And precisely because it is coming, that activity that we would all dream of doing at least once in our life returns: listening to stories in front of the fireplace, especially when they have to do with the world of mystery!

So, you will have understood what I am talking about, of course, about storytelling in the context of Horror RPGs! Well, after all, it was also the title of the article. Yup.

What to say, we started this year’s season with a lot of premises and discussions but finally we will be able to begin to resume together the slightly more theoretical approaches, in the article on Purgatory I had badly run away … I was looking forward to this one!

What are the premises for this article?

To begin with, the advice I propose is that I am not a scholar of some kind of videogame storytelling class. Everything I will say here is based only on the observation I had the opportunity to make during my experience with Horror RPGs.

What I noticed in general, even though I’m ignorant on the subject, was that in the world of video games the narration has never been an element for which the media has distinguished itself and the complexity of a plot is also scarcely considered in a proper manner, not to mention the issue of multiple endings. It is not only in the context of RPG Horror or in Japanese titles such as the various visual novels and route models, many Western titles also seem to take advantage of this method. I could mention titles like Detroit: Become Human which are based on numerous endings depending on the game choices. Many have considered it as an admirable operation and to be commended, I can understand why, but. There is a but.

It seems to me a “too comfortable” move. What I ask myself is how much it is worth staggering the responsibility of entrusting the player with the progress of a story, I would see it as an excuse to never make a final decision. Leaving aside the cases where the story is linear and technically only an ending is right, I take advantage of this premise to state that the theme of the endings is the last thing we will worry about in this article .

I know it had to be said, because it is now one of the key features for which RPG Horror is known, indeed, one of the few formalities in the narrative field for which the genre is recognized.

By making a short historical re-cap we try to remember one of the key elements of this genre: the clues inherent to the storyline are discovered during the exploratory phase which often distances itself from the part of a story in which there are cutscenes. Good.

Then we will remember that Mad Father introduced and made the public recognize the basics of linear narration in which the discovery of the clues of a story are strictly limited to a precise context. Let us remember, perfectly introduced the theme of linear narration in an area as wide as the videogame one in which everything is in the hands of the player.

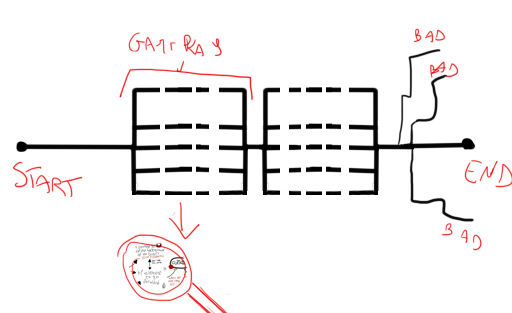

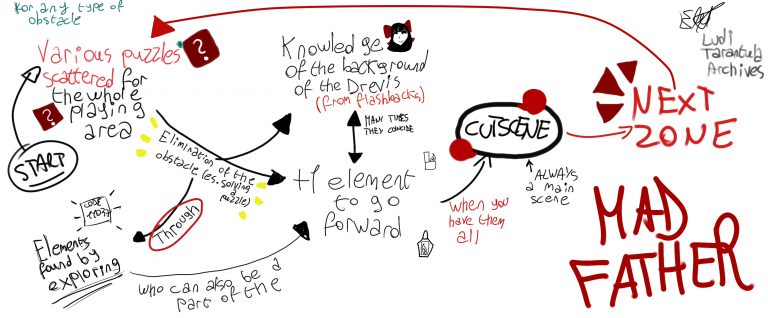

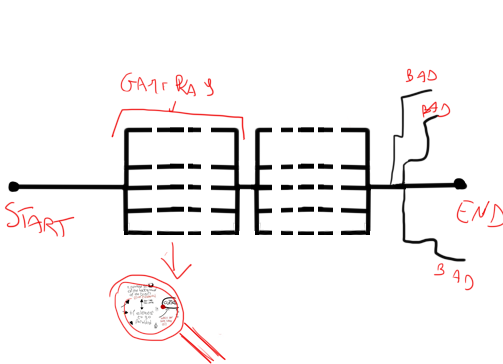

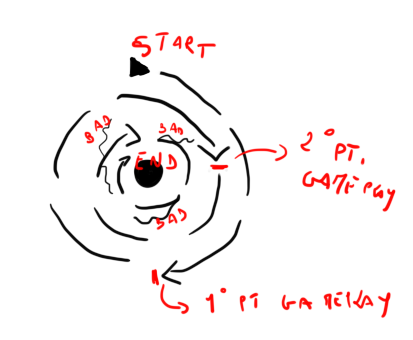

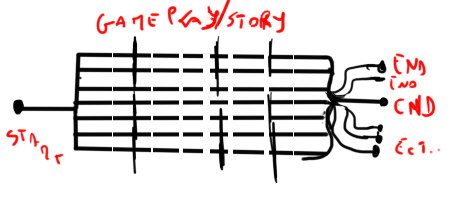

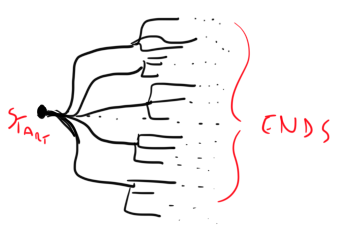

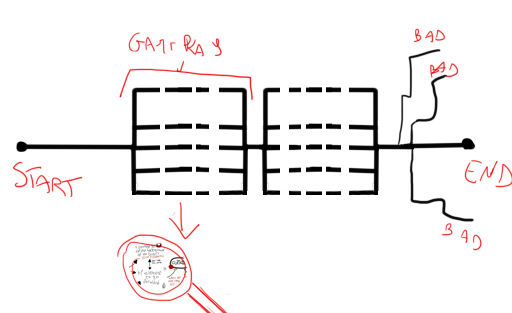

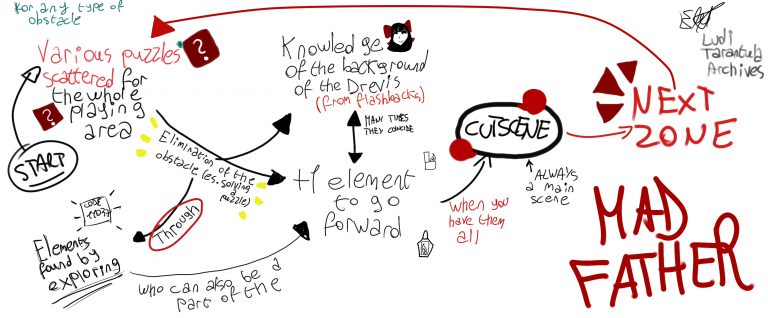

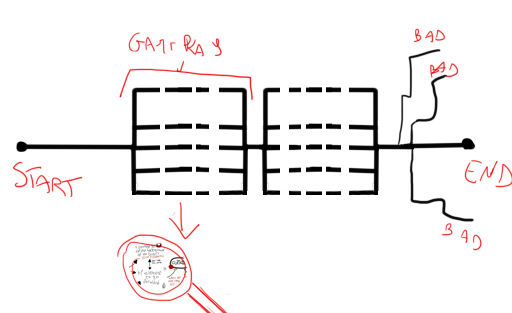

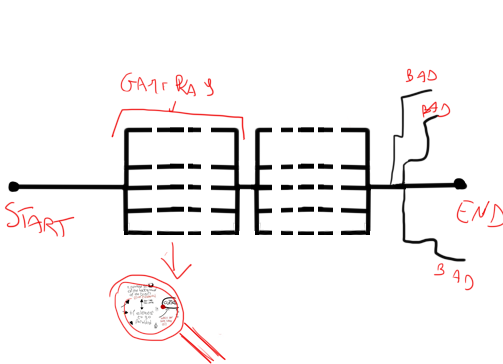

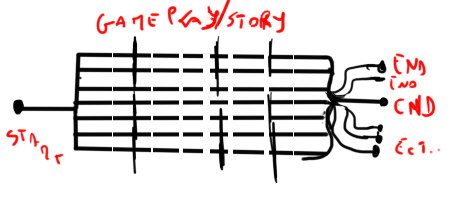

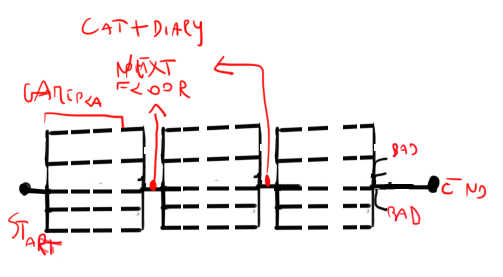

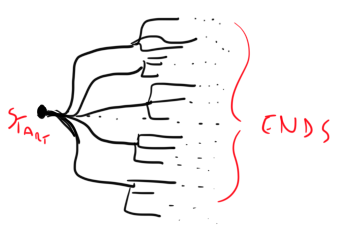

Let’s review this concept for a moment, I leave you this outline here.

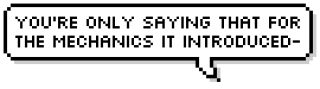

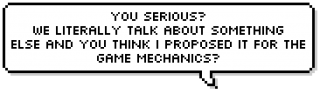

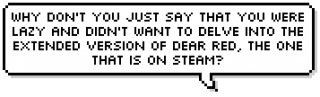

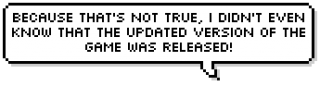

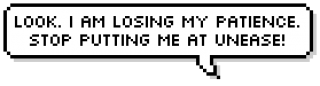

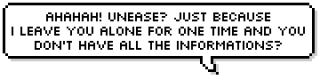

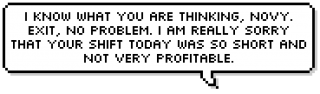

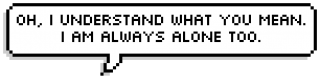

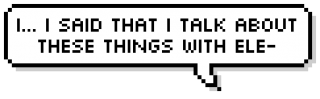

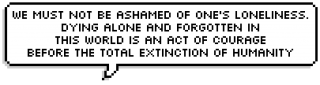

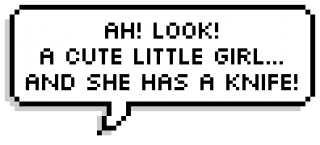

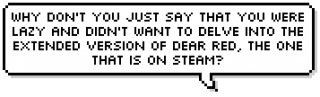

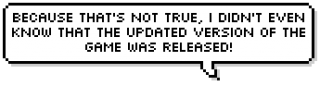

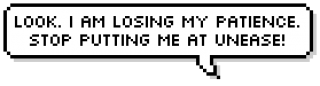

… Ahem.

Here, good young lady, calmly go back to work.

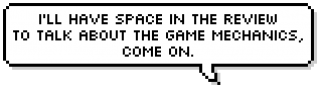

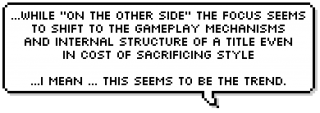

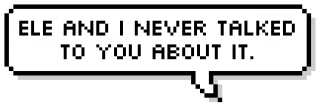

So, yes, our assistant has speeded things up a bit too much, we’ll deal with the three screens later …

Rather let’s see the scheme he proposes before concluding the speech on Mad Father.

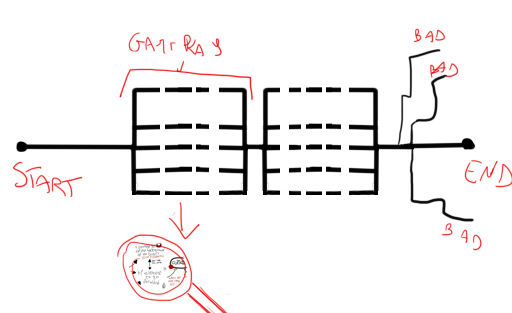

We have the unique narrative line, the parallel dotted lines you see are all those clues and flashbacks that are scattered throughout the game, but then as you can see they all come back to a single narrative line that never stops being only one and stable and based on the cause-effect relationship [1] , a feature that is already distinguished by the fact that the gameplay phase the level of action and understanding of the story is, however, different from the “big scenes” that carry on the plot. And this goes on until the final act, to be exact the reaching of the breakpoint in which the endings branch out only in the context of the conclusive climax, these lines as you can see go well with the scheme on the free gameplay that Ele had done in the article dedicated to Mad Father.

……So….Here’s my scheme again.

As you can see I marked the endings with thinner lines to indicate the little impact on the main narrative line, the game makes you understand very well the chosen path. The various “bad ends” are different consequences to types of events, do not distort the personality of the characters.

At this point you must have understood one thing: the narration I am referring to refers only to the text . The text is the game itself and is read, understood and interpreted just as one reads a sentence.

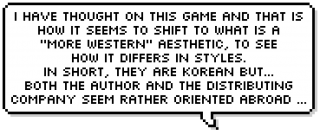

What we will do in Back to the future as soon as we get back to the rubric is compare the text with the paratexts . Actually we already do, we talk about paratexts whenever we talk about packaging , but now you can realize how much the relationship between text and paratext will be extremely important for the generation of storytelling, Pocket Mirror has just met a collision between these two elements, for example, causing a drop in a certain type of audience expectations; they are “road accidents” that can be encountered in the context of the creation of an audiovisual product. It will be one of the many parentheses that we will open on storytelling because the art of narrative in the audiovisual market is closely linked to the production sphere , therefore it will be inevitable to consider the context and the production intentions that have a significant influence on the language adopted by the telling a story.

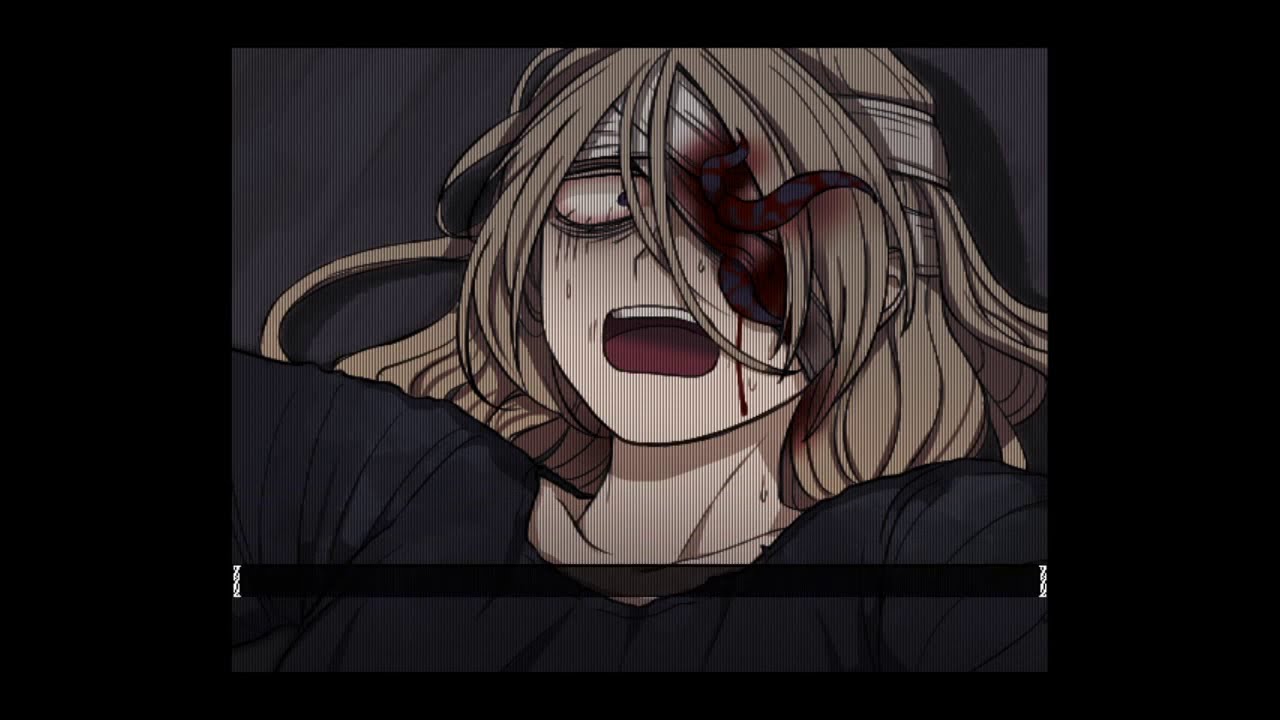

We had a great example in Corpse Party, from the ’96 version made for a contest by an independent author, he just concentrates the information in the finale in order to bring the gaming experience to the fore. While in the version later marketed the priority is to categorize the characters and expand in a more deterministic and clear clues to the plot : let’s take for example the death of Sachiko, the more evident example. In the 1996 version it is summarized in a wall of text , in its commercial alter ego it is shown to be clear and understandable to as many users as possible.

So, after having also concluded our parenthesis, why then are we proposing this article? Why talk about alternative techniques to linear storytelling?

Let’s try to take up a concept mentioned in Mad Father.

Even if the linearity certainly allows to have a wider and potentially interested audience in the story, this does not take away the potential interest of public in more sophisticated style of narration (for example with construction of subtexts) that can be used not only as an alternative style of narration but also as a complementary line to the main plot.

Our long introduction finally concluded …

… We can finally start talking about the three ways adopted by Horror RPGs to propose a story!

Dreaming Mary – The narration IS the gameplay

… What is this music?

Certainly the one of the main title of Dreaming Mary!

In fact, it could only be the best game to start talking about. Do you see how designs and colors are used to immediately create a very strong imagery ?

I’ll start with this bold statement: Dreaming Mary doesn’t have a narrative line, storytelling “doesn’t exist” in this game. The environment and the gameplay phases coincide with the story to such an extent that they become the true form of narration .

Let’s try to remember how it starts.

Here is little Mary. The preface, written in the sky, is really short, the heart of the narrative is all in the gameplay from this point on.

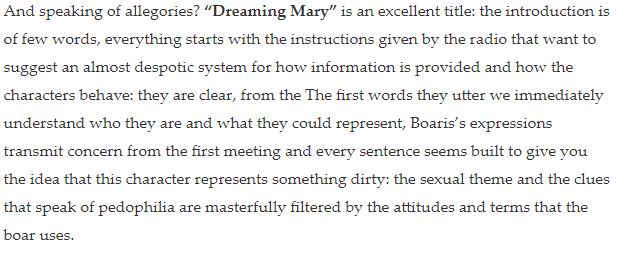

So, we said that storytelling here “does not exist” but it does not mean that there is not a story as for Ao Oni for example wanted to be. The radio speaks as we move and what appears to be instructions for the player already provide elements for the key to the story.

The staging speaks more than any kind of cutscene could , indeed, these are really stripped down and only useful for introducing you to the games of the four characters to face.

Do you see how the characters present themselves? They are extremely communicative with their designs already. Let’s start with the bunny, for example, who will limit herself to welcoming us (or rather, welcome back) and then immediately put us to the test with her minigame and the others will do the same.

There has already been a time when we talked about Dreaming Mary

We were comparing it to a title that did not present a minimum of directing effort in the scenes we were about to see, perhaps we were brazenly comparing two extremes.

Here we said, starting from the environments everything becomes a clue, it is the whole game that performs the communicative function .

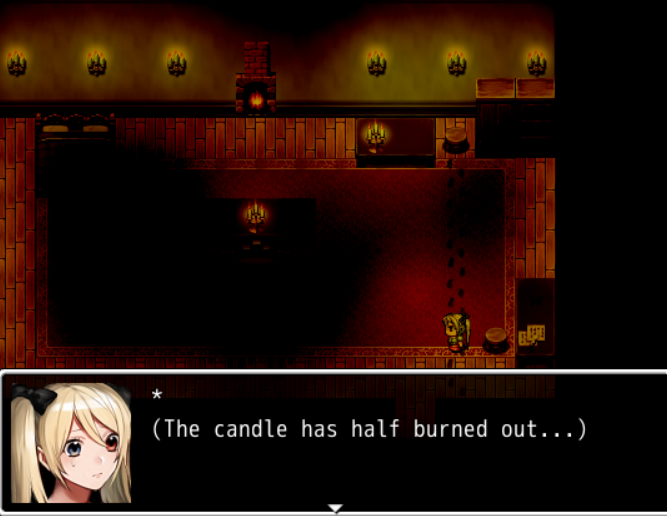

Now the gameplay is divided into three major cycles. Play with Bunnilda, Foxanne, Penn Guindel and then go to Boaris, repeat this flow one more time until the third game gets harder. Then the infringement must be completed and you enter the picture that leads to the world of nightmares, where all the solutions to the games are found and you will have to escape from a threatening shadow.

Then after winning these, collect the seeds and keys (in the nightmare area) that will lead you to the final pursuit that will awaken you in reality where Mari will find the key to be able to get out of the room where she was locked up by her father.

You have noticed, right? There is no cutscene. There is no need to introduce characters, specific contexts, narrative arcs. That’s why I reaffirm convinced that the narration is the gameplay , an even more sophisticated and subtle coordination than the Mad Father gameplay functionality in which there was still a sort of division between cutscenes and gameplay.

We know the father as an antagonistic and abusive figure:

- Through the conversations with Boaris

- By shadow you run away from in a chase

- From the room where Mari wakes up showing us her sad situation.

There are, for example, no cutscenes in which the character is presented to you as happens in Cloé’s Requiem which we will discuss, another title that adopts linear narrative. We do not have the presentation of the character as such as happens in titles such as Angels of Death or Midnight Train, the presence of the father figure is articulated as a threatening aura that takes different forms, from Mari’s dreams to her nightmares and is never even shown to us in reality .

The game is really very explicit in its intentions without ever having to disturb a wall of text and in general without ever resorting to dialogue . The dialogues we have are captured in their essential form, what matters is everything around them, in fact it is difficult to dissect Dreaming Mary into scenes and appreciate only one over the other, the whole game is considered in its essence.

A small masterpiece in the field not only of the Horror RPG video game but I would venture to say in the field of the entire videogame narrative, a type of playful interweaving so brilliant that I have only seen it overcome for a short time by Body Elements .

There are many games that, especially from Generation 0, have tried to communicate only with their “very essence” (music, style, gameplay breakdown) and are among the titles for which I nurture my deepest esteem and admiration: Faust’s Alptraum , Body Elements and then there’s Dreaming Mary. The latter title managed to close perfectly and with great ingenuity a narrative plot that risked never ending or not explaining anything as happened for the other two titles, whose symbolism has taken a turn, overwhelming the importance of “ have something to say ”.

We know that Mary has to act in her dreams and the reason is explained towards the end, the endings of the game do not take deviations from an already decided linear path but deepen the sense of danger of the environment when we see the little girl fall down into her nightmares.

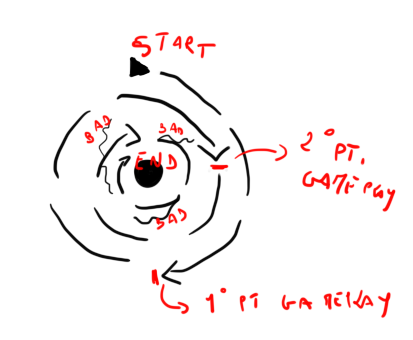

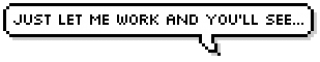

Let’s show a possible narrative scheme of Dreaming Mary and compare it with Mad Father:

Here is the scheme: the narrative continues like a spiral, the dotted lines correspond to the minigames that the characters propose to us three times up to the final part that exposes the protagonist’s objective…

Do you see how different they are? These are all the potentials that can be extracted without necessarily following a standard approach.

I want to conclude this first part with a consideration before moving on to the next title: Dreaming Mary is the only one of these three cases that not only shows an alternative technique to linear narration (“narration is gameplay” , absence of descriptive cutscene or based on linear events) but above all it demonstrates the theme of complementarity . The staging of any audiovisual product can and must act as a complementary feature to the linear narrative thus enriching the meanings of what the main plot shows us .

The genius of this title lies precisely in having based its narrative only on this.

Now let’s finally move on to the next game that-

So yes, Cat in the Box , a game to which we will also dedicate a review. But why talk about it in this space?

Let’s look at it for a moment: it doesn’t even have such a homogeneous aesthetic! The maps compared to those drawn by Dreaming Mary are pure gray stones set with excessive brightness!

We could mention for a moment the lines above on paratexts and packaging in general, it does not seem a title absolutely aimed at a large target and even less at a target of potential spectators as well as players.

Yet Cat in the Box blew me away. Let’s see why together.

Cat in the box – Looking for clues

This game is all that was needed, reaching the state of nirvana where you finally see what Generation 0 can promise in terms of narrative techniques .

There is a resumption of linearity and this phenomenon of “Generation 0 in modern times” we had already mentioned in Purgatory.

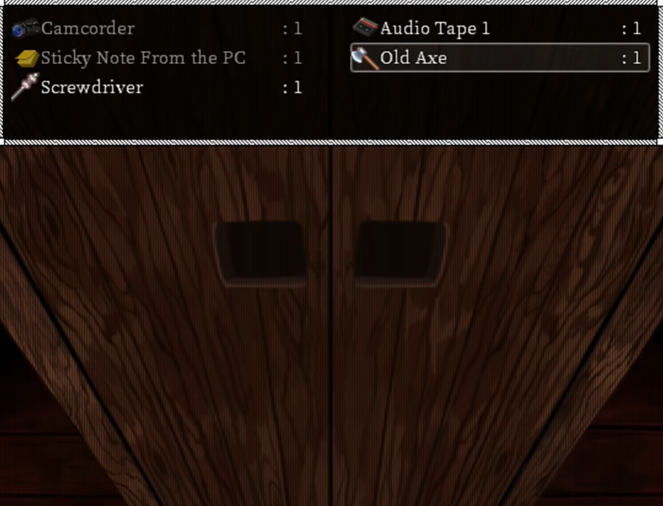

The protagonist to whom we will assign the name wants to leave the abandoned structure in which she sneaked in to impress the web. With an excellent diegetic expedient (speaking to a video camera), we learn that the place where she infiltrated belonged to a Masonic company that was arrested a few days ago.

We also know, in the course of the game experience, that the sect has managed to evoke an ancient divinity that we could define as the cause of all the supernatural facets of the title.

Perhaps following this whole series of information, you would think that a long story with dramatic tones lies ahead, which perhaps like Corpse Party starts from the events of the protagonists to extend attention to the background … But no.

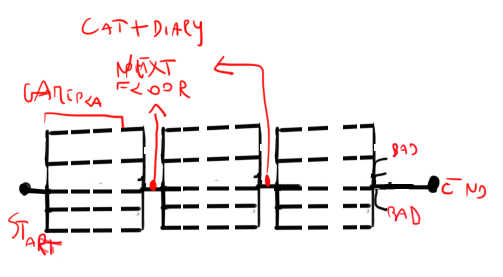

Let’s see together the narrative scheme that the title proposes:

The parallel dotted lines are the actions we perform in the gameplay while the vertical lines indicate some major discoveries.

So here is a rather short straight line from which many parallel lines start that join towards an end point, a term, not towards a conclusive narrative line. The dotted lines as we have done so far represent the actions that we are going to perform with the girl and that join towards a point that would be the end, these follow a linearity that lead to a speech , we want to communicate something specific that materializes in the final image . We can see the difference of this approach with what was with titles like Akemi Tan where there was only linearity in the gameplay with cutscenes to fill the clues, here instead it’s all based about exploration and the elements you find .

We do not have cutscenes in the classic sense of the term even in this second analyzed case. We are presented with the suspense against an unknown presence in the house, but also the scene in which we learn who this presence is is a clue like any other within the plot branch, We never a melodramatic approach that just wants to suggest an intention to tell a story. In this you will understand that is also different from The Witch’s House .

The “cutscene” pauses are certainly shorter than Mad Father’s (well, in the diagram I should have drawn longer lines for Mad Father). The point is that in The Witch’s House, however, there was a background that was then brought to the foreground . In Cat In The Box you don’t have this, there is never a real decisive cutscene in which all the weight and the meaning of the story shifts , the only one there is just a clue as were the other clues of the game….

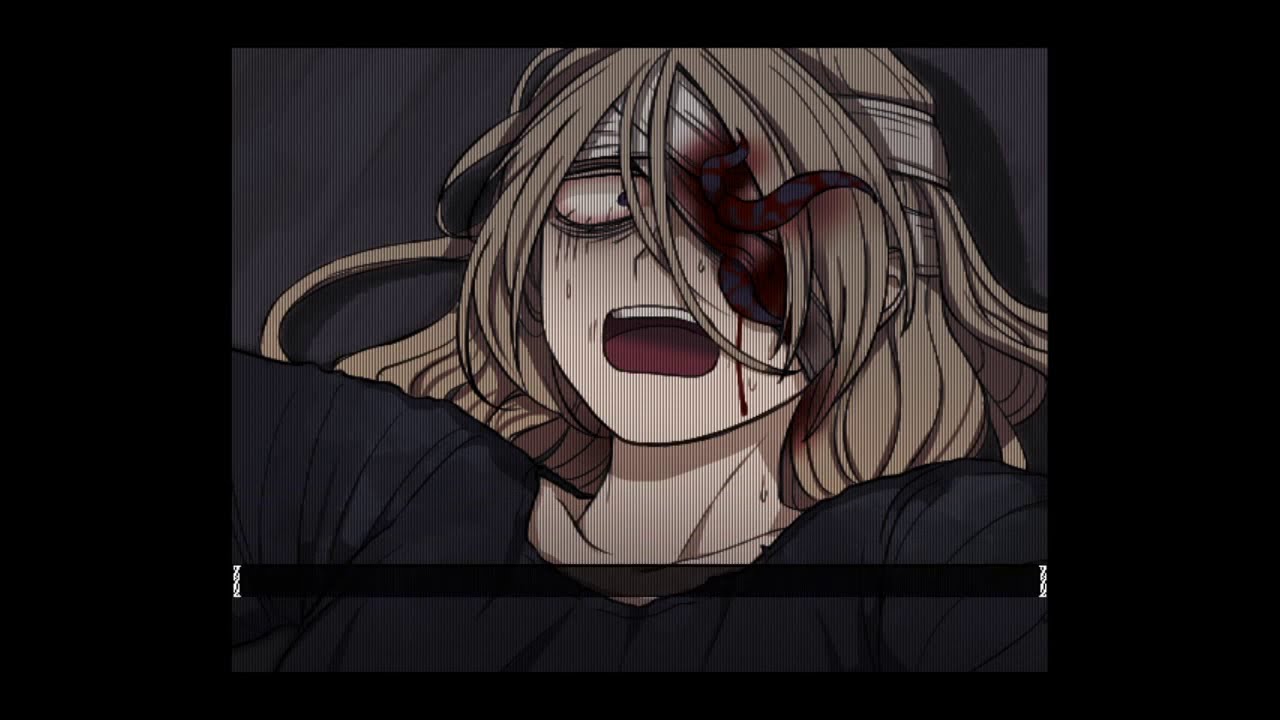

…That combined with the CG shown in the finale perfectly closes the narrative framework (this one comes from the end where our protagonist escaped from the house).

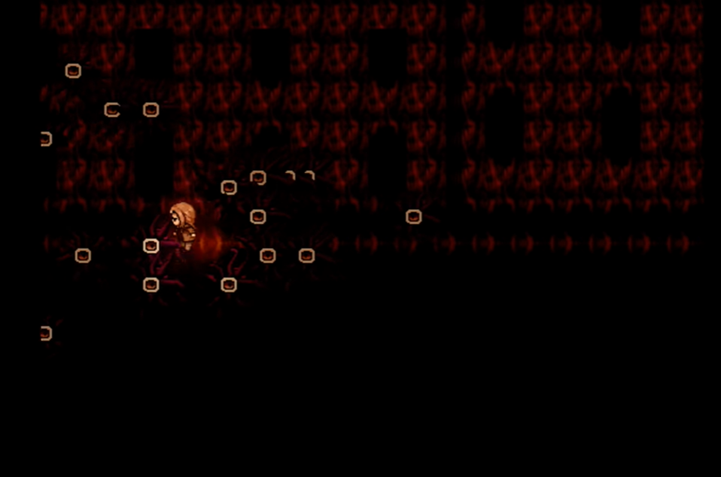

We see the creature appearing during the chases that happen in the nightmares of the girl, that we spoiled on Twitter, for example.

It is not an unexplained phenomenon or left to itself, we could easily interpret it as all the spirits of the girl who in the other timelines have died in the structure and are now trying to possess the body in the present. Such content would have been treated as an extremely dramatic reveal in other narrative titles, not here. They just exist, they only seem to have the function of “monsters chasing you” until the final scene and the image that concludes the title serve as an explanation that allows you to fit all the pieces of the puzzle together.

We could define it as a title that has applied very well and in its own way the lessons we learned from Dreaming Mary: the gameplay phases coincide with the in-depth narrative that the protagonist faces through our control in the exploration phases.

And where is the ingenious move in all of this?

The sobriety . Indeed, the structure. Pure and simple structure that is bared in front of us showing us how it supports the build-game .

The staging does not lend itself much to a communicative function for the title neither with the maps nor with the direction that seems to distance itself from the events and to be very very dry, and that is why the clues you discover assume fundamental importance in the tell the story within the game. Everything happens not “during the exploration phase” but only during the exploration phase , the I consider almost virtuous the way in which the clues have been released and linked together without ever making too much prevail over each other, in fact all the elements of the story are given the same importance until there let’s compare with the answer to the question that the title wanted to launch from the introduction, closing as Dreaming Mary with a message expressed by an excellent circular narrative structure in which the ending matches and responds to prefaces that were made at the beginning.

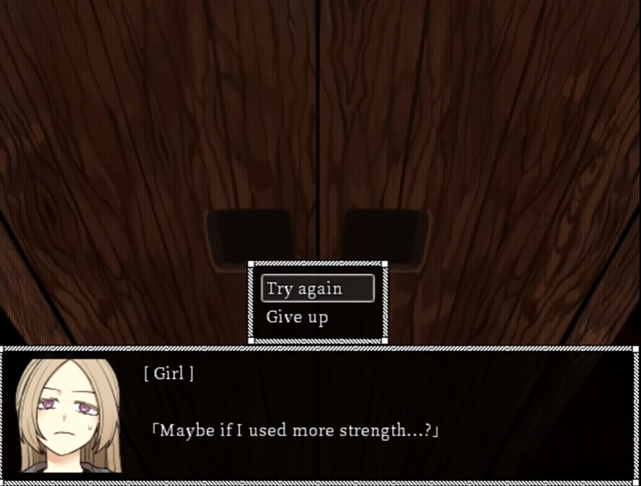

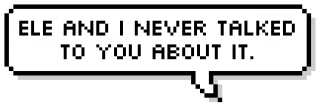

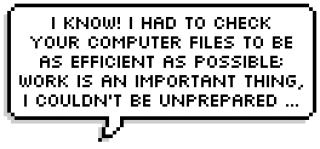

Dear Red – Ramification to the extreme

So, let’s get back to us. Here I promised to speak of three methods alternative to linear fiction. Gentlemen, the one that breaks the mold the most in this sense is definitely Dear Red and takes up the theme of our preface: the endings .

But this title doesn’t do it like the others.

Thus, there are various methods of considering a Horror RPG with multiple endings. These can be a minor alternative to the main line as in Mad Father and numerous other narrative titles, diversifications on the knowledge a player has about a story as in The Witch’s House , events for their own sake as in Hello Hell … or? or The Dark Side Of Red Riding Hood before reaching the finale or, as in Dear Red a way to broaden the knowledge of the background .

I’m certainly not the first person to notice the potential of the method that Sang Gameboy has chosen to tell his story. Here, too, the use of introducing the title with a short sentence that serves as an introduction: otherwise we know very little about the girl when she is in front of the door with the intention of killing her parents’ killer.

A story is not ending, a story is starting.

The actions that can be performed lead us to different scenarios that make us discover a new piece of history. There is no real ending or the right one to go through, if not discovering the one that deepens the plot the most.

The technique has not been deepened enough and that is why the paragraph on this game is likely to be short. But it does not surprise me that the product has had a well deserved success, this is because the method that he has discovered has so much potential and if mixed with others, perhaps combined with a type of linear narrative, it could offer many opportunities to create possible masterpieces.

…………

[1] As any manual says: Events happen in reaction to something.