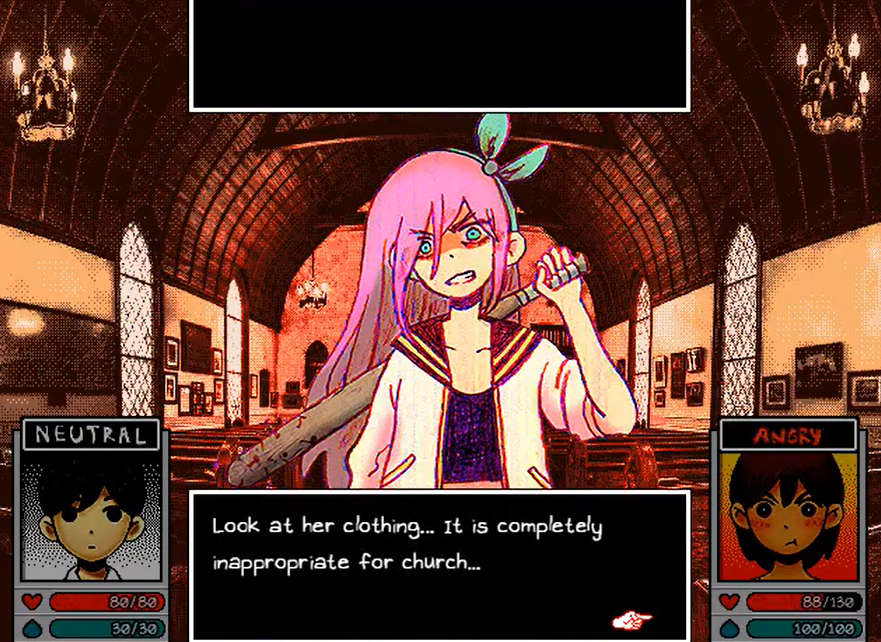

Let’s take a look at Aubrey’s character in detail through the scene in which she is directly protagonist, the scene of the church.

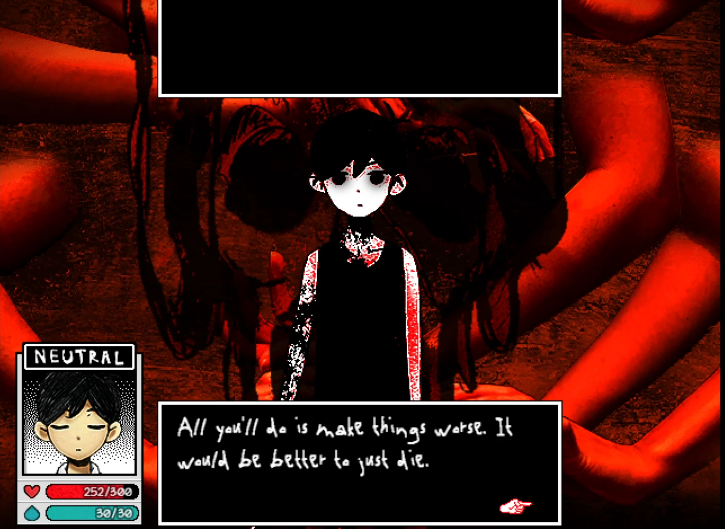

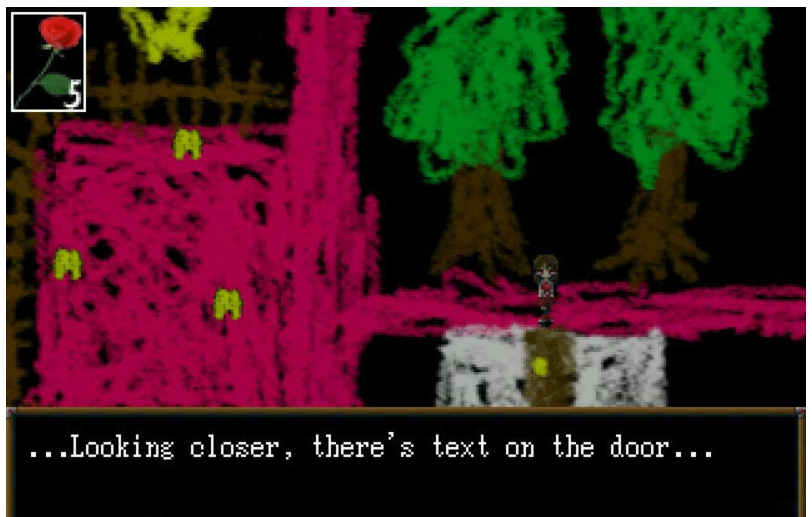

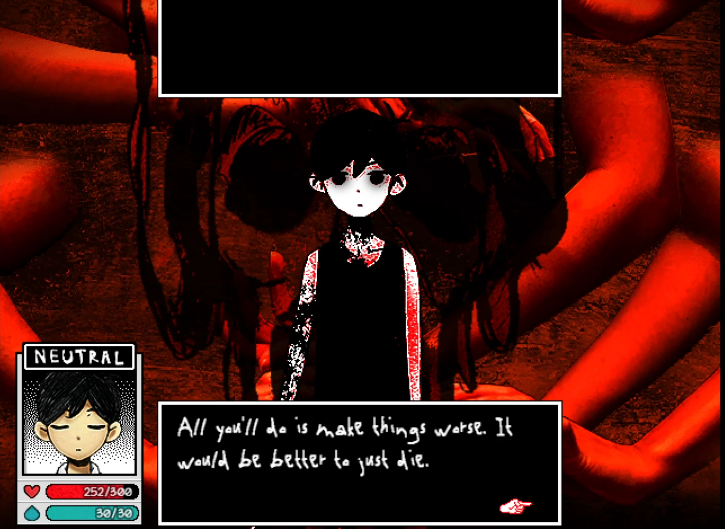

The scene where, honestly, a feeling of absurd cringe assaulted me , due to various factors of unrealism, including people who were neither going to divide them, nor to do anything for kids who beat each other, not even the priest did nothing… And above all, the random comments of people: “Look how she is dressed …” and shit like that. Of those classic things just to say “we live in a society …” , but which actually have no context (because first of all, such phrases in that situation they are really ridiculous … And then because society, after this scene, is always and in any case quiet and happy, so it is not a theme that is dealt with in the work itself – and for the record: Earthbound had a supernatural plot that distorted the balances of the “cute little village” , so everything was functional to the conflict that would develop -) and serve only to see Aubrey as a victim, when in reality she is the one with a NAILED BAT willing to beat us in a church.

Back to Aubrey …

Let’s skip all the useless dialogues about “We WERE friends, now not anymore because now I’m depressed”… Let’s go straight to the lines before the fight.

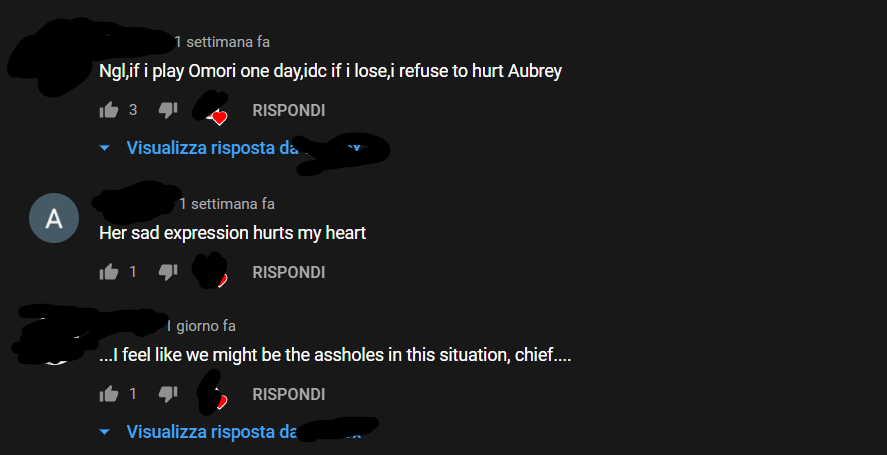

Let’s start with this sentence from Kel. It’s very generic , seriously, but from here we can start the phenomenon where a character becomes “the author’s pet”, “the fanbase’s pet” or … In general, is justified for everything because “underneath there is a heart of gold!”.

Guys. Let’s stop.

The ending of the game, according to which Aubrey finally makes peace with everyone she is a simple sop for those who love this character.

“To behave differently, but still be a good person, actually with a heart of gold, who has people he loves, and cares about them, even if he’s a little aggressive”, talking about characters who are potentially criminal, violent, or even just bad people …

I tell you something bad, but in my opinion it is very true.

Do you know where this unrealistic concept tends to apply?

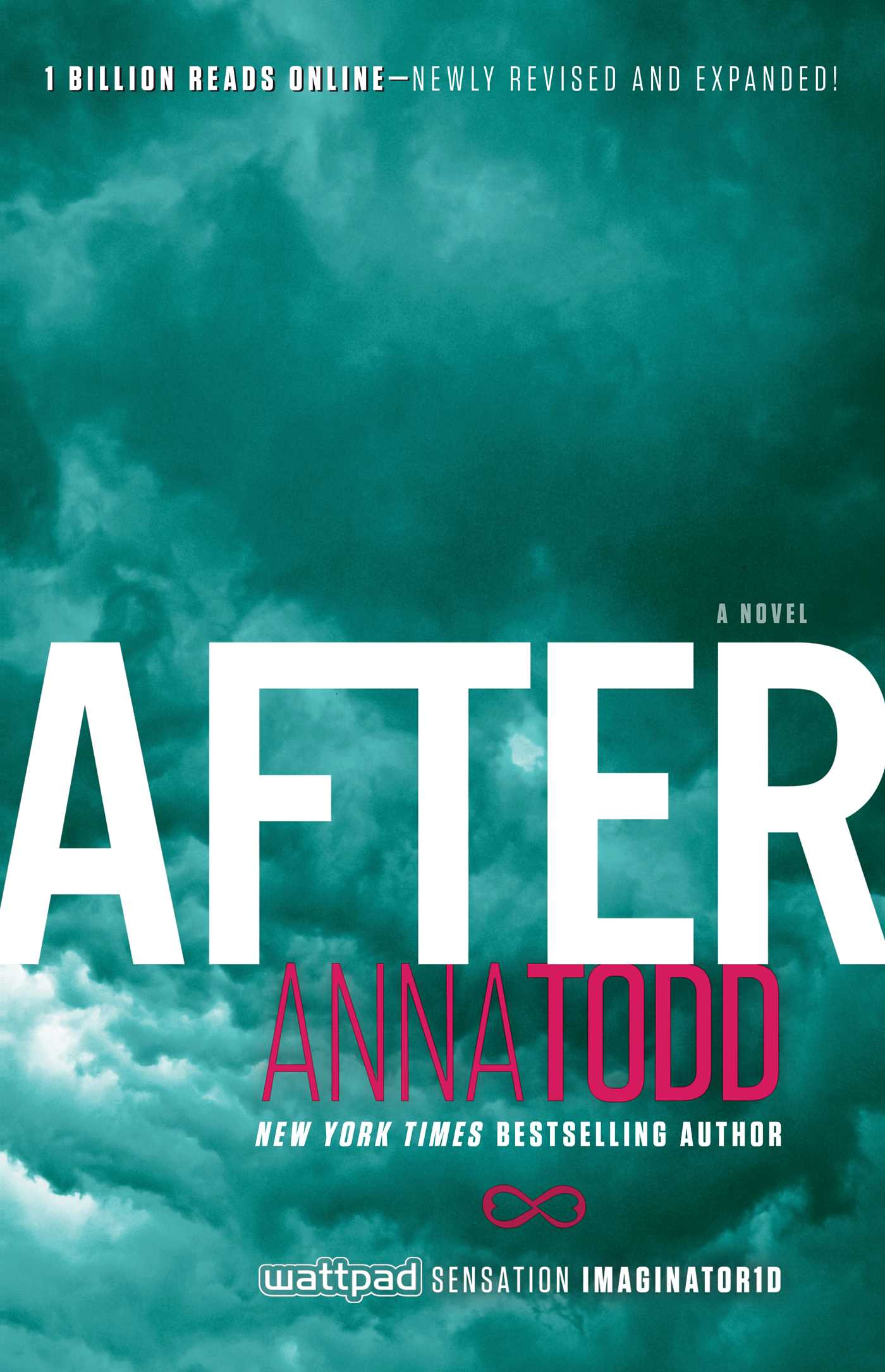

In young adult romance books. Trashy ones.

“After ?! SERIOUSLY ?!”

“After ?! SERIOUSLY ?!”

…

“… And one is gone. Okay, maybe I’ll be in real trouble if she starts telling herfriends“ I went to a convention of someone who compared Omori to After !! ”. Novella, if someone knocks do not open! ”

“… And one is gone. Okay, maybe I’ll be in real trouble if she starts telling herfriends“ I went to a convention of someone who compared Omori to After !! ”. Novella, if someone knocks do not open! ”

… Ele, I’m honestly worried about your actions.

… Ele, I’m honestly worried about your actions.

You know this book? Hated by many booktubers, a representation of a toxic relationship, because Hardin is generally a boy with multiple mental problems, never taken as such.

… And in general, on the part of the saga (the first two books that are the basis on which the others rest, practically) he is almost never condemned or no one has the correct reactions to his attitudes, due to the fact that it is love interest of the protagonist and love interest cannot be represented for what it is, for a sick person or at least not suitable to attend.

We should root for Hardin every time, even though thinking logically for some situations in the book would be right for other characters as well. No, Hardin will always have the best because he has to have the best in life.

Because the author likes him, because the readers like him. In theory, such a person shouldn’t even interest Tessa, if the always unrealistic trope of “good girl-bad boy” didn’t exist and vice versa.

A depiction of the bad boy as given by Hardin convinces readers that even a dangerous man, such as Hardin can, with the right person change, can be “fixed”, because he has a heart under the stone.

Ah, the more pretentious call this “character development” of these types of characters.

Because these thoughts “comfort” the readers, when the reality is very different.

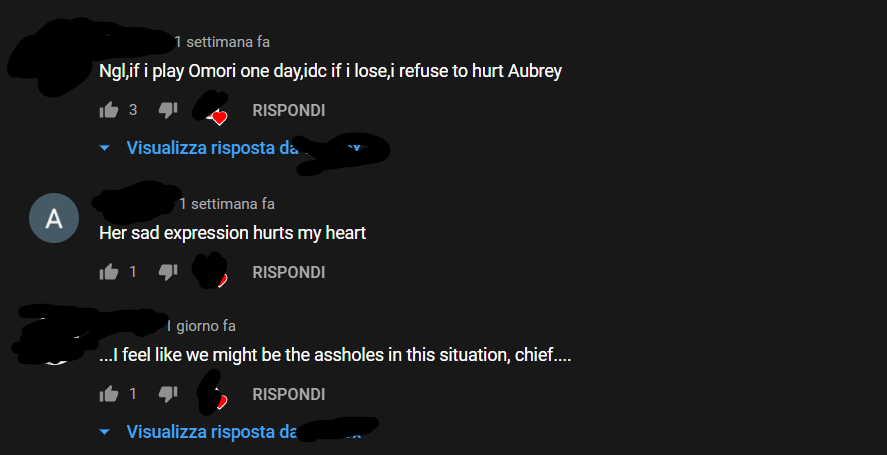

Don’t look at me like that! You know it’s true, you know you have the same dynamics as romance book readers! I can summarize you your character evaluation path with a very simple list!

-

Wow, what a cool person.

-

Damn they’re tough, they beat people up. Oh, it’s not morally correct, but they remain cool… Although I don’t know, is their beating *** …?

(Sorry, I couldn’t find a better frame for the scene where he hits a guy at a party. In the first film he hits a lot less than in the book and for the second film there is no convenient compilation of ” Hardin Scott Scenes ”and I don’t really have the heart to see the second film in full)

-

Aw, it happened ( insert trauma, death of parent, or … Anything bad at this point, is good) then. Ahh I get it, they try to defend themselves from what they felt. How sad, I understand why they’re doing this…

(This scene shows Hardin’s backstory, where his mother was raped and he had to see it all)

-

Actually in this round we are the bad guys who are limiting *** to express themselves. Please defend this person!

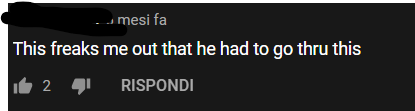

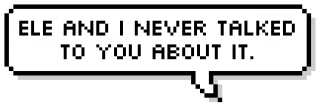

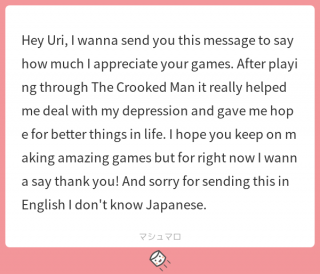

(The ones above are comments below a gameplay where the church scene in Omori is seen)

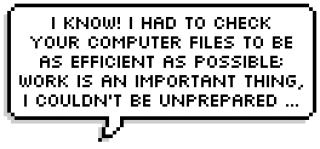

(These last 3 are comments under a nightmare scene in the second movie on After, where Hardin’s backstory is known)

Just like Tessa, also in our case for certain types of characters it is not the reason that speaks. It is the desire for a comfort character at all costs and our Red Cross syndrome to speak.

“Hey! Red Cross Syndrome is different from simple empathy!”

“Hey! Red Cross Syndrome is different from simple empathy!”

“If for Aubrey no one had used the same reasoning as” we can fix her! ” used with Hardin, Sunny and Kel would have helped Basil and left Aubrey to herself, because she is a girl who, at least in the way she wants to pass, is dangerous. ”

“If for Aubrey no one had used the same reasoning as” we can fix her! ” used with Hardin, Sunny and Kel would have helped Basil and left Aubrey to herself, because she is a girl who, at least in the way she wants to pass, is dangerous. ”

I basically have a comment on Hardin that speaks for me.

Do not take into account the lack of the double. I also ask you this question.

If, for example, Aubrey was actually aggressive towards Basil only as a typical bully: because she is having fun (or for real discrimination, then we can address this later) …

We would like her as a person?

Or, given that we really like the concept of “characters as people”: if we didn’t have the game that clearly tells us that Aubrey is a person to help … Would we like her? Would we think of her actions as “immoral, but done for GOOD reasons”?

I don’t want answers here from the public. I leave this question open.

Also because I want to move on to another case, in which the work grimly justifies not whims such as words, or even physical violence given by immaturity, which is not given its own condemnation in favor of a real character development …

In the next and last case, the one for which Victor Frankenstein was badly punished in Mary Shelley’s novel is justified.

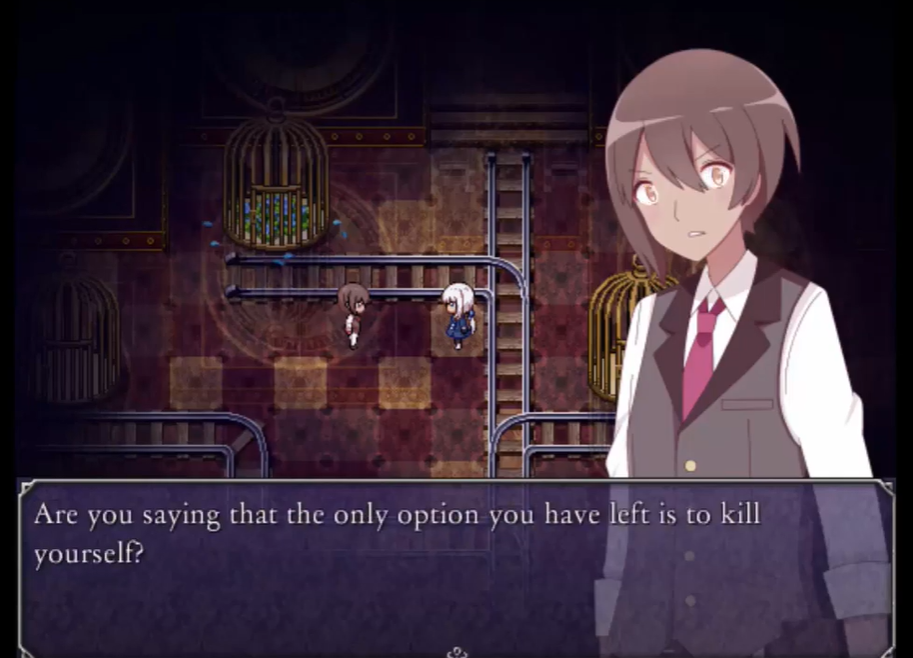

Aria’s Story – “Clyde’s Story”, or The Modern Prometheus

“Aria’s Story! Nice, it’s the game that got me close to Horror RPGs! ”

“Aria’s Story! Nice, it’s the game that got me close to Horror RPGs! ”

“…”

“…”

“But why do you compare those cute people, like Clyde, to a boring classic from the 18th century?”

“But why do you compare those cute people, like Clyde, to a boring classic from the 18th century?”

Because that’s exactly what we justify for all of Aria’s Story, especially the dialogue added in later versions of the game.

The case of Clyde is almost funny, as surreal as it is.

And above all it makes me laugh, so as not to cry, how the basic direction of two / three tear-jerking scenes managed to obscure this truly disturbing aspect of the game, on which, however, in the end nothing was ever deepened, nor even thought about it as a real problem, or a moral doubt.

I can’t even write any catchphrases … Because the problem lies in the whole plot!

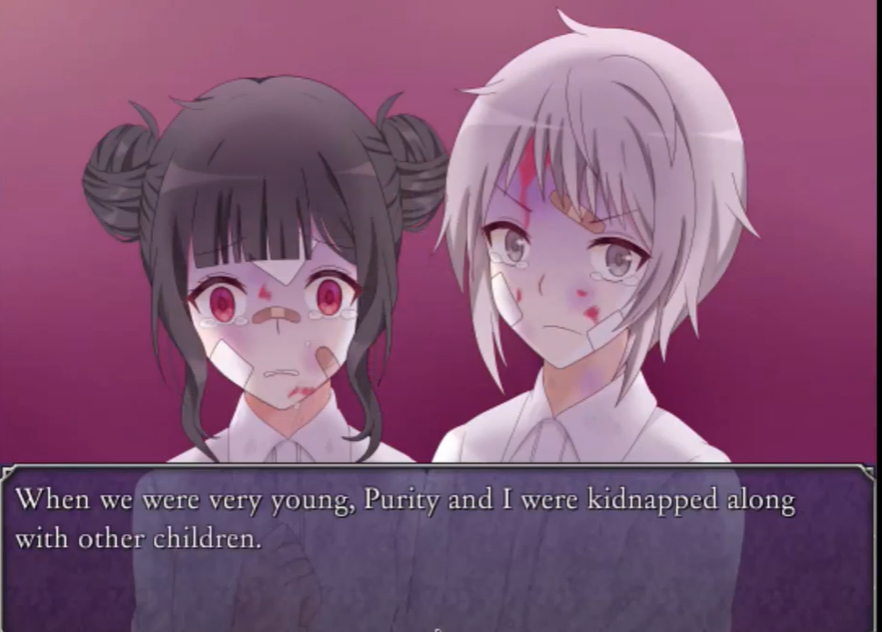

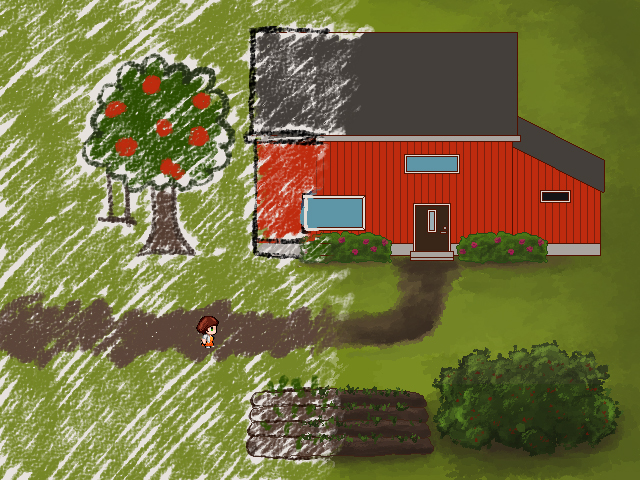

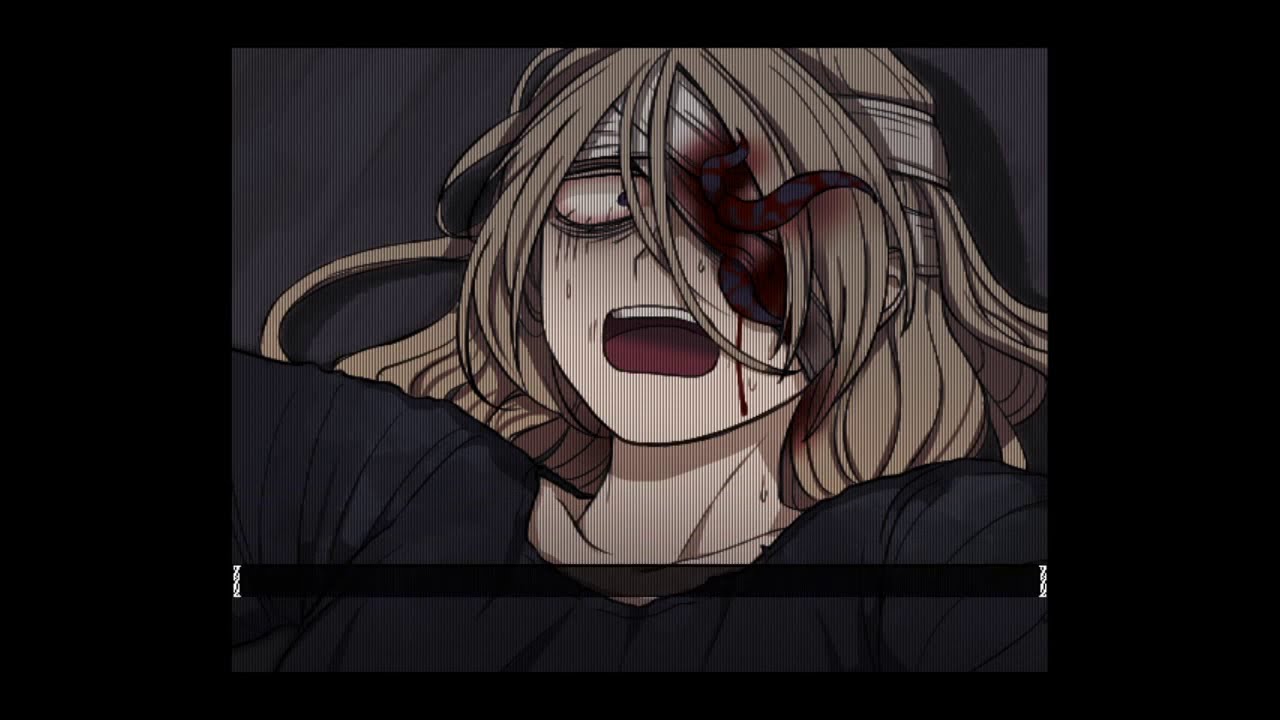

For those unfamiliar with Aria’s Story, here is the plot in brief. I just want to inform that it is all put into the final few cutscenes, while for the whole game we have only a foreshadowing put there and in general the cosmic nothing.

Juust some small inspiration from Pocket Mirror, huh?

“Pocket Mirror? But Aria’s Story-”

“Pocket Mirror? But Aria’s Story-”

“Shh… You may complain later.”

“Shh… You may complain later.”

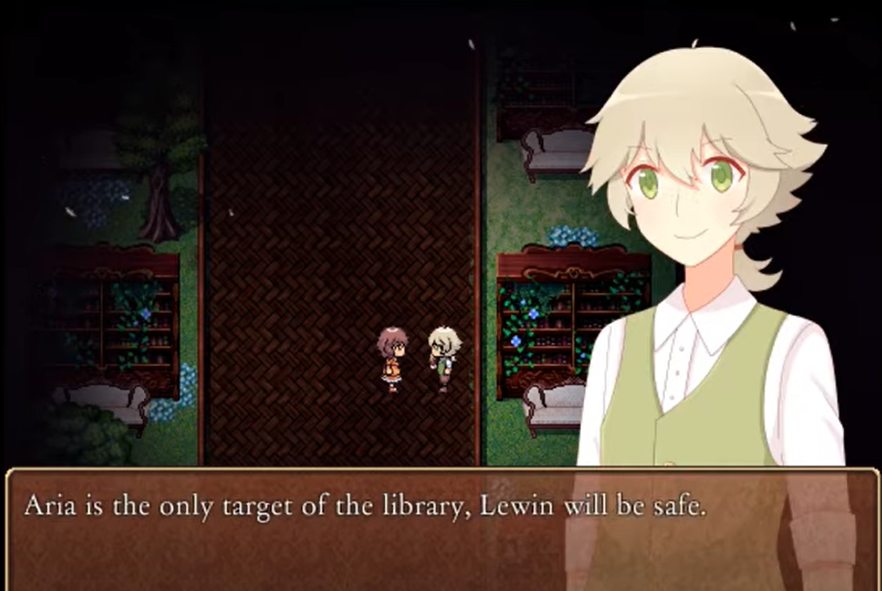

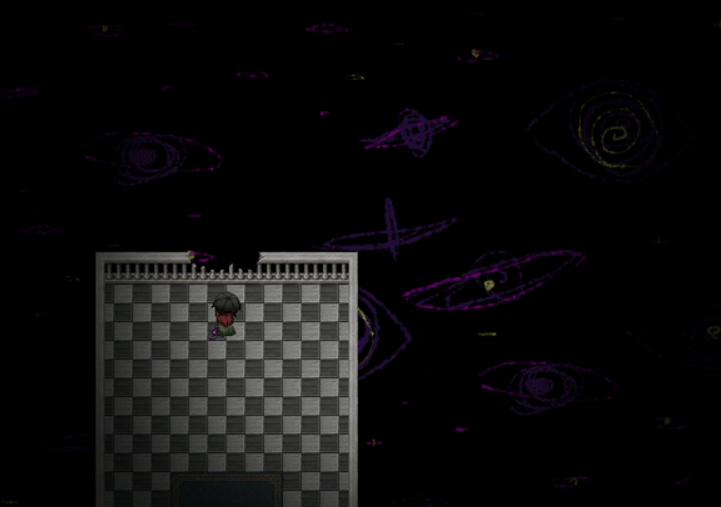

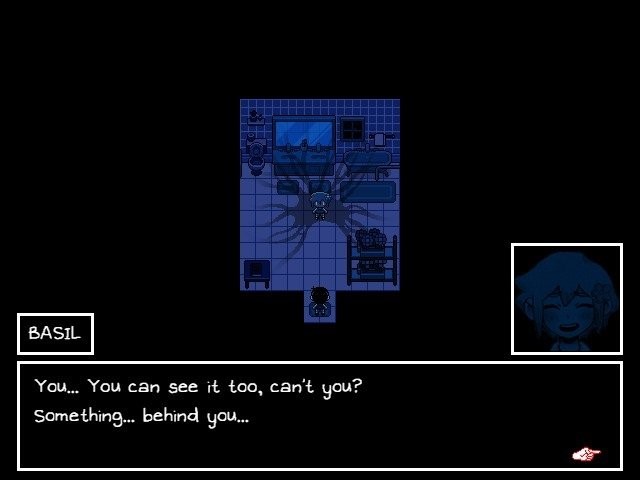

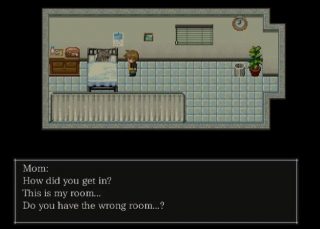

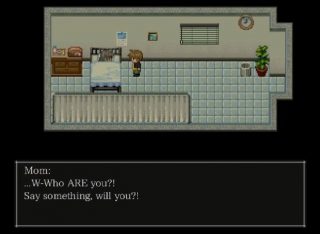

The general plot-twist of the game is that the protagonist we have been in charge of all the time, Aria, is actually a copy of a dead girl, friend of the supporting characters we will meet during the game. Clyde, the creator of it all, with a magic pen (??) desperately wanted to bring back the real Aria. The “False Aria” was created with the magic pen, as well as a fantasy world based on the book of Lewin, part of the group of friends that Aria was part of (which includes all the characters).

Clyde wanted to test if the fake Aria was as good as the real one , so he trapped her in the world of books and brainwashed Dahlia (their other friend … Same role as Aubrey: bringing drama) and Lewin so they could guide Aria through her journey.

I’ll build on what the game actually tells us via seemingly useless dialogue between Clyde and Dahlia, and True Ending.

Since I’m going to talk about Clyde, I won’t be interested in the “Good Ending”, where the “false Aria” accepts that she is someone other than Aria. Mainly because it is … Simply a really embarrassing ending, put into a last minute-update.

“But how? That ending is essential! You called the paragraph” the Modern Prometheus “, and you don’t talk about how Wendy managed to recognize herself as a single person and not as a copy of Aria?”

“But how? That ending is essential! You called the paragraph” the Modern Prometheus “, and you don’t talk about how Wendy managed to recognize herself as a single person and not as a copy of Aria?”

“… You know we’re going to talk about Clyde, right?”

“… You know we’re going to talk about Clyde, right?”

Guys, the problem is not Aria’s reaction in alternative endings like Bad End 2 where she kills him so randomly or Good Ending where in five minutes she has an existential realization and above all how this ending creates some huge holes with what we have always seen in the game until the end …

For example, throughout the game we do not see a girl other than Aria, on the contrary we see a perfect copy of her also from the point of view of her personality. Besides, this magic pen is defective for example having created a totally different person! Clyde had to create a perfect Aria! It is a magical medium above nature not, in fact, a scientific experiment with unexpected events or bad brains, like Frankenstein Junior!

It’s the really troubling and disturbing plot premise, which makes that guy compare to Victor Frankenstein!

So, starting this damn analysis on Clyde …

I wanted to separate one piece of plot from all the others.

“Clyde wanted to test if the fake Aria was as good as the real one.”

If “Aria” didn’t prove to be an obedient creature, what do you do then, Clyde?

Meanwhile, the Aria just denied by its creator, which has met with who knows what fate:

… You have the possibility to create life from nothing . You can create human beings as you please, fully thinking beings, with their own intelligence, questions, hopes, ambitions! Not robots!

And the life you create, you treat it like this. “If he dies in this world, I create a third, fourth, tenth Air …”.

So, automatically, “If it doesn’t satisfy us, we can kill and make another one that can satisfy our desires”.

Do you realize? With Clyde’s mentality, “Good Ending” could not even be contemplated , because an Aria that did not respect Clyde’s canons would be killed. The fact that the various “copies of Aria” had to even be “tested” says it … It wasn’t enough to see if Aria talked, walked or managed to articulate thoughts. No, we needed the Aria that Clyde wanted .

The slightly more realistic ending (although I always sin of any kind of depth), therefore, is actually the second Bad End where, as in Frankenstein, the Creature kills her master! Victor is punished because he has broken the laws of nature and repudiated what he himself created!

I … I don’t know what to say, even though I know I have to talk because if no one has noticed this very disturbing detail, I have to tell the details!

Speaking precisely of Frankenstein, to go directly to the point, or how this horrible attitude towards a new life is treated … Victor is questioned and eventually even killed, precisely because of the concept that Clyde says!

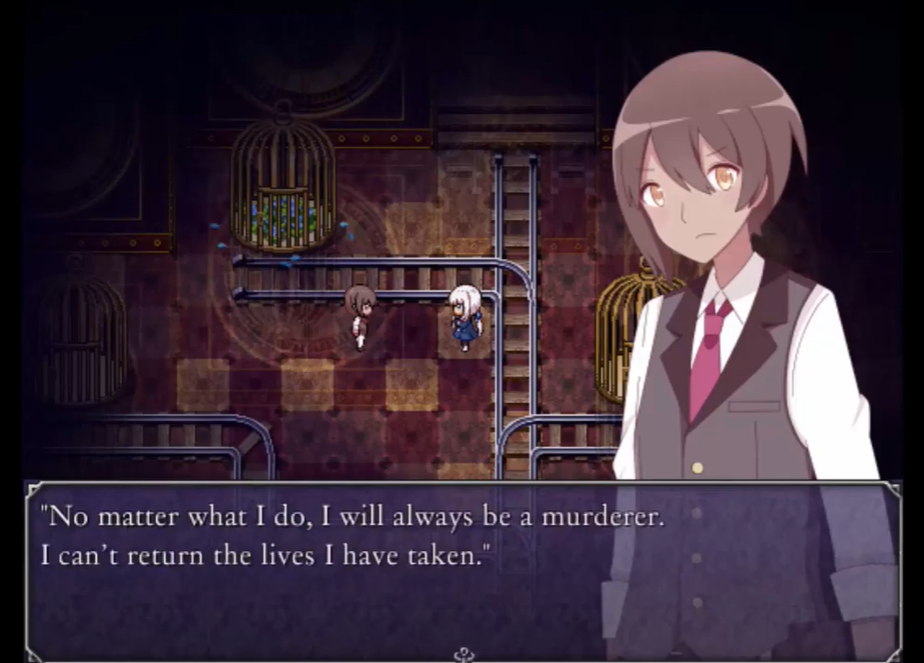

This sentence says it all!

“And you, with a satisfied conscience, would destroy your own creature!”

(And, in the final …)

Ah, I forgot.

Thinking about it, even the element for which he DELETED MEMORIES – Once again I wonder what other incredible feats this damn magic pen has – to Dahlia and Lewin makes me think that Clyde did not want anyone to counter him under any circumstances. This adds further concerns to-

“That’s not true! He did it to protect them, and then in the end he was thwarted anyway, can’t you see ?!” that’s a bad idea! ” Lewin said it! ”

“That’s not true! He did it to protect them, and then in the end he was thwarted anyway, can’t you see ?!” that’s a bad idea! ” Lewin said it! ”

“… I was just talking about it, flower girl.”

“… I was just talking about it, flower girl.”

So, even if against this ideal there is also a tiny clash with Lewin along with a tiny afterthought …

After two dialogs, everything Clyde did and thought about doing is quickly forgotten because “now we cry”! An apology with crocodile tears and a “Clyde …” are not enough to say that this problem has been solved. Possibly, the whole game could have been based on this thing! This theme, that of the low value for life that Clyde has, is sinfully put aside and we will see why later.

So, summing up everything Clyde did, just to see what kind of person is justified … And just because I want to have fun, if possible I’ll compare his acts with phrases from any adaptation of Frankenstein, or the original book:

-he brainwashed friends who must have been involved in the madness he was doing.

(From “Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein” by Kenneth Branagh. I can’t digest it, but it’s still an adaptation of Shelley’s myth)

-He brought a dead girl back to life, not respecting the circle of life, and violating the laws of nature

(“It’s alive! It’s alive!” – Colin Clive, “Frankenstein”, 1931. Victor never says “he’s alive!” in the book. The famous phrase comes from this movie.)

-He expected his creature to look exactly like the one who was a dead girl, and if it didn’t pass a so-called “test”, if Clyde’s creation didn’t prove what it wanted … It deserved death, since has set deadly traps.

– Depends on how many times you die in the game, but he literally created multiple copies of Aria, with no conscience on the ones slaughtered by countless traps of her goddamn world.

And therefore, even if I have already mentioned it in many parts of this paragraph … It is all justified , and this is the truly incredible thing and … Yes, of the same level of restlessness as Clyde’s actions!

But why, you ask?

But for us, of course.

To give us a cute and conforting storyline of course-

“…”

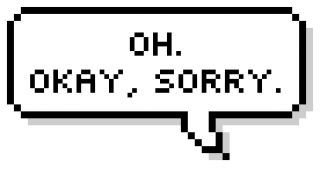

“…”

“Well, it was actually done because a creepy storyline with a half-sick character wouldn’t have been good for the game.”

“Well, it was actually done because a creepy storyline with a half-sick character wouldn’t have been good for the game.”

“Uh … Yeah … Aria’s Story wants to talk about something else … Clyde characterized in that way would have gone out of style …”

“Uh … Yeah … Aria’s Story wants to talk about something else … Clyde characterized in that way would have gone out of style …”

Oh yeah?

I tell you, would have actually made the “contrast between cute and disturbing “that the author of the game says so much in the bonus room at the end of Aria’s Story!

And then … In a horror game, would a character who made abominations go “out of style”? I am sorry to insult directly, but … Do you listen to each other again while you speak?

Finally: Aria’s Story, what are you talking about then, if a really defined and very strong theme (expressions used in a, I think quite appropriately, ironic way) permitted Clyde to behave like this?

“… It talks about friendship. Clyde did what he did for Lewin. He’s not as sick as you say.”

“… It talks about friendship. Clyde did what he did for Lewin. He’s not as sick as you say.”

“… Is it bad that I am anticipating all your answers to my questions?”

“… Is it bad that I am anticipating all your answers to my questions?”

… If he made all that mess for his friend of him …

Why did he feel compelled to do it all by himself? Why couldn’t they all agree?

Because it was madness , to bring a dead girl back to life. Lewin did not agree, Dahlia… We don’t know…? I have already said that: Clyde did not want anyone to oppose him, as he would have tried in a single dialogue window to do Lewin himself against him.

So, guys, I hope I have answered your questions … And that we can all conclude that Clyde is a totally unjustifiable person, now that we have all thought of it together (Again, irony reigns supreme) objectively .

But … We never thought about all this, seeing the final cutscenes of Aria’s Story. We’ve all been twisted.

Continuing my speech, we wanted to give a nice storyline of course, in a happy world where all friends are “one for all and all for one”, where people have their weaknesses and frailties, but that’s enough the comfort character on duty to let them pass them and make them become more perfect than they really are.

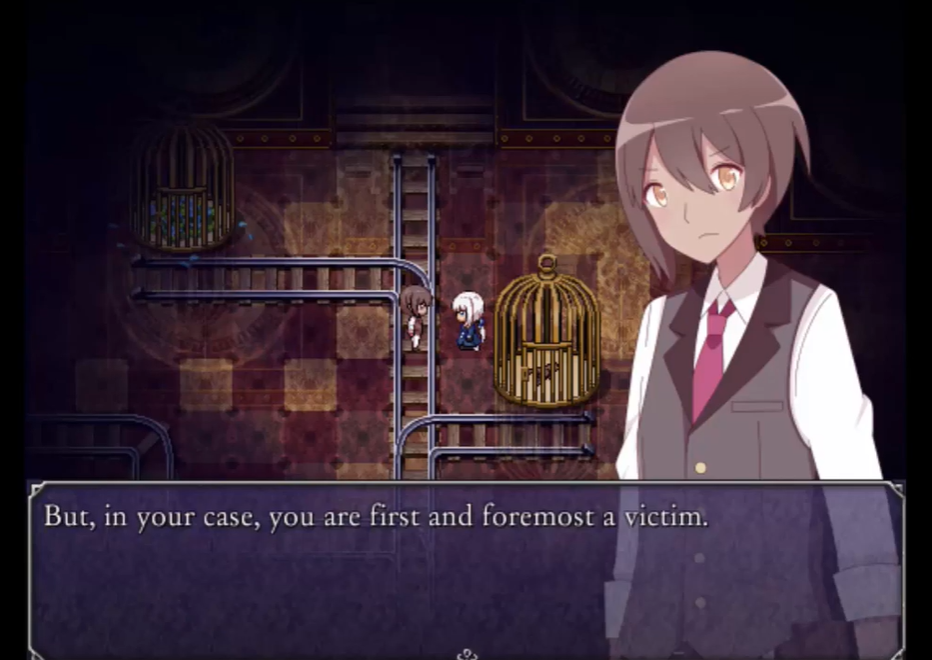

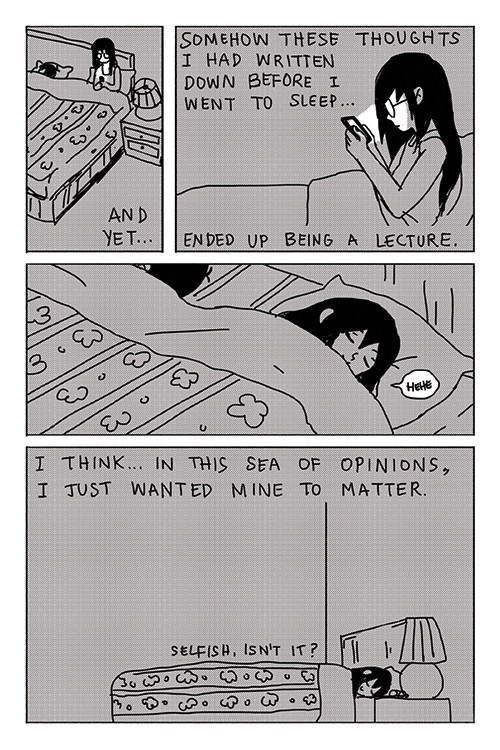

(This statement explains many things.)

Aria’s Story 2.0 – Bonus Room

“Wow that’s great! Really great!”

(Dialectal roman expression to indicate a catastrophic situation)

Here, precisely …

We like that world. That world comforts us, it makes us feel good to think “people have strengths and weaknesses, but we must always improve ourselves to become the best we can!”. A noble ideal, but one that we know very well that we do not know how to fully respect it. We know that we people are much more multifaceted, much more complicated than that.

However, since we really like that world a lot …

When cute little guys cry, we cry too . Even if all this has no context, it has no basis on which to stand, and it has so much rottenness underneath. We see beautiful faces crying in a crappy scene, and even if we had total nothing before, even if we didn’t have any path to get to that final climax … That scene moves us, so much that we cry.

It’s because we are the problem.

“…”

“…”

“…”

“…”

“… I wanted to talk about video games, not have a lecturer. Goodbye.”

“… I wanted to talk about video games, not have a lecturer. Goodbye.”

“…”

“…”

“She left in time … Now there should be …”

“She left in time … Now there should be …”

Part 2 – “I finally understand them!”

Therefore, we have now introduced a discourse that will be thoroughly investigated in this second part of the article on the “Selfish Confort Dilemma”.

Do you know why I dealt with these three cases of recent games (except for Cloé’s Requiem) in particular, to finally get to the heart of the whole discussion?

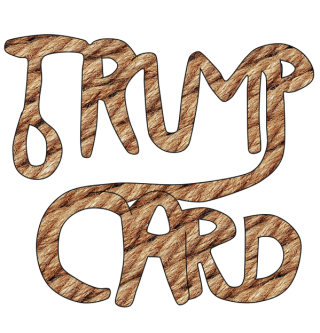

Because all three have one element in common: childish whims that are taken as real suffering or real reasons to act in extreme ways.

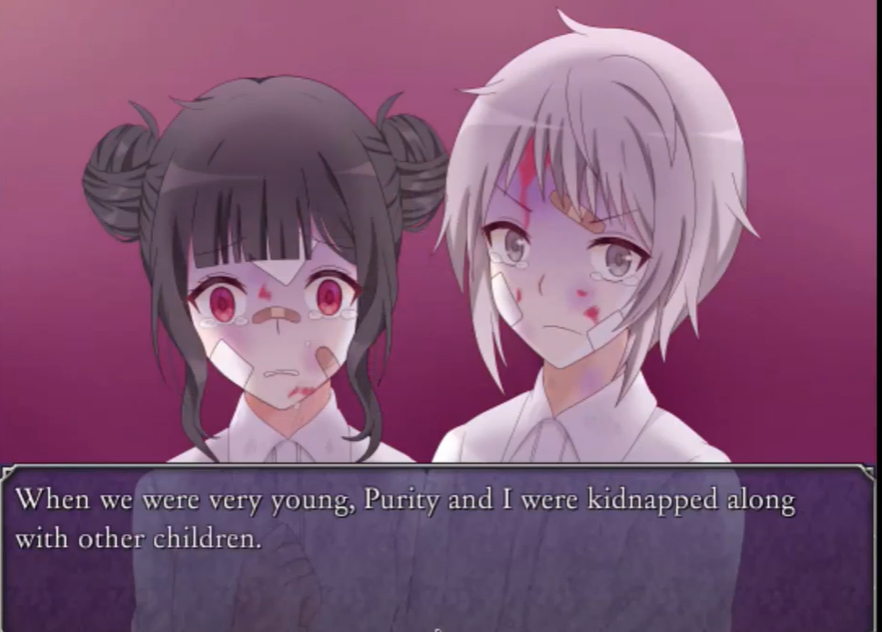

Pierre, out of his pent-up frustration, literally told his brother to kill himself.

Clyde, to bring back to life a girl who for Mother Nature had to end her existence, created or intended to create multiple creatures that he most likely could kill him without hesitation.

Aubrey, because of what a series of childish tantrums is in all respects, is considered dangerous and violent as well as being the reason why Basil suffers from bullying.

However, we have said it many times, these whims have always been justified by the works themselves . And do you know why?

Because the characters are put down as victims.

“You had an expression of pain.

The performance didn’t seem funny at all. “

Hmm … Honestly, I only have five words to describe these things.

However, returning serious for a minute, I can react as I want but surely to see those scenes you will recognize yourself in the series of comments that I put as the penultimate image.

You feel that you understand the reasons for these characters, who are more human to you … Because they are weak.

I tell you one thing. This is not understanding. This is victimizing and justifying, what I am condemning from this whole article.

I will explain better what it actually means to understand.

“Understanding” means understanding the reasons why a certain act has been done, but not necessarily saying that it is right, that the one in front of us is actually a good person, or even just someone who is “likeable”. A character we understand is a character that the public is not forced to redeem, but who remains from the complex and logical psychology in his actions.

What does this philosophy remind you of?

The antiheroes . Anti-Heores are nice, huh? We all like them.

The antihero, basically, is used in modern fiction as a “darker protagonist” . In the modern panorama, due to the bad interpretation of this role in a screenplay, these pseudo-antiheroes are also justified, but as a more precise definition we can see that …

“The Antihero is an individual who – from the very beginning of events – has no fear of showing the darker side of his personality. The salient traits of his personality can range in any direction, from selfishness to violence, from reach to shyness, from fanaticism to submission to reach and exasperate every other human characteristic. His vision of his world is often not very lucid and not at all inclined to the rules of good living. ”

(from the site Scrittissimo.com )

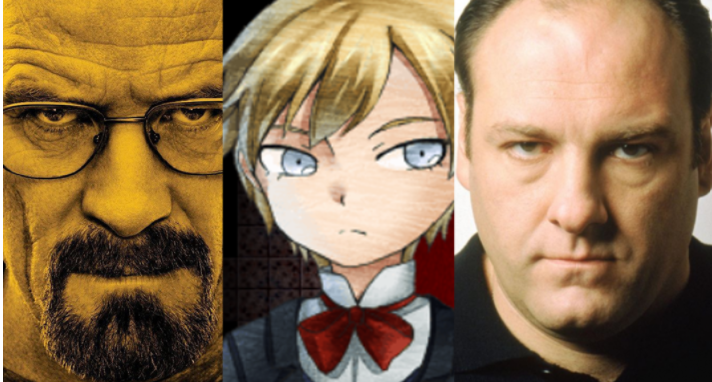

-Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, Cloé’s Requiem: moral conflict and the essence of the antihero-

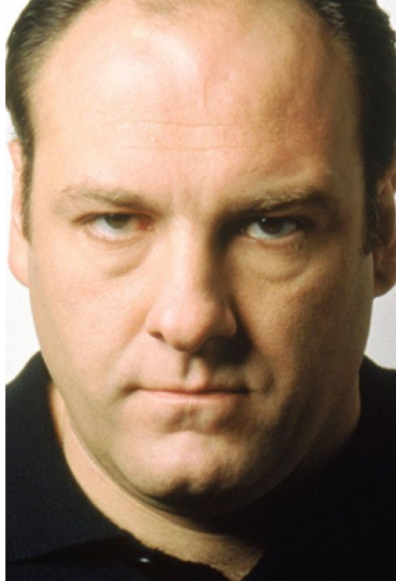

To better connect to what we are talking about, we go for three different cases : one is part of the type of video games we are talking about on this site, the other two are iconic characters of the series landscape – Walter White and Tony Soprano.

“Do you really want to compar a crappy game like Cloé’s Requiem to Breaking Bad or the Sopranos ?!”

“Do you really want to compar a crappy game like Cloé’s Requiem to Breaking Bad or the Sopranos ?!”

“Whoa calm down, we criticized Cloé’s Requiem as much as you want, if you hate it so much …”

“Whoa calm down, we criticized Cloé’s Requiem as much as you want, if you hate it so much …”

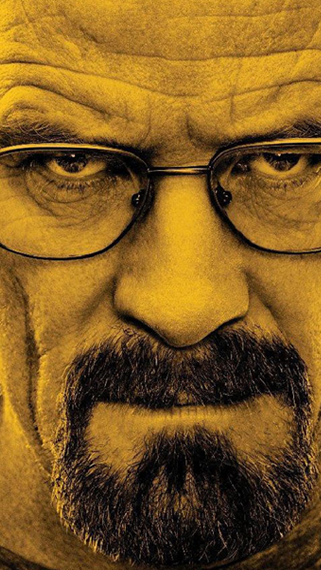

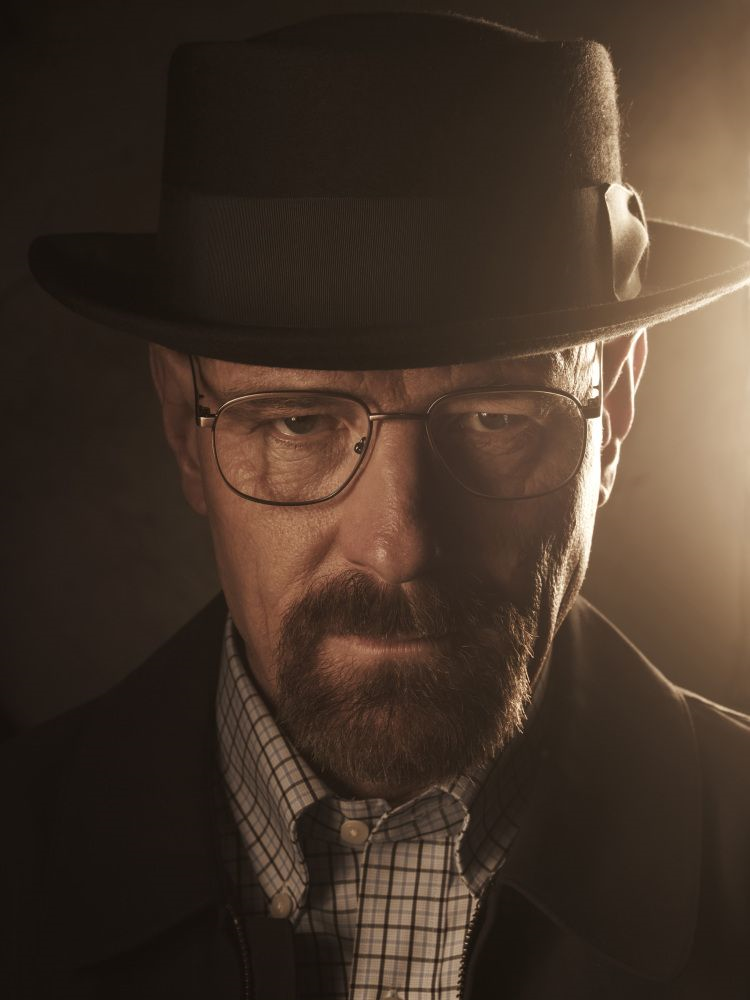

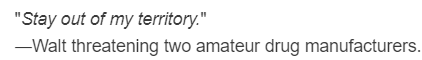

Walter White – The “OG”

Let’s start with one of the most praised and appreciated series of the last ten years , to get a general idea. I say “general” because Walter White’s psychology is far too complex to cover so briefly, as it constantly evolves throughout the series… And I honestly haven’t even seen Breaking Bad in full. Don’t point the pitchforks at me! I’ll get help from the wiki, which describes Walter White’s psychology very well, when we should mention it about episodes.

But in any case I believe that every nerd on the planet knows the origins of Walter White.

So, Walter White is a chemistry professor, not paid enough from his teaching job, nor from a second job in a car wash.

Walter, after this presentation of his disadvantaged context, suddenly collapses and is taken away in an ambulance. At the hospital, a doctor informs him that he has inoperable lung cancer and still has a couple of years to live.

So, having been introduced to this world through a policeman friend of his who wanted to find a methamphetamine laboratory, due to … Various detailed reasons that I am not here to tell you, I do not want to summarize an episode of one hour and twenty …

Walter, along with Jesse Pinkman (his former student of him), also becomes an active producer of methamphetamine.

So, this was Walter White.

Who is Heisenberg?

Well, a nice change from before.

The methamphetamine that Walter produces begins to dominate the drug market. While Walter was initially picky about the use of violence, he gradually comes to see it as a necessity and eventually develops into him a ruthless drug lord motivated largely by vanity, ego and greed.

So does Walter White become a total villain by becoming Heisenberg?

… Not really. Barring any analysis that can be done on his behavior, in the end Walter White’s transformation into Heisenberg is given by one who is already born as a frustrated man.

(Season 4, Episode 6 – Cornered)

“No, of course you don’t know who you’re talking to, so now I’ll explain how things are. I’m not in danger, Skyler. I am the danger. A man opens the door and they shoot him and do you think that man could be me? No. I am the man who knocks! ”

In this iconic and very famous scene, Walter is in the middle of his path of corruption , this being the fourth season. He feels insulted by what his wife Skyler is telling him, which is that he is “in danger”. Walter tells her that he does not know who he is talking to: he wants to show as much as possible that he is no longer what he was her husband and claims his nature as a “Heisenberg” that he has built.

“A man opens the door and they shoot him, do you think that man could be me? No. I am the man who knocks! ”

This sentence is very clear. We have seen that Walter White has always been a person with a routine marked by constant inconvenience: from the workplace to the family. I think the official fan-wiki description about the series can describe what Walter felt (when he was still “White”) better than me:

“ It is clear from the start that Walter is suffering from a midlife crisis. He feels downcast, tired, bypassed, cheated, emasculated, exploited and dissatisfied.

Even the field in which he has the most skill, chemistry, falls into the void of his disrespectful and apathetic students. Even before his diagnosis, Walter felt like a failure, unable to adequately provide for his family and fulfill the role that American society expects of him.

The news of his terminal lung cancer leaves Walter numb and shows almost no emotion when he learns it, as if he were already dead. Learning that his life will be unexpectedly cut off, coupled with the knowledge that he will leave his already bankrupt family, is the last slap in the face, the last humiliating insult that life can inflict. “

So, as Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Duke Francesco Ferdinando is described each time, his cancer was just the last straw for a man already predisposed to failure. This is also the reason why so he got into the drug business relatively quickly, compared to what a person of true sound principles would take to make a decision whether to continue what Jesse introduced him to or not.

So Heisenberg actually, along with all of his negative traits, is just Walt’s frustration that ultimately came to the surface, making him the cruel kingpin who develops and descends more and more into depravity in subsequent seasons: Walter White’s is not, therefore, sudden corruption but the result of a constructed context to make him a frustrated person, even without falling into total disastrous / dramatic and a series of situations that have challenged his moral, both when he was supposed to be “Walter” and when he was supposed to be “Heisenberg”.

(Season 4, Episode 6 – Cornered)

A Walter is presented with the decision that he can admit to his wife that he is indeed in danger, because minutes earlier he demonstrated a moment weakness, I think also obvious. But Walter rejects this statement , claiming the nature for which he wants to be recognized, that of Heisenberg. But in general his entire conflictual relationship with Skyler is the perfect demonstration of the moral conflicts of him as “Walter Hartwell White.”

(Season 5, episode 14 – Ozymandias)

Since his brother-in-law is part of the police and the latter is captured by a collaborator of Walter (I don’t know exactly the role of the character of “Jack” in the plot nor what relationship he has with Walter, so forgive me the small inaccuracies), even if by the end of the first season he has already started his journey as Heisenberg, this did not mean further moments of upheaval, weakness or humanity for Walt: He keeps begging for the life of Hank (his brother-in-law), but Hank refuses to cooperate and is killed. Walter is horrified; he falls to his knees and then falls to the ground on his side, crying.

After these situations, in fact, Walter in the series demonstrates under the name of Heisenberg who he always wanted to be , or rather “not the one who gets shot in front of the door”: hence the drug business, so he seems to be talented, for Walter it is a solution to this inner malaise he has had for his entire life and the horrible acts he does over the course of the series we can consider them as the outlet of a frustration that has accumulated for decades.

And therefore, given this continuous contrast between these two identities that blend inconsistently in Walter’s person, we have what everyone considers the anti-hero par excellence, the perfect anti-hero.

But, in any case, even if you can do all the psychological analyzes of the character we want for this man …

![]()

(And, I add, the one above is one of the acts that destroyed Jesse the most mentally, it seems)

(The one on the left is the woman’s son, Brock, who died for the same reason as his mother)

![]()

In short, we can understand as much as we want, by analyzing his personality … But he is still “The Danger”.

I thought it was fair to talk about Walter White, talking about anti-heroes. He is considered one of the greatest of all time and makes you understand perfectly what it means to have a well-written character who can be adored at the same time: without victimization, without mercy for him.

“Understanding” means understanding the reasons why a certain act was done, but don’t necessarily say it’s right, that what we have in front of it is actually a good person, or even just someone “likeable”.

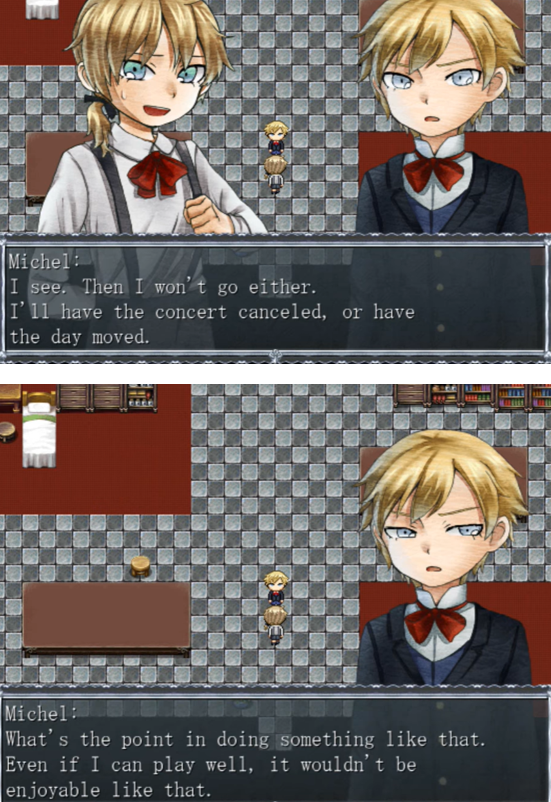

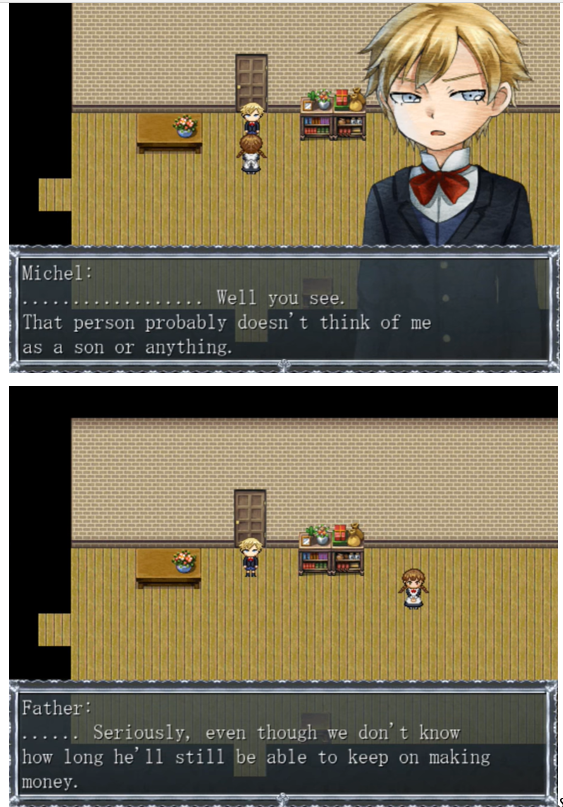

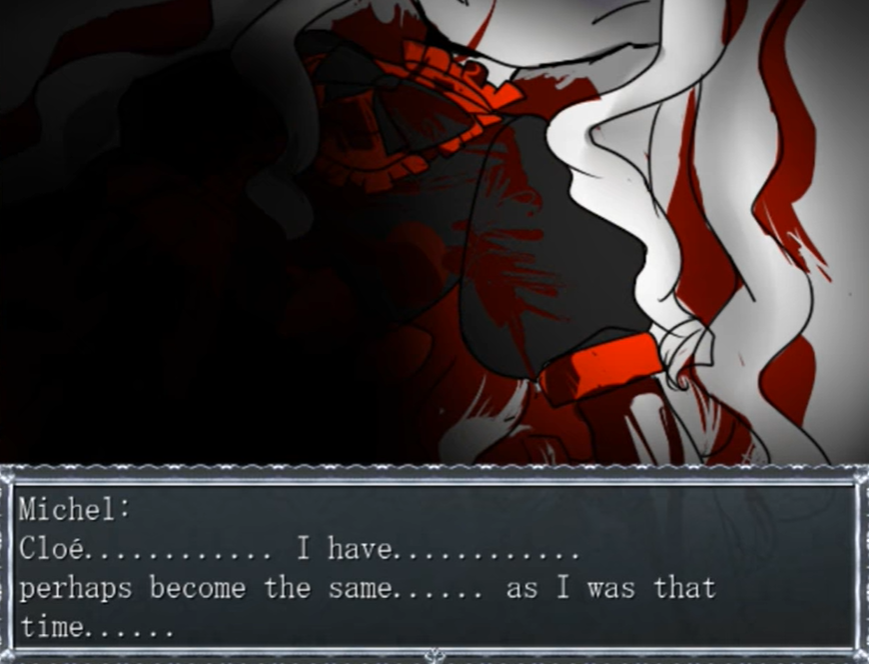

Michel D’Alembert – The positive path of a kid at risk.

Let’s go to the little boy in the center, who looks a bit disfigured next to the two big men James Gandolfini and Bryan Cranston. His analysis will also be shorter than the other two characters, given that his psychology has been sufficiently analyzed in the appendix to the article on Cloé’s Requiem. I wanted to talk about Michel again from the point of his probable “justification” mainly because the comment I put three times in this article comes from Cloé’s Requiem: Con Amore, an extra version of a game that certainly has one of the more complex characters that I know well.

Then:

Michel, already from his past, is always considered a childish boy.

This infantility is visible: therefore, right from the start, we can guess that Michel’s immaturity as said by the other characters is not based only on chatter and above all it is TRUE. It has very clear demonstrations, including not being ready to enter the adult world, where everything was profit in those days.

We can see this from the character of Pierre, the more mature twin, who constantly condemns Michel.

Michel kills the maid Charlotte for a wrong, and later her father for the same reason, given his obvious propensity and risk of psychopathy.

he He then has a moment of delirium and, running away from home, he begins what is interpreted as a therapy path at Cloé’s home.

Here Michel, in addition to knowing the story of her girlfriend, begins to have a distorted view of her.

And when this vision is betrayed he has a second delusion.

“The Antihero is an individual who – from the very beginning of events – has no fear of showing the darker side of his personality . The salient traits of his personality can range in any direction, from selfishness to violence, from selfishness to shyness, from fanaticism to submission to reaching and exasperating every other human characteristic. “

But his positive path towards redemption along with what I consider therapy starts here: he reads Cloé’s diary, which disillusiones him with his previous convictions.

He realizes what he has done and, even though Cloé does not understand why he is doing it, Michel apologizes to her.

Michel has real faults , sick and twisted visions of the people whosurround it, and for this it has paid the consequences. It has done so with so much inner suffering, along with the risk of death at every corner because of the cursed house.

And, most importantly, the fact that his father was exploiting him for money is never, ever mentioned, and his inner suffering never becomes an excuse. That detail gives us he is told only to know the story of this character and why he ran away from home. It is as if for everything he did he had to go through those obstacles and that pain.

In the end of the game, therefore at the end of his growth path, Michel does not stay at Cloè’s house, hidden and unaware of her faults.

A player, however, can always think about everything Michel did before this final state. Michel is never a victim. He has always been someone who hurted people (or risked to do it): from murder to possession. For the entire game we have to deal with an ambiguous character, even if we subsequently know that he suffered.

“Understanding” means understanding the reasons why a certain act was done, but not necessarily saying that it is right, that what we have in front of us is actually a good person, or even just someone ” likeable ”.

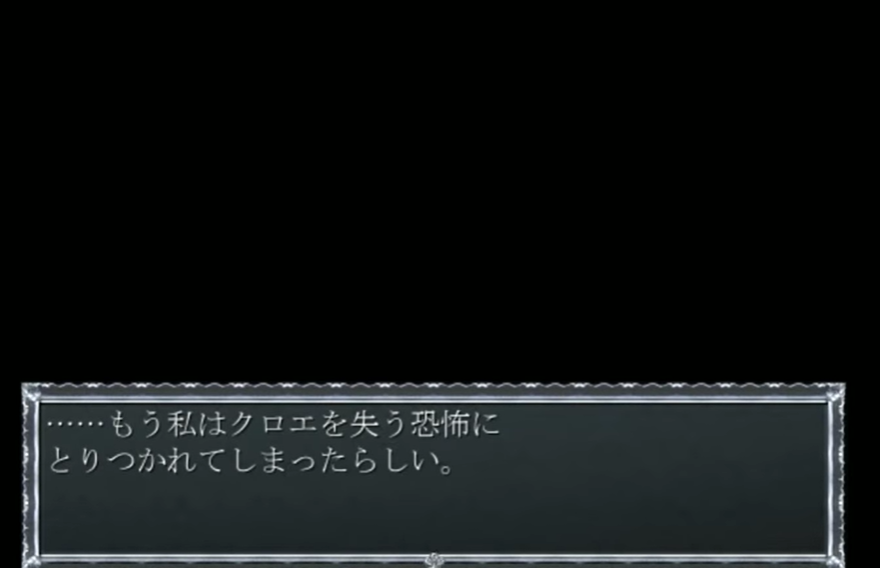

(Michel, even after apologizing, still feels guilty about the distorted vision he had of Cloé)

(Michel has a constant fear of returning to the way he was before, a dangerous person for himself and for others)

Michel certainly had a different path than Walter’s, he is actually “redeemable” even in our heads compared to him …

But because Michel himself has had a path of growth , which can make us think of him as a person who has managed to grow in the course of his difficult life.

Michel also matches these descriptions, therefore, even if we have a different type of path.

Our latest case, which I will mention several times in this article, is Tony Soprano, star of the TV series “The Sopranos”.

“Hehe, I recommended this to him!”

“Hehe, I recommended this to him!”

“Here, in fact, I haven’t seen the series … Come here for a moment!”

“Here, in fact, I haven’t seen the series … Come here for a moment!”

TONY SOPRANO – A double view for a mafia boss

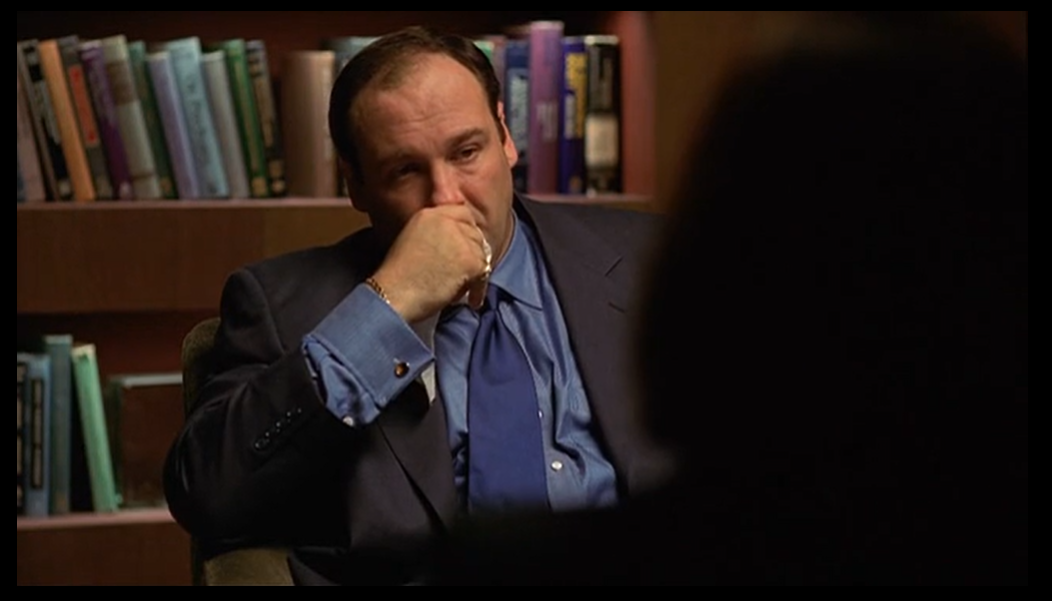

And only for this part about Tony Soprano here I am ready to do a little intervention! I want to be absolutely honest with the fans of this historic television series: I only saw a few episodes to take an exam; I have absolutely not seen everything about the world of “The Sopranos” and this is one of the main reasons why I will limit myself to commenting, also considering this case study as a way to close this parenthesis on the good examples of the characters, only one scene in particular that can summarize the our intentions on this article.

For those who read this article and do not have had the opportunity to enter the world of TV series, you should know that one of the strong points of “The Sopranos” is to tell the daily life of an Italian-American mafia boss . By daily life we mean both the problems he has to face with his subordinates and the anecdotes of family life.

You should know that the first episode immediately focuses on the fact that Tony goes to a psychiatrist for the first time, where he begins to explain to us that had a panic attack, with fainting attached, when he discovered that the family of ducks, who had settled in the swimming pool of his house, emigrated.

There will be more anecdotes from the psychiatrist in which the recurring symbol of the duck keeps returning, for example in Tony’s dreams, and it won’t take long for the doctor to discover that that image is as recurring as the man’s fear of losing his mind. His family making him cry during therapy.

To see this scene just go to the minute 0:51:28, first episode

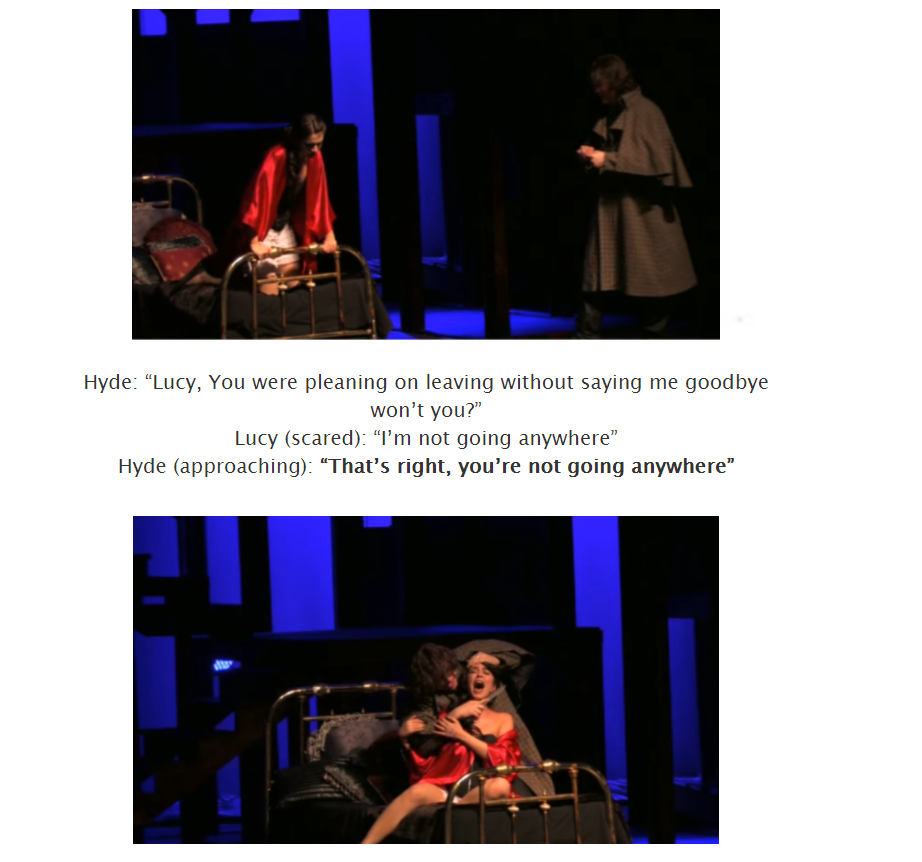

Not even five episodes later we have a scene like this!

Episode 5 , from 45.54 min you can start watching this long, anxious scene

There are two things that struck me while strangling Febby Petrulio, or maybe three.

The first, the most “obvious”, is how in the scene you stop to frame the belt that tightens on the throat of the victim. In short, we really insist a lot.

But let’s get to the important things:

- The shot has something disturbing because even the camera is in a position where it seems to be dominated by Tony, that is, we ourselves as spectators identify with the victim who is suffocating.

- A few seconds ago this poor man had said something like this: the moment he found him the night before “he didn’t shoot him because he was taking his daughter to college”, he thought Tony was another person .

And after the unfortunate man has left us his feathers, what happens? First you hear a rising sound, an echo, and then a flock of emigrating ducks is shown that Tony stares at, framed from top to bottom …

Surely the ducks that are heard in the background is a very important link in the context of the series, but even seeing this scene out of its context we can see the difference in the use of the shots on the character and therefore the change in our perception towards him. .

From below and then from above, we are above him, we can judge him because the character becomes small on the stage. From the veins, the effort and the expression of anger that almost frightens us, following the calm shown for those who have been carrying out these activities for a long period of time, there is immediately after this scene in which Tony “is judged from above” and he can only contemplate.

I want to consider another element in this scene …

I really want to show you how a simple comparison of images is enough to unleash certain emotions or sensations in us!

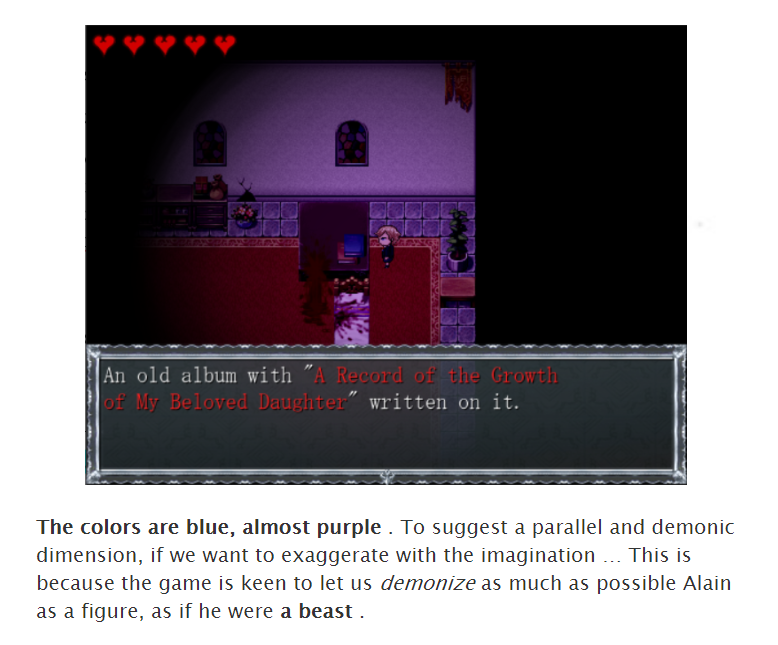

Do you remember that I had made a similar example, from the most negative point of view, in Cloé’s Requiem?

Without any commentary, dialogues, words, phrases but simply observing the change from one moment before to the next in a single scene alone 2 minutes, assigning a meaning at this passing of time we can change our perception of the character and our impression of him confuses us, keeps us tense and makes us reflect.

Returning to Ele …

So, in addition to what you consider a fan’s thoughts on Cloé’s Requiem, we also analyzed characters that are part of cult series, Tony Soprano and Walter White are often defined as among the best characters of all time … And indeed, all these beautiful characters respect this definition:

“”Understand “means to understand the reasons why a certain act was done, but not necessarily to say that it is right, that the one we have in front of us is actually a good person, or even just someone “likeable”. A character we understand is a character that the public is not forced to redeem, but who remains from the complex and logical psychology in his actions.

Let’s take one of the characters we have previously analyzed, does it reflect this definition?

Aubrey is a very childish girl who has developed violent outbursts and a propensity for aggression. This is because she is still grieved by two griefs she has had to endure.

But how does the game put you down this pain, which is expressed by Aubrey with unwarranted violence towards others?

So, ultimately, Omocat wanted to tell us that Aubrey hasn’t done anything wrong and that the problem is “the people” who “want her to be bad.” In short, “it’s always someone else’s fault” .

Small problem. Nobody wanted Aubrey to be reduced to this state. Aubrey as a child she was not bullied, much less hated by anyone: she was not even defined as a weak person. Aubrey self-destructed herself, she did everything, she should mostly blame herself!

We will explore this theme later, but …

Here there is no moral conflict for the player. Anyone who sees this scene totally changes their mind about Aubrey and in the end she is as good as everyone else. Violence becomes a her being “a little aggressive” and in the end they are all happy and content.

A character we understand is a character that the public is not forced to redeem, but who remains from the complex and logical psychology in their actions.

Crooooss

So this is not humanity. This is a simple crybaby, who wants to win over arguments that are dead and buried years ago, but only because she does painful faces, almost beats us with tears and is objectively a pussy crazy, we justify it.

Let’s compare it with a cult …

As we have already pointed out Tony Soprano is a mafia boss. From here we can understand that he does almost every kind of atrocity: I don’t think I have to explain what the mafia does.

But in any case, an everyday reality is also presented. We have the same boss that we find mercilessly killing people having a panic attack, and in general … Just being a man, with clinical problems from his past, but not for this the actions of he are justified. Tony is still part of the mafia, but at the same time he has a family he cares about, he has problems that unfortunately he has to live with …

But he never hesitated to shoot someone. He never hesitates to do his job, nor does he cry over it, when he is introduced to us. When we find out about his past we have the reasons for his anxiety about him, how he got into the mafia …

We only have reasons, not justifications.

There is, therefore, a real EMOTIONAL CONFLICT to judge him , or to put him on a moral spectrum instantly. Because it is born as negative, even if it demonstrates the so-called “humanity” that we all seek.

But why am I looking for “conflict” so much?

“Why, what a surprise, storytelling is done with conflict! If there is no clash between two or more elements, what development must there be? ”

“Why, what a surprise, storytelling is done with conflict! If there is no clash between two or more elements, what development must there be? ”

And like conflicts, since today’s stories all want to pretend to be character driven… People look for conflict in characters. So internal conflicts, to be passionate about, to debate in order to come up with stimulating speeches, because when you want to analyze the reference work, this is what a fandom does …

“Ahh, you’re right. This thing has the philosophical meaning of –͚̓-͎̑͡ͅ-̭͎͗̀-̼̝̂̑-̞̗̿̾.”

“This girl doesn’t understand anything, but she doesn’t see the conformation of Omori’s maps? She blatantly says –͚̓-͎̑͡ͅ-̭͎͗̀-̼̝̂̑-̞̗̿̾!”

“She has never played Midnight Train in my opinion.”

“This double side, this double value and conflict that you praise so much with … What’s his name? Tony? It’s here too! Criminals but good-hearted all the same!”

“She talks about Tony Soprano, c’mon … She just wants to give herself a tone because her sister tells her all about this old stuff, and she’s salty because the others are more popular than her …”

“…”

“…”

“… Okay, I’ll give you an example with something your philosopher’s cerebellums might appreciate, since Tony Soprano doesn’t interest you.”

“… Okay, I’ll give you an example with something your philosopher’s cerebellums might appreciate, since Tony Soprano doesn’t interest you.”

…

“Have you seen Frozen?”

“Have you seen Frozen?”

“Ah-ha. The most innovative Disney classic I’ve ever seen.”

“Ah-ha. The most innovative Disney classic I’ve ever seen.”

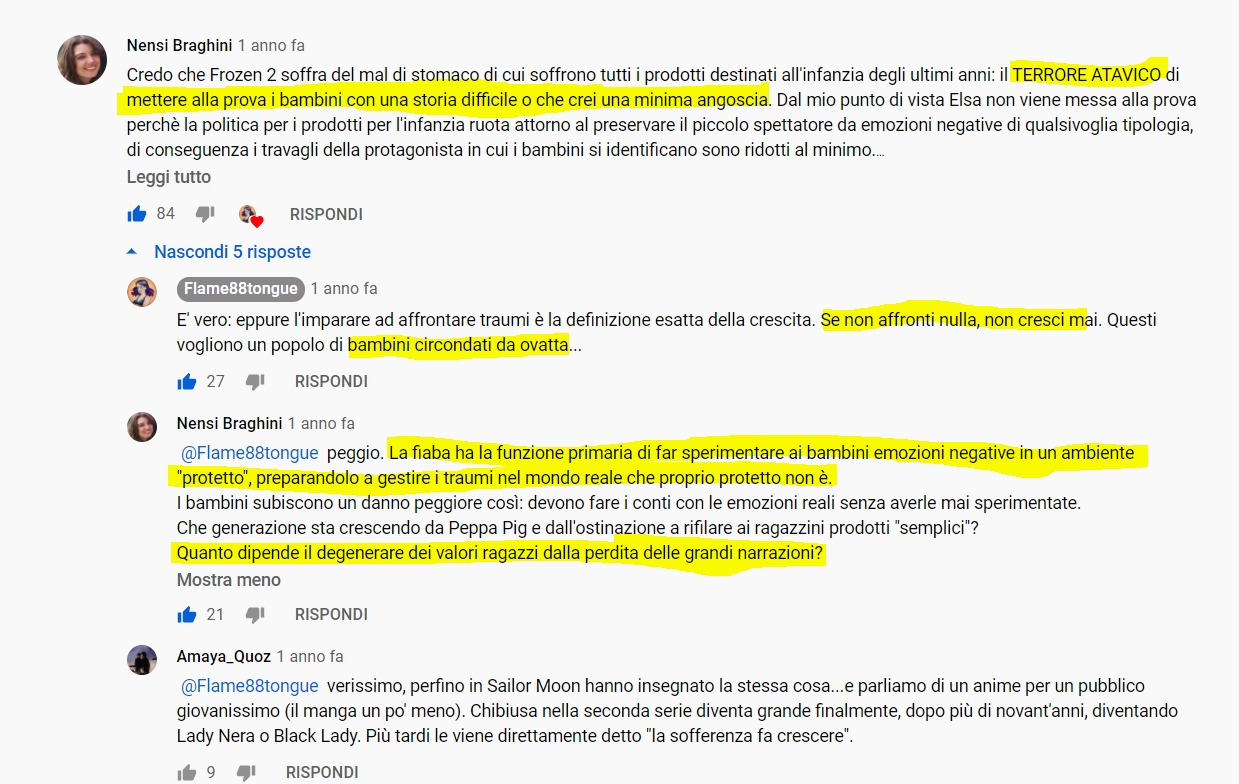

… I leave you to this screenshot. It is from the fans of a youtuber who criticizes animated films on Youtube: Flame88Tongue. She has heavily criticized Frozen in general, and her fans of hers have come up with a very interesting speech.

“There is an atavic terror to test children with a difficult story, or something that creates a little bit of anguish.”

“That’s right, if you don’t face anything, you never grow… These people want children to be surrounded by wadding”

“Fairy tales has the primary function to make children experiment negative emotions in a “protected” ambient, to prepare them to the traumas of real world, that isn’t really protected. (…) How much the loss of moral values depends from the loss of big narrations?”

The video focuses mainly on how Elsa’s character is treated. It has many similarities to the cases we have today: horrible person, victimized… So good, for some reason.

This need to make Elsa a victim conditioned the writing of the entire first film: the screenwriters, to make this BITCH true, had to rewrite the film from scratch. Elsa was supposed to be a villain, Let It Go was a song for the villain.

But no, you can’t have a bad person. All bad people have actually suffered, and they can be helped or fixed to make them the good people they really are! We talk a lot about “cruel world” and the like, to be a little edgy and pseudo-realists …

And then in the works of fiction we let ourselves be enchanted by these childish ideas?

Guys, we were confronted with children surrounded by wadding.

I despise the definition of “special snowflake” in English with all my soul. It is often used by ignorant people who, for one reason or another, feel they are minimizing the problems of others, insulting them in this vulgar way.

But … In this case I want to use it, I think it’s worth it.

This evil no longer seems to be relegated only to products intended for children …

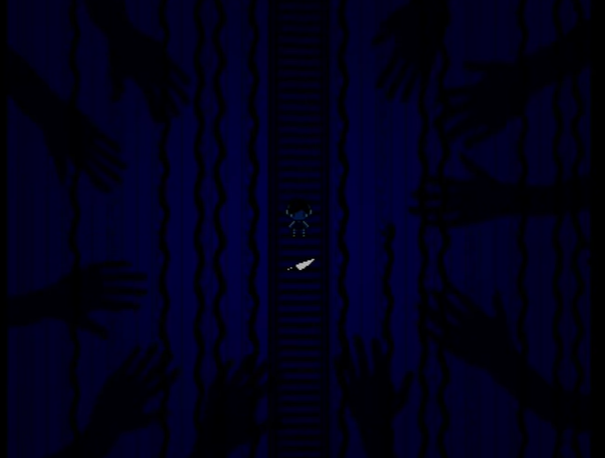

What I notice in many recent creative works is that now we are no longer looking for something seriously raw or distressing , even in the genre that should be the cornerstone of these two sensations: horror.

We, the audience, have become special children who see the slightest struggle and want to write us a hell of a treaty. Not only because we are only good at talking, but because as idiots we let ourselves be moved by scenes that in reality then they have no consequence. We never see the weight of the actions done, or even just the weight of the words.

Because in the end there is never a real conflict, not even when potentially terrible or ambiguous things are done or said, “turning points” no longer exist. There is nothing that really marks, for example, the relationship between two characters, there is nothing that makes it change permanently for the better …

(Cloé’s Requiem, True Ending)

Or worse.

(Breaking Bad, S05 EP.12)

The value of the basic fictional work has been lost. The CONFLICT to be solved in order to have a resolution. Or the conflicts are so futile or really reduced to a minimum as to make the viewer always feel safe, with resolutions thrown in, idiotic, illogical, tacky and level of a soap opera at the level of useless drama. We spend our breaths on works that do what is the minimum for the work of fiction.

(Really, the confrontation with Basil had to be one of the main points in the game, not in the conclusion just to solve all the plot points. The single scene has potential, albeit with symbols seen, revised and overwhelmed, but compared with all the plot that exists, it is a show for its own sake, which is also illogical with plot elements.)

And I have a hypothesis on why all this.

Because we don’t want to recognize ourselves in any problem that could affect us too closely. Why us; public, developers or anyone… We always want to feel understood . Always. This is why we like worlds where everyone is a victim, where everyone can be “settled” with two words of comfort. We secretly have that attitude of “maybe life would work out this way”.

With “special snowflakes” therefore, in our case, I mean that we have reduced ourselves to small waffles . We want someone or something who always understands our problems, even if in some cases there is nothing to understand. And we do this with the phrases “there will be a reason why he is doing this!” , which actually translates to “there will be something that justifies these behaviors, because I cannot conceive that some impulses and jerks are in the human nature, which is not only complex when I want it, but is complex in any case, even with its inexplicable negativity “.

Instead in these types of works today no one is actually a bad person. We hide with the excuse that “we all have weaknesses and facets” to hide a gooey goodness of people affected only by external negative stimuli, which in reality they never have any fault.

This is why any attempt at conflict is futile.

Because in the end we all have weaknesses, so we always deserve to be understood and we must never change.

“You had an expression of pain.

The performance didn’t seem funny at all. “

Because in the end it is always someone else’s fault for our every negative aspect.

Because in the end our feelings, as long as they are good, can also be strong enough to commit immoral acts.

And as long as we suffer, any kind of our impulse or impulse, even if harmful to others is fine, so it will always be someone else’s fault .

Because we always deserve love, we always deserve to be understood and loved.

Do you want to tell me what the hell messages are from today’s creatives? Will you tell me what Horror RPGs are becoming and what modern fiction is becoming in general?

Speaking of the case of Horror RPGs, given that this site talks about this particular current and how it is falling to its demise…

I really want to show you how this current worked long ago.

On this site there are various articles in the “Back To The Future” section, where we talk about games that have been real cult of the genre.

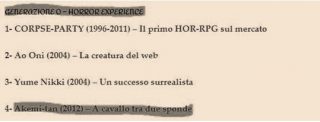

Now let’s see what these titles give us. One by one.

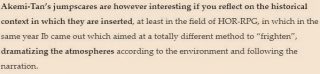

Corpse Party – 1996.

It has practically given us the basics, even if it now moves away from what can be defined as a “classic Horror RPG”. Great representative of Generation 0, the CORPSE-PARTY (yes, I speak of it as a literary classic, because I consider this too history!) By Makoto Kedouin was the OG, the one who started so many projects on the basis of one thing: the contact and experience made by the player.

This was increasingly developed with Ao Oni , eventually reaching its peak with Yume Nikki.

Here the player experienced the real horror experience on their own skin .

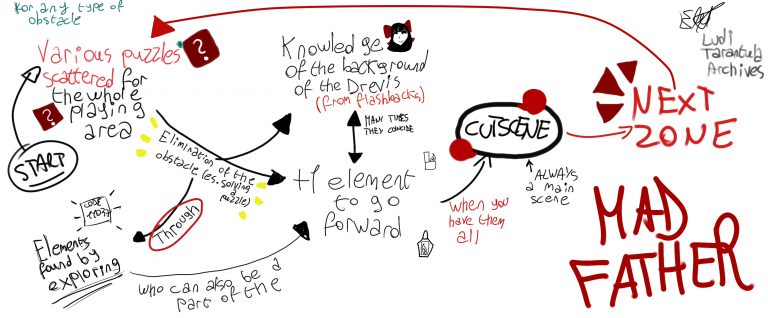

Mad Father – 2012.

Generation 1: The Character Drama.

Sen wanted to try more at the level of similarity with passive fiction, and managed to prove that he was a creator capable of making entertainment . The story, in the original Mad Father, did not demand or force particular depths. Sen’s Mad Father began shaping what would later be completed by …

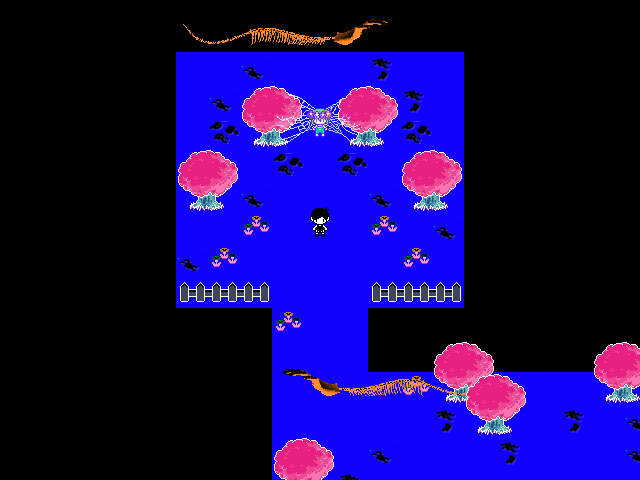

Mogeko Castle (Remake) – 2014.

End of Generation 1.

Mogeko Castle is a clear parody of what has been built during the generation in which it stands. It has brought variety to the Horror RPG genre, risking the gameplay a little to simple exploration, giving even more importance to the inspiration of the passive opera at its best, with many different registers to form a multifaceted work . So, Funamusea’s Mogeko Castle adapted to the best of what Sen had started, with a captivating product to the stars, and content to be stripped away (from character descriptions to content made by the author herself – such as those of the “Girl with Lifeless Eyes “And the” Girl with Flashy Hair “), so as to try to take the Horror RPG genre out of its niche, to take it to something bigger.

Do you see how much these titles have given us? Some are really “simple” and none of them have “changed the international gaming landscape”. No one has ever spent such big words on it. Because they only did what their genre says: they were Horror RPGs.

We were just scared, had fun and expected nothing more than to get our hands on other “games similar to Ib”. We enjoyed it, when we were younger we didn’t sleep at night …

“Has anyone ever been afraid that Aya’s father would show up before you in the dark? Are you sure?”

“Has anyone ever been afraid that Aya’s father would show up before you in the dark? Are you sure?”

“… No? ”

“… No? ”

“Oh. Ahaha, children are so dumb!”

“Oh. Ahaha, children are so dumb!”

At certain times there was no need for Outlast’s big jumpscare, when it came out in those years along with its DLCs. No, we wanted to experience serious and very cool restlessness. Of course, we talked about the characters, we had innocent debates and everything: a great case was that of Ellen, who shocked the entire audience who watched gameplay or played The Witch’s House …

But the first thing we did was entertain ourselves , because the writers knew what the hell they were doing, and they knew they had to ENTERTAIN people.

Now … Now what do we have? What do the authors give us today?

(Intervista di Omocat a IGN)

(“Midnight Train” 2019 title from the author Lydia. We will talk about it later)

They give us their disappointments; how they cope with their disappointments. They communicate to the public their need to comfort themselves . They don’t care about us anymore. RPG Horror today has become just a label to be applied to causal titles from spoiled children who want to express how much they feel the need to feel “understood and important” because they are frustrated with their life and the world.

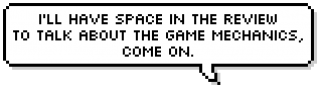

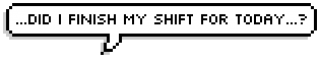

“… Those were my notes. Didn’t you edit them either, or anything? Hell, we’re not here to personally insult, I mean you had to put it down another way …”

“… Those were my notes. Didn’t you edit them either, or anything? Hell, we’re not here to personally insult, I mean you had to put it down another way …”

“Listen … I had to say it. I couldn’t find any other words.”

“Listen … I had to say it. I couldn’t find any other words.”

“…”

“…”

“Who the hell do you think you are?”

“Who the hell do you think you are?”

“…”

“…”

Yes, I said a really generic and bad phrase. On the part of developers, these kinds of slips just don’t have to be there. We risk making the figure of someone who simply eats his hands to the success of others.

But … Really, I’m not going to insult individual authors here. It’s a problem that RPG Horror in general has been carrying for a long time. And in my opinion, is the one that leaves it a bit in the niche compared to other video game subgenres , what makes it undervalued as a genre to be totally fixated on and that has kept the current in “simple and adorable indie games that were fashionable in 2012 and now boh”.

The videogame has always been compared to many other different fictional works. From a technical or narrative point of view. In some cases, I take Red Dead Redemption 2, many games manage according to some to stand up to cinematographic works; be it blockbuster or B-Movie. On this, however, the video game is still evolving and I know it well.

Now, speaking of a relatively recent game, I really want to make you understand with a case study, with what is a case of creative ingenuity, all the good speech I made. We really compare a Horror RPG today with a character driven work of an industry that existed before that of the cinema, which today alas is suffering various problems.

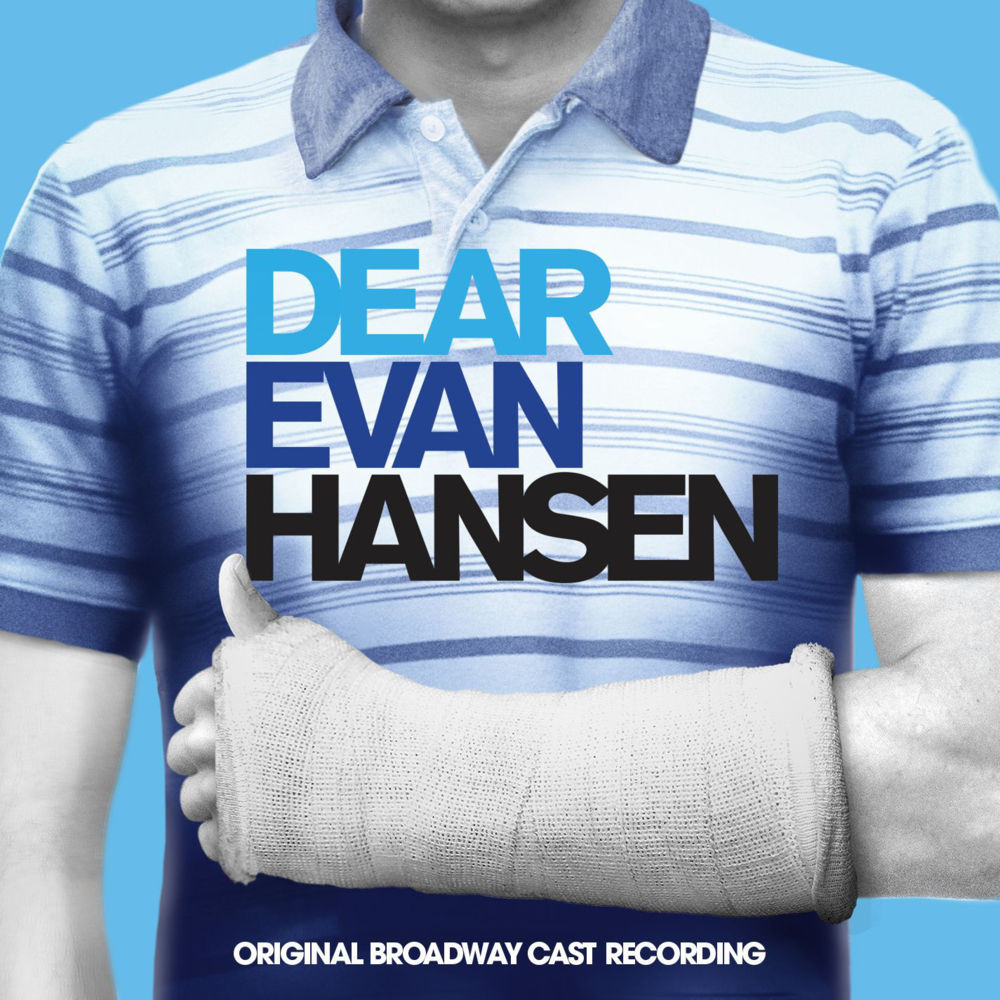

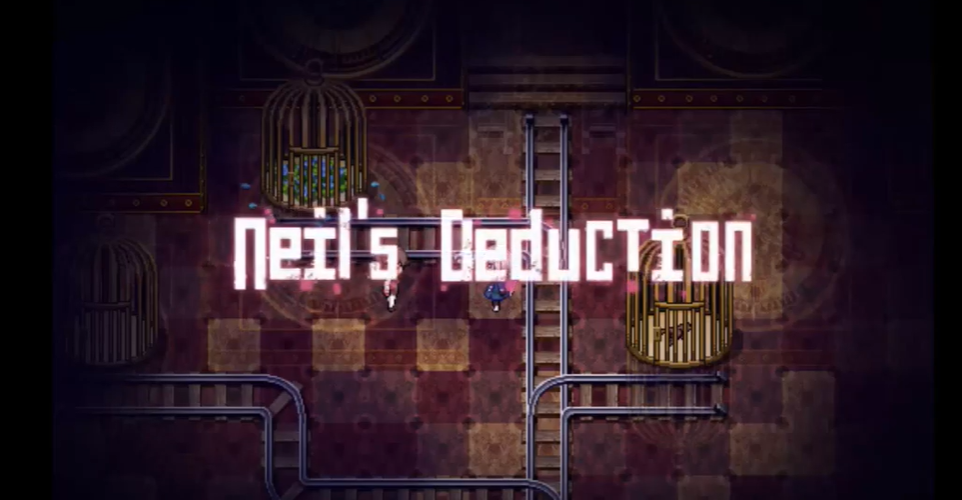

“Dear Neil Lawton, this is gonna be a good day and here’s why.”

-Dear Evan Hansen and Midnight Train on the problematic protagonists-

The former is an adventure RPG released in 2019. The latter is a musical with a drama story, which premiered in Washington in 2015.

I played Midnight Train several times with my sister, because many times we enjoy playing things we hate since we are masochists.

“You count this pastime as… When with friends you see“ The Room ”by Tommy Wiseau!”

“You count this pastime as… When with friends you see“ The Room ”by Tommy Wiseau!”

Dear Evan Hansen … I haven’t even seen it all, nor heard all the songs. I will know 3 or 4.

“What? You haven’t even seen it and pretend to compare it to-”

“What? You haven’t even seen it and pretend to compare it to-”

“… I can’t take it anymore… Are you still here, you…?”

“… I can’t take it anymore… Are you still here, you…?”

I was saying … I don’t know the whole story of Dear Evan Hansen, I know some fragments and I know few songs, so I can’t objectively judge it as a product …

Why, however, I want to confront them anyway?

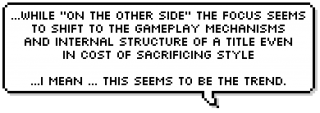

Actually I want to talk about a very, very simple theme, which in the musical I can circumcise to just the song “Good For You”, and in the game I can circumcise to Neil’s behavior in Chapter 4 of the game.