Tag Archives: cat in the box

Cat In The Box – Recensione

Cat In The Box – Recensione

Buona Vigilia di Natale, e buon lockdown per chi se la passa a casa!

Dato che la protagonista di Cat In The Box, invece, è potuta uscire da casa sua (seppur il gioco sia di quest’anno…) ha deciso, per fare la splendida nel suo canale… Youtube? Dailymotion? Nicovideo? Di esplorare la casa che giorni prima apparteneva ad una setta.

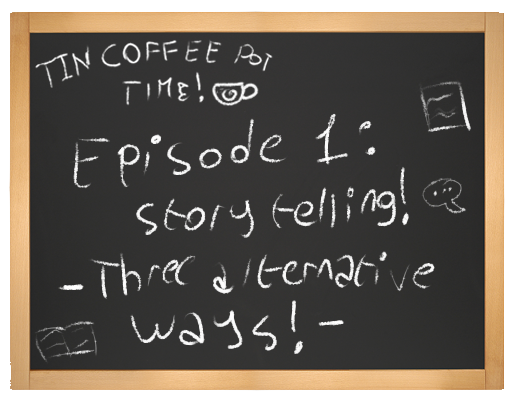

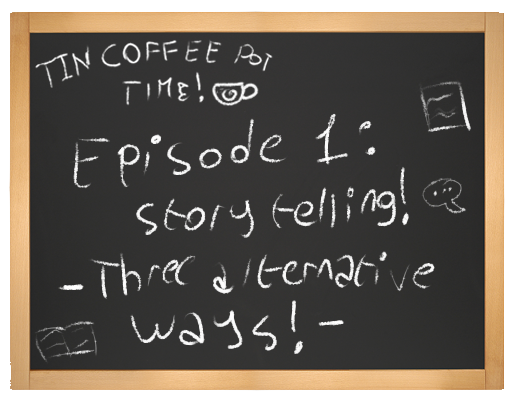

Volete saperne di più sulla trama? PaoGun ha già parlato dello storytelling di questo gioco nel secondo articolo del Tin Coffee Pot Time: “Storytelling – Tre modi alternativi per raccontare una storia”!

Io, Ele, mi occuperò principalmente di parlare delle meccaniche e del gameplay in generale di questo titolo, per cui abbiamo deciso di dedicare questo articolo specifico.

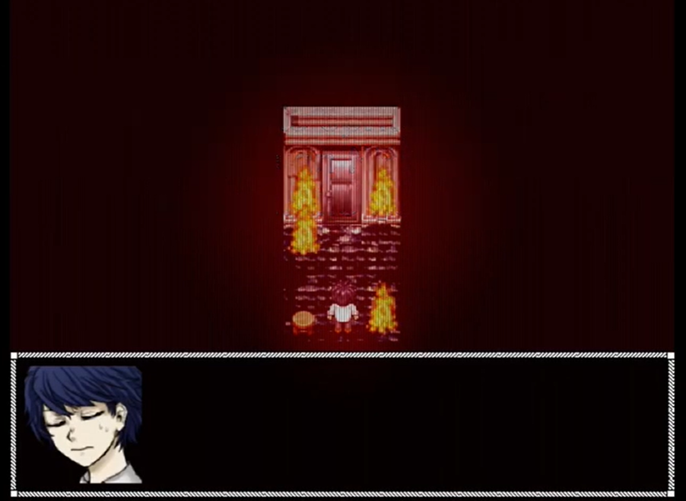

Gameplay – Elementi survival ed inseguimenti divini

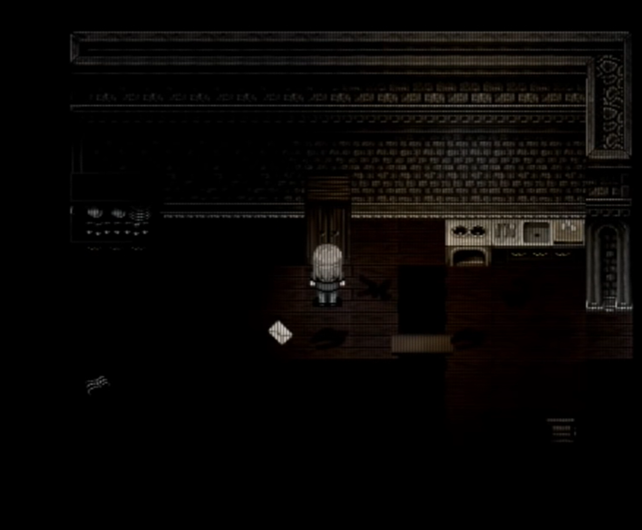

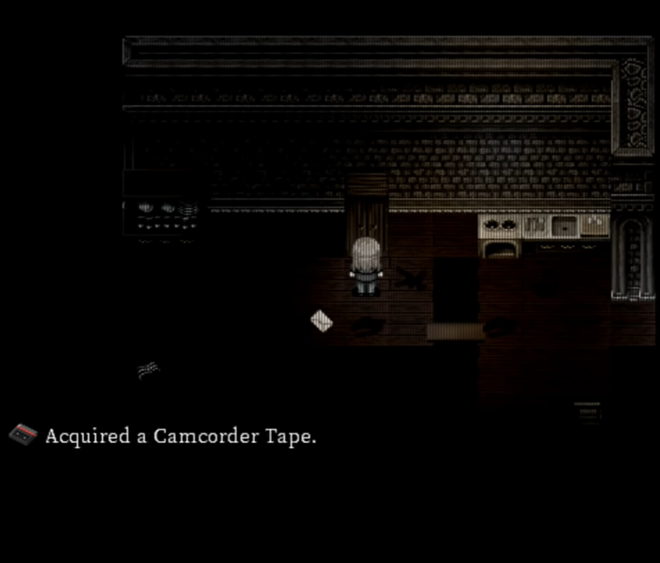

In generale Cat In The Box è davvero piacevole da giocare, le fasi di esplorazione non sono mai noiose e, per fortuna, si trovano costantemente i nastri per la nostra videocamera, così che il giocatore non imprechi solo per salvare la partita e non perdere ore e ore di gioco, così come la cioccolata per non far addormentare il giocatore sulla tastiera per la velocità iniziale della protagonista.

Come avrete già notato dal titolo e da cosa ha detto PaoGun, Cat In The Box è un RPG Horror molto più “occidentale” rispetto a molti che siamo tutti abituati a vedere, seppur la ragazza protagonista sia disegnata in uno stile più o meno anime.

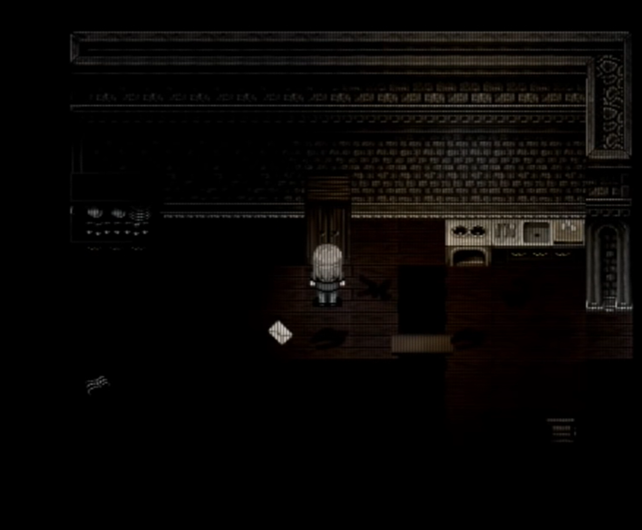

Ma andiamo nel dettaglio, partiamo dalle fasi di esplorazione. Perché ho scritto che è un prodotto che sembra di stampo molto occidentale rispetto ad altri del genere?

Perché, secondo me, il gameplay di Cat In The Box pende sul fronte del survival, tipico sottogenere del gioco horror che si produce tipicamente da noi, rispetto all’RPG Horror tipico giapponese a cui siamo stati tutti abituati.

Il primo elemento che lo rende differente sono gli oggetti limitati per salvare e correre…

Si, ragazzi, so benissimo che Faust Alptraum anche ha la cioccolata per farti correre, stavo spiegando-

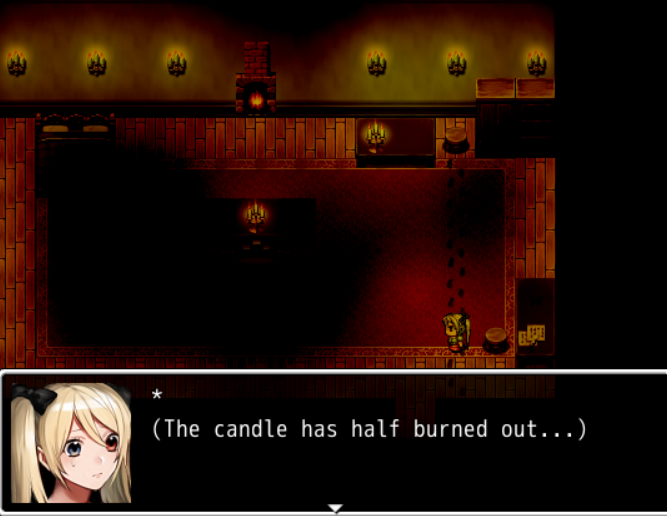

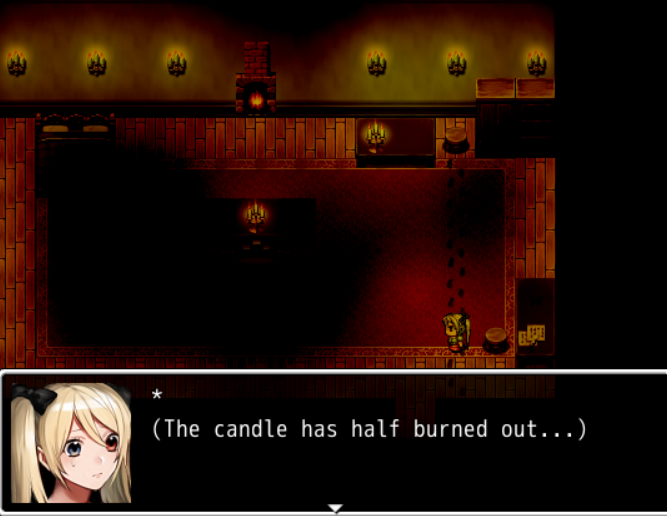

Si, conosco anch’io CaNDLE e il suo sistema della candela ansiogeno!

Mio Dio, fatemi spiegare…

Metteremo proprio a confronto questi due titoli con Cat In The Box.

I primi due, o per via di una cattiva disposizione degli oggetti (in CaNDLE non puoi finire il gioco se non prendi le prime tre candele che si trovano all’inizio) o semplicemente per la meccanica in generale, creano un’ansia costante nel giocatore che dovrà costantemente controllare il livello della candela di Ca o l’energia di Elisabeth.

Ora, non parlerò del come poteva essere fatto meglio questo sistema nel dettaglio, ma dico solo che in entrambi i giochi quest’ansia dell’avere un game over vero e proprio da un momento all’altro per via degli oggetti limitati… Rende entrambi i titoli semplicemente più ansiosi e con giocatori più propensi al ragequit, se mi permetto di esagerare. Questo è perché mettono la situazione sempre “sul filo di un rasoio”, soprattutto CaNDLE (vorrei precisare che Faust Alptraum soffre molto meno di questo problema rispetto a CaNDLE, avendo un posizionamento degli oggetti indispensabili discreto).

Quindi Cat In The Box cosa ha fatto?

Si è semplicemente reso maestro di questo sistema, dando come oggetti limitati la velocità e la possibilità di salvataggio. È stata una scelta intelligente, onestamente, perché non ci si ritrova nel ritmo perenne in cui rischi di avere un game over in ogni secondo e bisogna controllare costantemente dei livelli di qualcosa, senza goderti nulla del titolo, che ha anche delle belle atmosfere.

Ma l’effetto di ansia è papabile lo stesso, dato che viene limitata una cosa vitale come il salvataggio. Quindi il giocatore non si ritrova oppresso dalla meccanica, ma si ritrova una vera e propria sfida… Come dovrebbe essere.

Se non ci si gestisce bene l’uso dei nastri, sei costretto a continuare a giocare finchè non ne trovi un altro (il che non è mai troppo tardi, avendo il gioco una buona disposizione degli oggetti). L’esperienza non viene dagli avvertimenti che successivamente ti danno un game over di botto, bensì dalle conseguenze se non gestisci bene la situazione in cui sei.

E questo, per me, lo rende più “survival” degli altri due titoli che ho citato. Il survival si basa perennemente sul gestire la propria situazione attuale, avendo conseguenze certo scomode, ma che non ti fanno finire la partita istantaneamente…

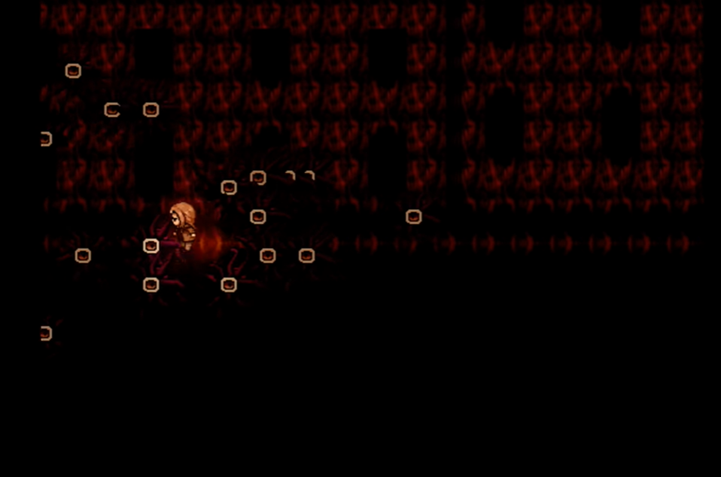

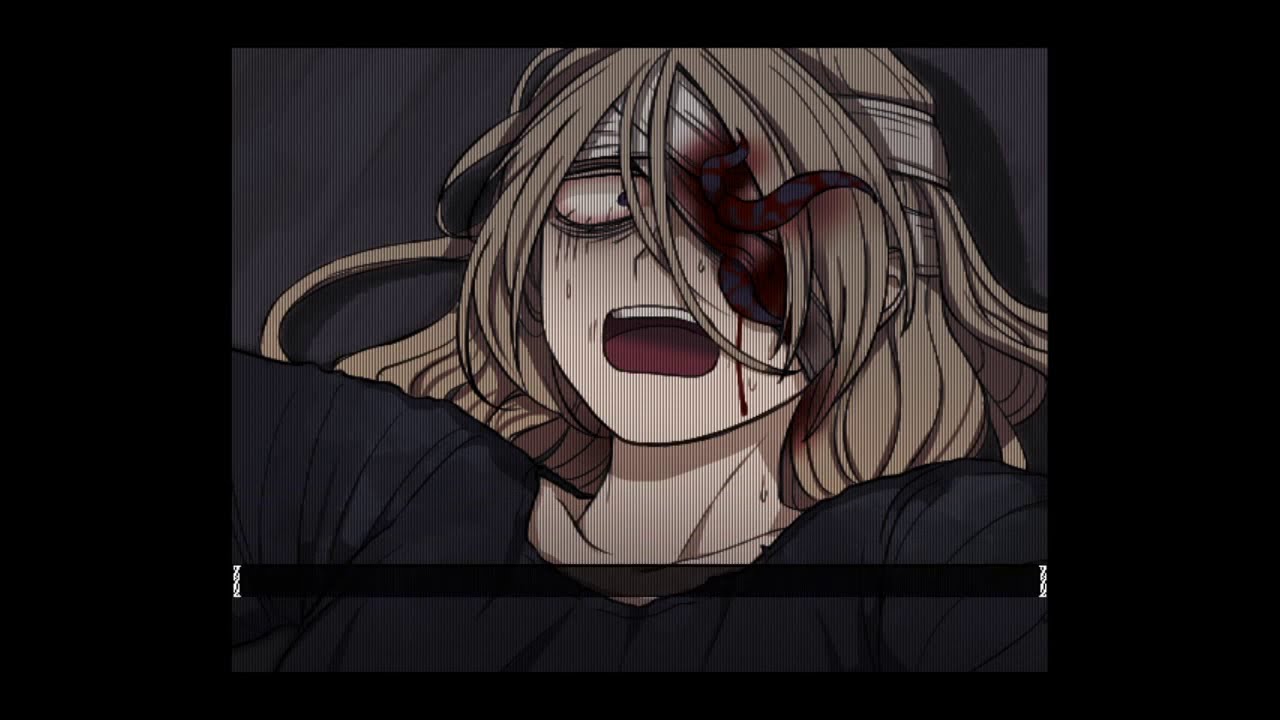

Come può fare un inseguimento contro, probabilmente, una versione di te stessa da un’altra linea temporale.

Ecco, siamo arrivati al secondo punto di questo paragrafo della recensione.

Come diceva il titolo, ho adorato gli inseguimenti in questo gioco.

A livello più tecnico, il fatto che il gioco ci da una stamina limitata aggiunge molto, dato che non potremo sempre andare sempre e comunque full-speed, quindi se non abbiamo rimedi per la stamina (molto rari, io ne avrò trovato uno durante la mia giocata) dobbiamo imparare a dosare bene la velocità… Ma dato che gli inseguimenti (permettetemi l’assolutismo, seriamente. Ho giocato così tanti giochi inutilmente difficili che queste cose mi rendono esageratamente felice.) sono stati fatti bene, questa cosa non rende il gioco più incline a far salire l’isteria a persone come me, ma semplicemente aggiunge sfida!

Ma oltre a una bellissima giocabilità, la cosa che ho apprezzato di più è, esco dal mio campo, il concept di molti degli inseguimenti, in generale.

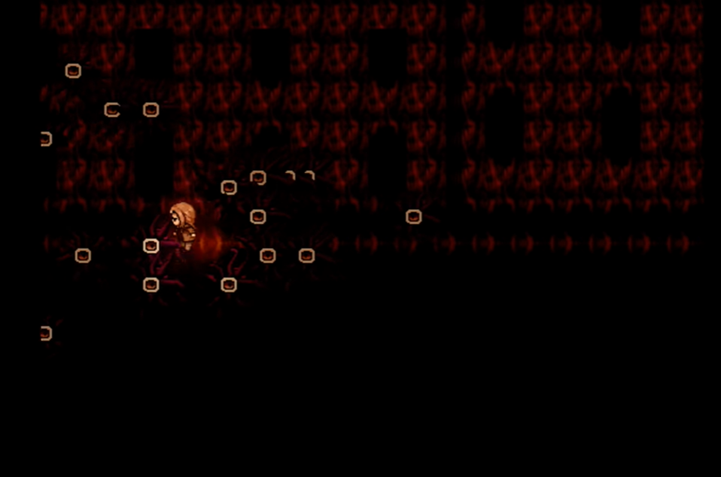

Molti sono stati aiutati, a livello di idee, dal fatto che l’antica divinità evocata dalla setta citata nel gioco è la causa di tutto questo loop temporale…

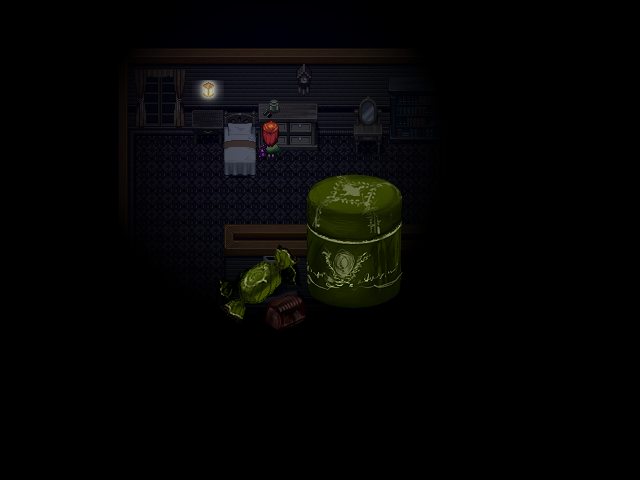

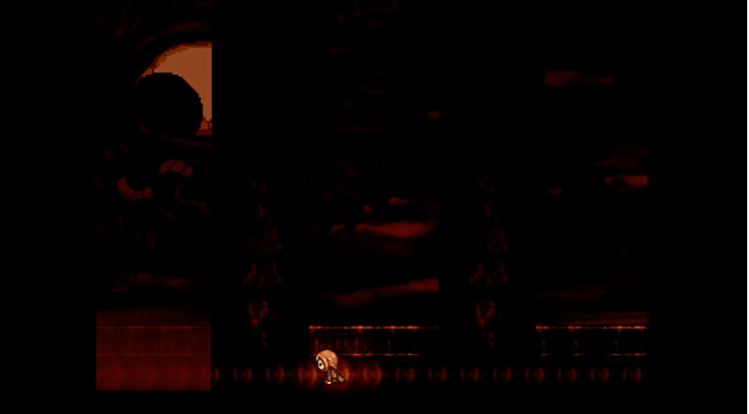

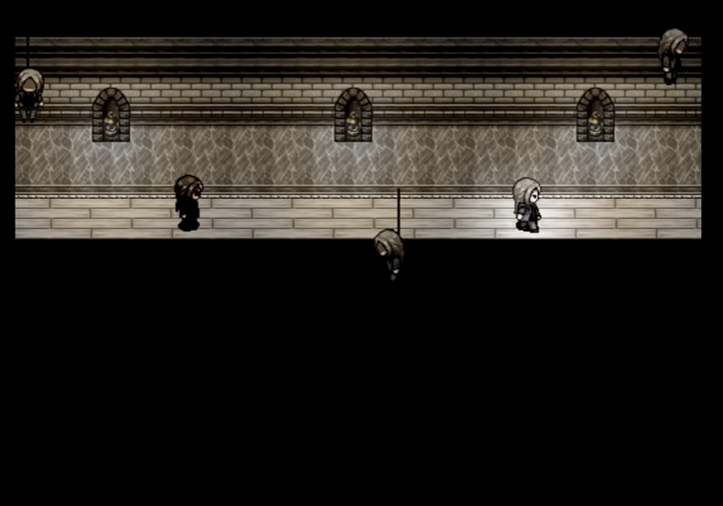

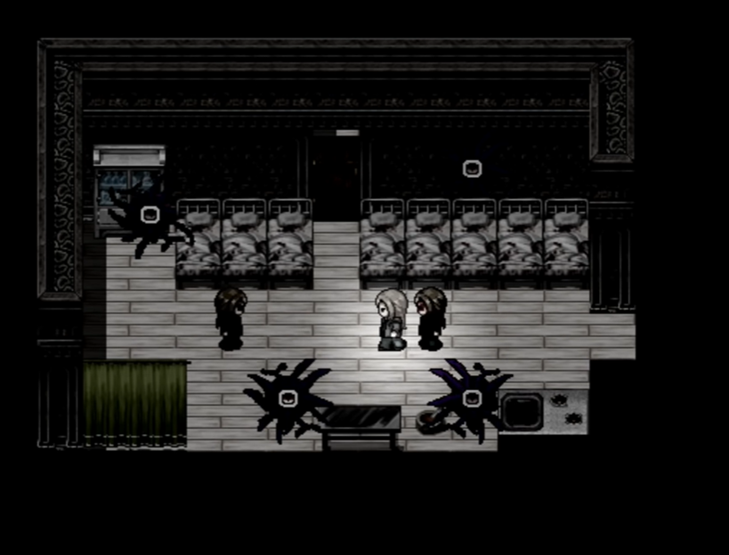

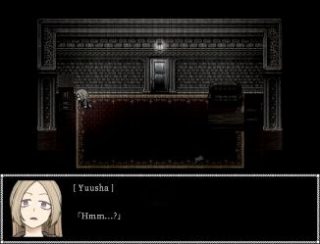

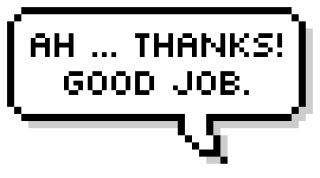

(Quella sopra è più una fase stealth che ho ugualmente apprezzato molto)

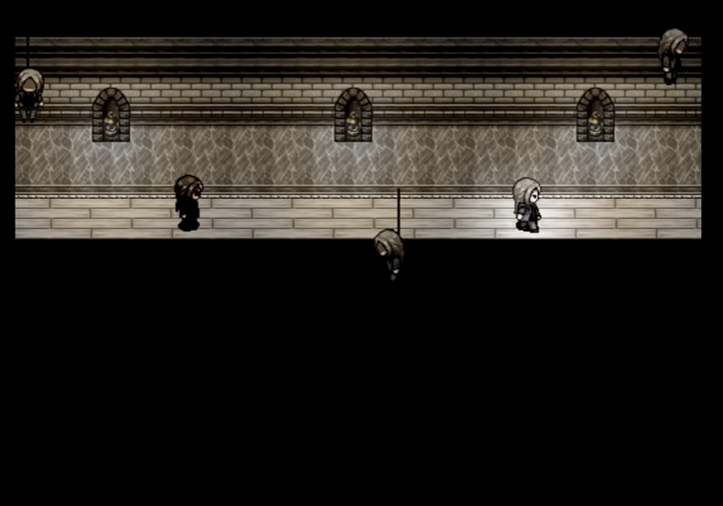

Ma soprattutto quelli che hanno a che fare in qualche modo con le copie della protagonista…

…Sono diventati un elemento vincente, dato l’espediente quasi “meta” delle linee temporali.

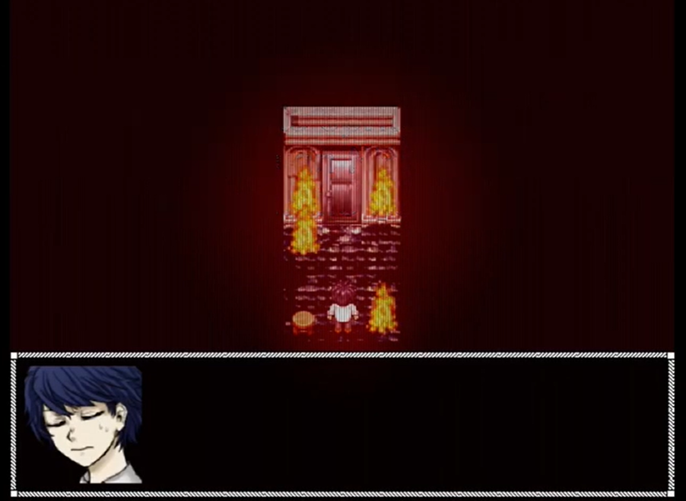

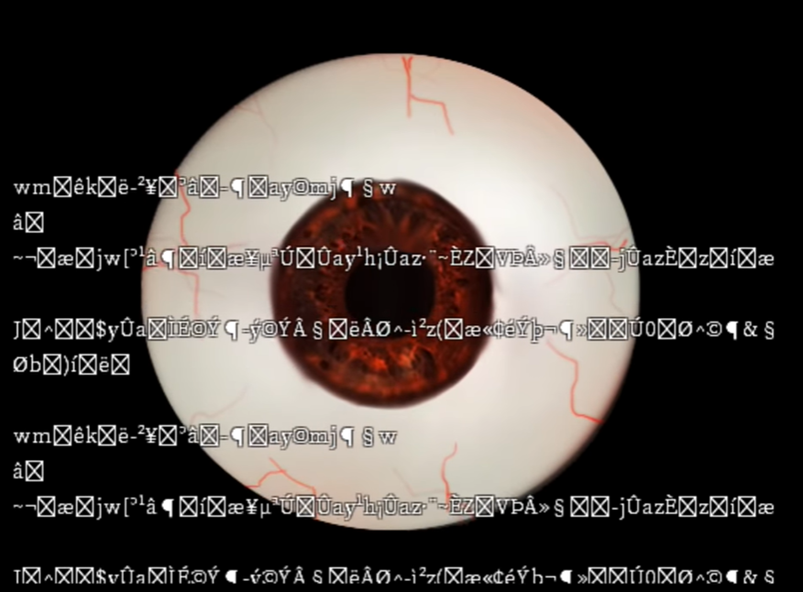

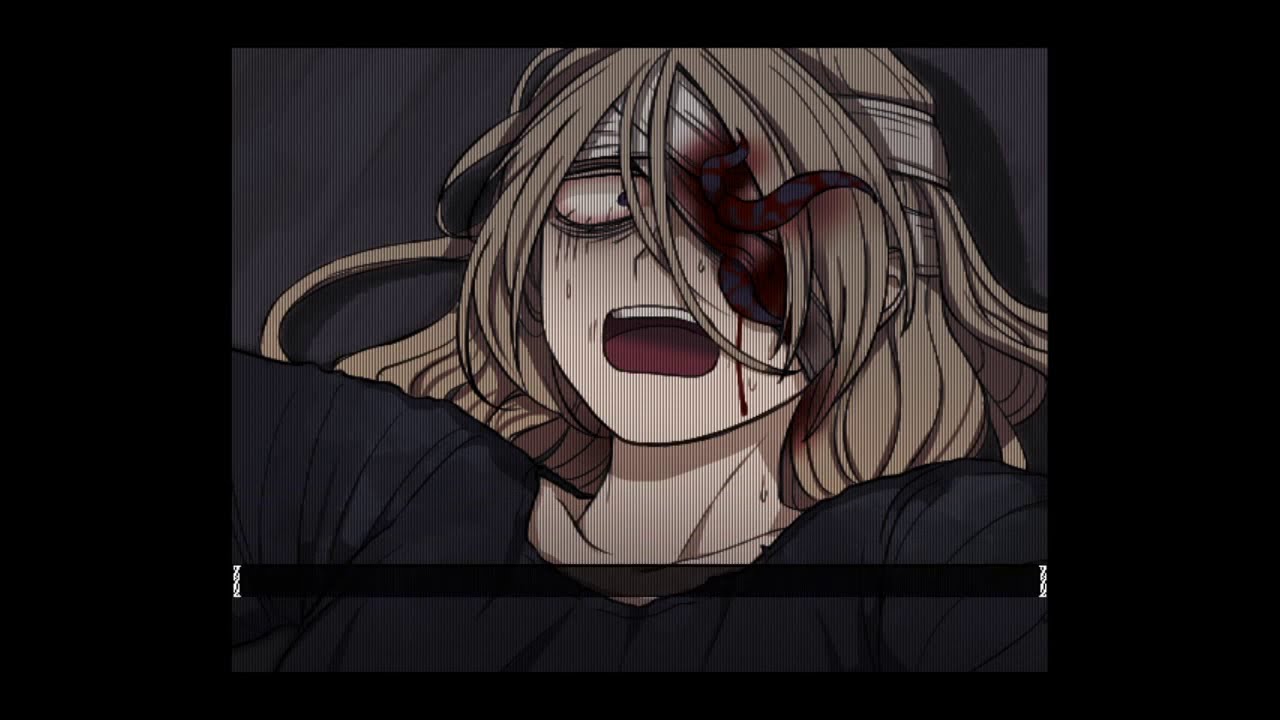

Ma oltre alle belle, inquietanti, mai troppo invasive, mai troppo banali… E che fanno anche foreshadowing sul plot twist principale, visuali in cui facciamo correre la protagonista, molti altri elementi di Cat In The Box si basano sul tema delle anomalie temporali.

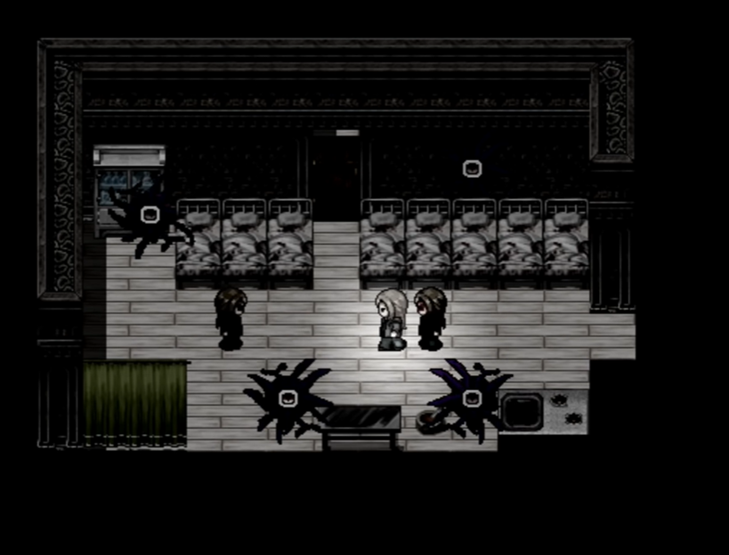

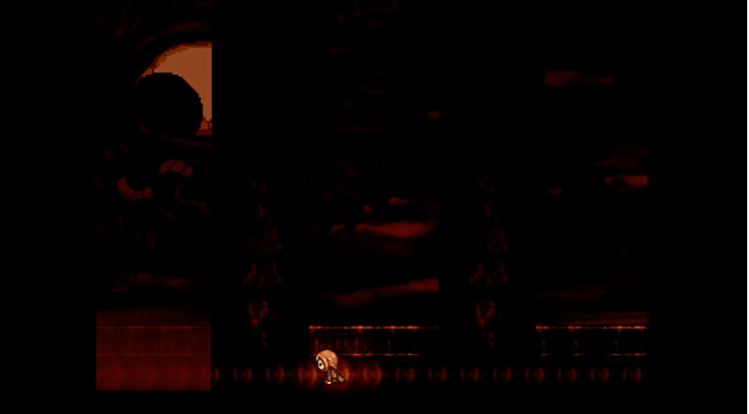

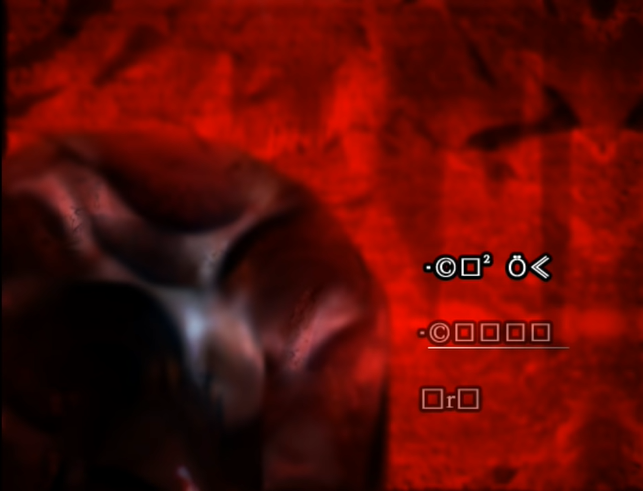

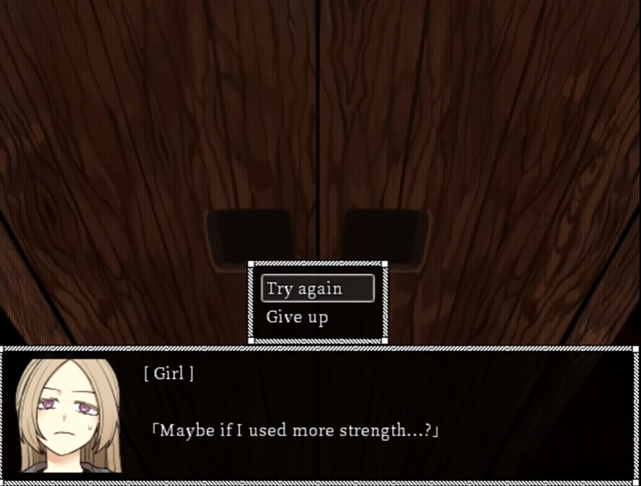

Infatti, tornando per qualche secondo sugli inseguimenti, quando si viene catturati succede sempre qualcosa di strano al livello del gioco vero e proprio.

Ecco un esempio.

(In realtà questo cambiamento della schermata del titolo avviene anche se si va semplicemente al menu principale tramite il menu di gioco, se si è “fortunati”, ma almeno a me è successo quando sono stata catturata dalla copia della protagonista)

E se si clicca la prima voce… Il gioco non è che si chiude solo, o qualcosa di più semplice… Bensì crasha dopo questa schermata con testo scorrevole.

“Un crash obbligato, che figata è?! Cioè non è solo uno ‘SceneManager.exit’*, crasha proprio!!”

–Io appena ho avuto questo game over, visibilmente emozionata.

*chiamata script usata su RPG Maker VX Ace per chiudere direttamente il gioco

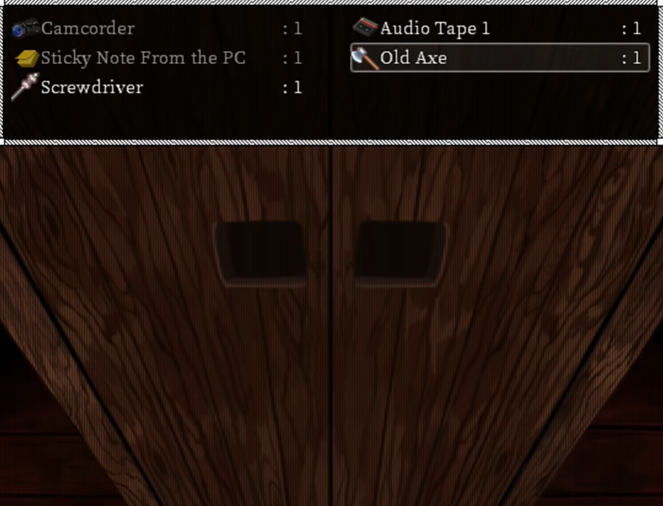

Da qui apriamo il capitolo che finisce questo spezzone molto entusiasta della recensione: gli easter egg e i segreti.

Questi sono… Semplicemente tantissimi! Davvero, c’è persino un video di un intero minigioco inutilizzato che collega Cat In The Box a Stygian, il gioco precedente a questo, sempre della PsychoFlux Entertainment!

Ma in quest’articolo ve ne lascio un assaggio.

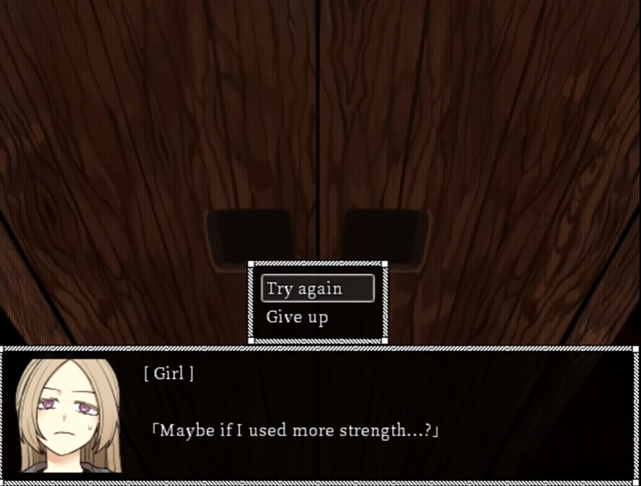

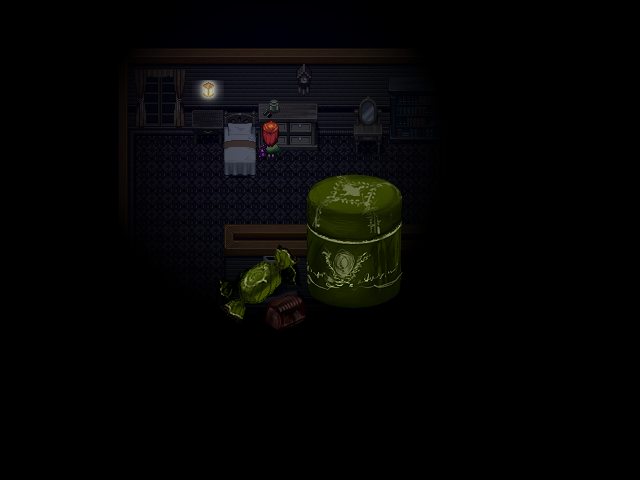

Se controllate quest’armadio quando il primo killer è morto…

E dopo aver provato ad usare più forza, senza successo…

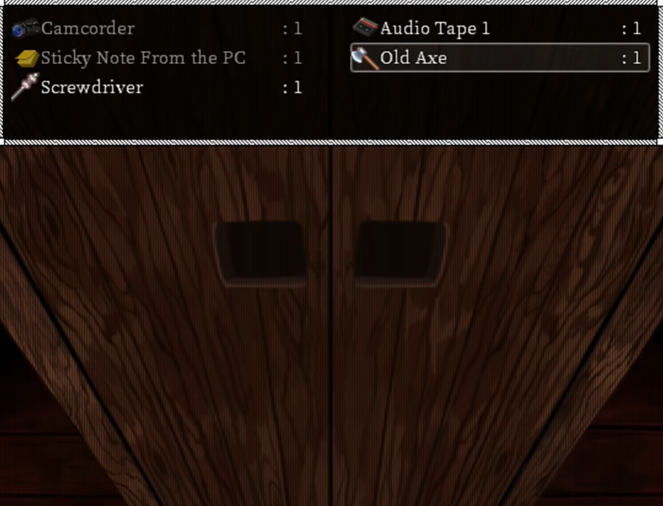

…Ottenete l’ascia e poi, prima di andare al piano di sopra tornate a questo armadio…

…Hmm, già, perchè ha un nastro per la videocamera e ha i nostri stessi vestiti?

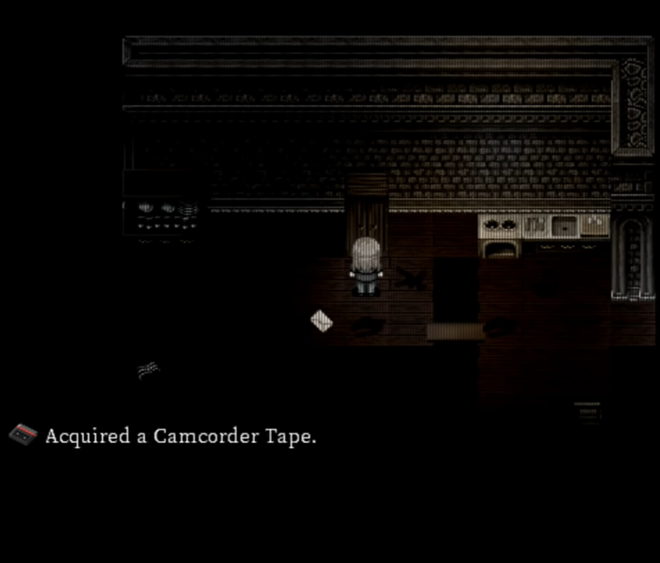

Oh, otterrete un nastro per la videocamera! Che fortuna!

…Ah, questo gioco è bellissimo, non ho davvero dubbi su questo.

Dopo le nostre prime due recensioni cariche d’odio e amarezza (spoiler: ci sarà più odio successivamente, just you wait) e il nostro apprezzamento per Purgatory, abbiamo trovato in un gioco di quest’anno davvero un’altra perla.

Con un inizio da tipico film slasher, con un plot twist che ha attorno degli elementi di foreshadowing a tratti anche incredibili, assieme ad un gameplay ben pensato, equilibrato e mai lasciato all’approssimazione perché “tanto è un RPG Horror” ed un aesthetic quasi occidentale, per noi Cat In The Box rimarrà per lungo tempo un importante punto di riferimento e confronto.

Cat In The Box – Review

Cat In The Box – Review

Happy Christmas Eve, and happy lockdown for who’s home!

Since the protagonist of Cat In The Box, instead, was able to leave her house (even if the game was released this year…) she decided, to be popular on her… Youtube? Dailymotion? Nicovideo channel? To explore the house that days before belonged to a cult.

Want to know more about the plot? PaoGun has already talked about the storytelling of this game in the second article of Tin Coffee Pot Time: “Storytelling – Three alternative ways to tell a story”!

I, Ele, will mainly take care of speaking of the game mechanics and gameplay in general of this title, for which we decided to dedicate this specific article.

Gameplay – Elements of survival and divine chases

In general Cat In The Box is really enjoyable to play , the exploration phases are never boring and, luckily, we constantly find the tapes for our camera, so that the player does not rage-quit just to save the game and doesn’t waste precious game hours, as well as chocolate to keep the player from falling asleep on the keyboard due to the initial speed of the protagonist.

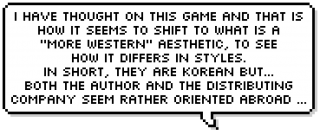

As you may have already noticed from the title and what PaoGun said, Cat In The Box is a much more “Western” Horror RPG than many that we are all used to seeing, although the girl protagonist is drawn in a more or less anime style.

But let’s go into detail, let’s start from the exploration. Why did I write that it is a product that looks very Western compared to others of its kind?

Because, in my opinion, the Cat In The Box gameplay hangs on the survival front , a typical sub-genre of the horror game that is typically produced by us in the West, compared to the typical Japanese Horror RPG we have all been used to.

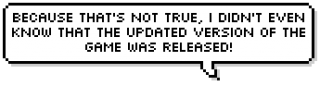

The first element that makes it different are the limited objects to save and run…

Yes, guys, I know very well that Faust Alptraum has chocolate to make you run, I was explaining-

Yes, I also know CaNDLE and its anxiety-inducing candle system!

My God, let me explain…

We will compare these two titles with Cat In The Box.

The first two, or due to a bad arrangement of objects (in CaNDLE you cannot finish the game if you don’t take the first three candles that are at the beginning) or simply for the mechanic in general, create a constant anxiety in the player who will have to constantly check the level of Ca’s candle or Elisabeth’s energy.

Now, I won’t talk about how this system could have been better in detail, but I just say that in both games the anxiety of having a real game over at any moment due to the limited objects… Makes both titles simply more anxiety-inducing and with players more inclined to ragequit, if I allow myself to exaggerate. This is because they always put the situation “on a razor’s edge” , especially CaNDLE (I would like to point out that Faust Alptraum suffers much less from this problem than CaNDLE, having a discrete positioning of the indispensable objects).

Then what did Cat In The Box do?

It has simply mastered this system, giving as limited objects the speed and the possibility of saving . It was a smart choice, honestly, because you don’t find yourself in the perennial rhythm in which you risk having a game over every second and you have to constantly check the levels of something, without enjoying anything of the title, which also has a nice atmosphere.

But the effect of anxiety is still eligible , since something as vital as saving is limited. So the player isn’t overwhelmed by the mechanics, but finds a real challenge… As it should be.

If you do not use tapes well, you are forced to continue playing until you find another one of them (which is never too late, since the game has a good arrangement of objects). The experience does not come from the warnings that subsequently give you a game over suddenly, but from the consequences if you do not manage in the right way the situation you are in.

And this, for me, it makes this game more “survival” than the other two titles I mentioned . Survival is perpetually based on managing your current situation, having inconvenient consequences, but don’t give you a game over instantly…

…Like a chase against probably a version of yourself from another timeline can do.

Here, we have come to the second point of this paragraph of the review.

As the title said, I loved the chases in this game.

On a more technical level, the fact that the game gives us a limitated stamina adds a lot, as we won’t always be able to go full-speed, so if we don’t have any remedies for stamina (very rare, I have found only one of them during my play) we must learn to dose speed well… But since the chases (allow me absolutism, seriously. I’ve played so many unnecessarily difficult games that these things make me exaggeratedly happy.) have been done right, this element doesn’t make the game more inclined to give hysteria to people like me, but just adds challenge!

But besides a beautiful gameplay , the thing I liked the most is, I get out of my field, the concept of many of the chases, in general.

Many of tham have been helped, in terms of ideas , by the fact that the ancient deity evoked by the cult mentioned in the game is the cause of all this time loop…

(The one above is more of a stealth phase which I also really appreciated)

But especially those who have to do in somehow with the copies of the protagonist…

…Have become a winning element , given the almost “meta” expedient of the timelines.

But besides beautiful, disturbing, never too invasive, never too trivial … And also foreshadowing the main plot twist, visuals in which we make the protagonist run, many other elements of Cat In The Box are based on the theme of temporal anomalies.

Indeed, returning for a few seconds on the chases, when you get caught something weird always happens at the actual game level.

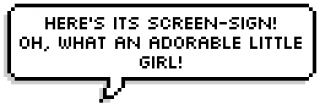

Here’s an example.

(Actually this screen change of the title happens even if you simply go to the main menu via the game menu, if you are “lucky”, but at least it happened to me when I was captured by the copy of the protagonist)

And if you click the first choice… The game doesn’t just close, or something simpler… It crashes after this scrolling text screen.

“An obliged crash, how cool is that?! That is, it’s not just a ‘SceneManager.exit’ * , it just crashes!!”

– I just got this game over, visibly excited.

* script call used on RPG Maker VX Ace to force-close the game

From here we open the chapter that ends this very excited paragraph in this review: the easter eggs and secrets.

These are… Simply a lot! Really, there’s even a video of an entire unused minigame connecting Cat In The Box to Stygian, a game precedent to this, also from PsychoFlux Entertainment!

But in this article I leave you a tasting.

If you check this cabinet when the first killer is dead …

And after trying to use more force, without success …

…You get the ax and then, before you go upstairs go back to this closet…

…Hmm, yeah, why it has a camrecorder and has the same clothes as us?

Oh, you will get a tape for the camera! Lucky you!

…Ah, this game is beautiful, I really don’t have doubts about this.

After our first two reviews full of hatred and bitterness (spoiler: there will be more hate later, just you wait ) and our appreciation for Purgatory, we found another gem in this year’s game.

With a typical slasher film start, with a plot twist that has around some elements of foreshadowing, at times even incredible, together with a well thought out and balanced gameplay, also never left to approximation because “eh, it’s Horror RPG anyway” and an almost western aesthetic, for us Cat In The Box will remain for a long time an important point of reference and comparison.

RPG Horror and Storytelling – Three Alternative Ways to Tell a Story!

And precisely because it is coming, that activity that we would all dream of doing at least once in our life returns: listening to stories in front of the fireplace, especially when they have to do with the world of mystery!

So, you will have understood what I am talking about, of course, about storytelling in the context of Horror RPGs! Well, after all, it was also the title of the article. Yup.

What to say, we started this year’s season with a lot of premises and discussions but finally we will be able to begin to resume together the slightly more theoretical approaches, in the article on Purgatory I had badly run away … I was looking forward to this one!

What are the premises for this article?

To begin with, the advice I propose is that I am not a scholar of some kind of videogame storytelling class. Everything I will say here is based only on the observation I had the opportunity to make during my experience with Horror RPGs.

What I noticed in general, even though I’m ignorant on the subject, was that in the world of video games the narration has never been an element for which the media has distinguished itself and the complexity of a plot is also scarcely considered in a proper manner, not to mention the issue of multiple endings. It is not only in the context of RPG Horror or in Japanese titles such as the various visual novels and route models, many Western titles also seem to take advantage of this method. I could mention titles like Detroit: Become Human which are based on numerous endings depending on the game choices. Many have considered it as an admirable operation and to be commended, I can understand why, but. There is a but.

It seems to me a “too comfortable” move. What I ask myself is how much it is worth staggering the responsibility of entrusting the player with the progress of a story, I would see it as an excuse to never make a final decision. Leaving aside the cases where the story is linear and technically only an ending is right, I take advantage of this premise to state that the theme of the endings is the last thing we will worry about in this article .

I know it had to be said, because it is now one of the key features for which RPG Horror is known, indeed, one of the few formalities in the narrative field for which the genre is recognized.

By making a short historical re-cap we try to remember one of the key elements of this genre: the clues inherent to the storyline are discovered during the exploratory phase which often distances itself from the part of a story in which there are cutscenes. Good.

Then we will remember that Mad Father introduced and made the public recognize the basics of linear narration in which the discovery of the clues of a story are strictly limited to a precise context. Let us remember, perfectly introduced the theme of linear narration in an area as wide as the videogame one in which everything is in the hands of the player.

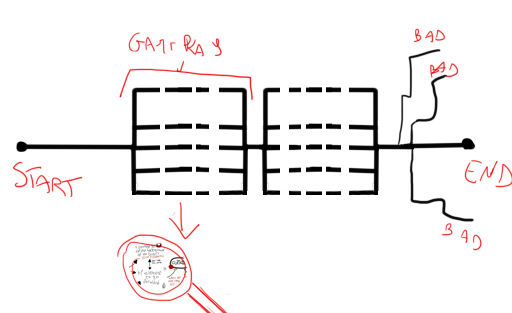

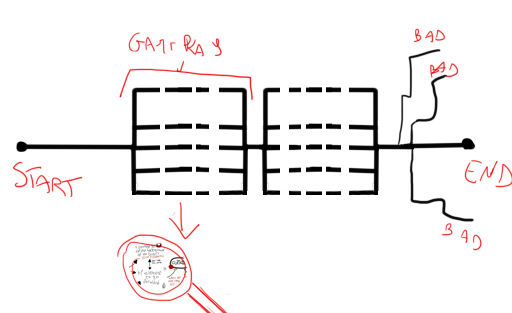

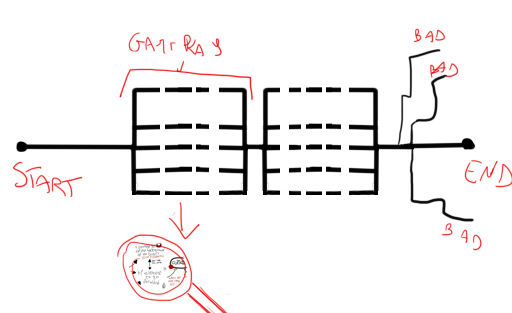

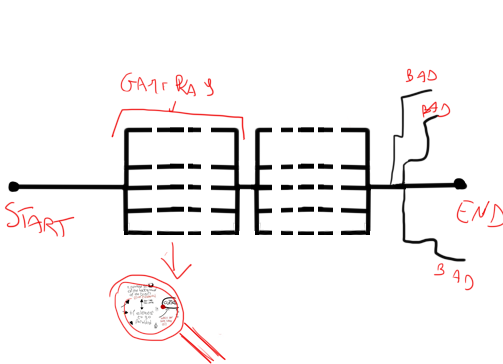

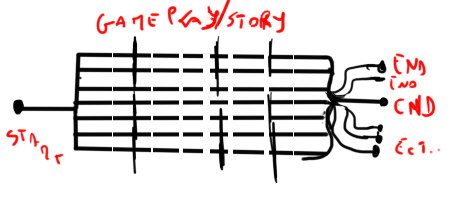

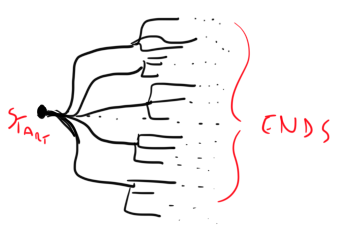

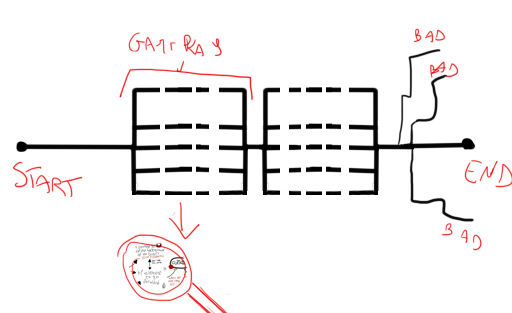

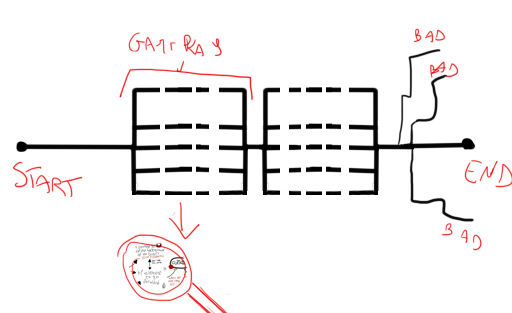

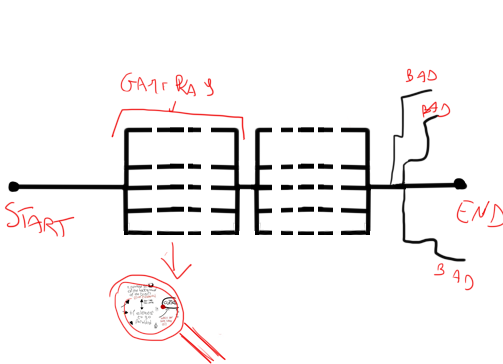

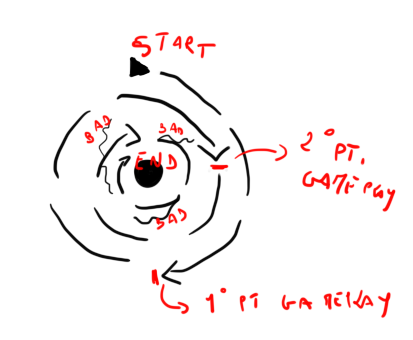

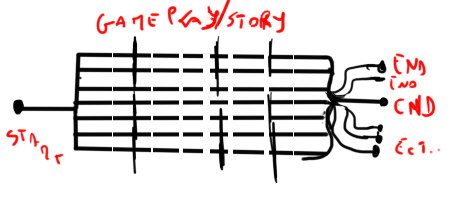

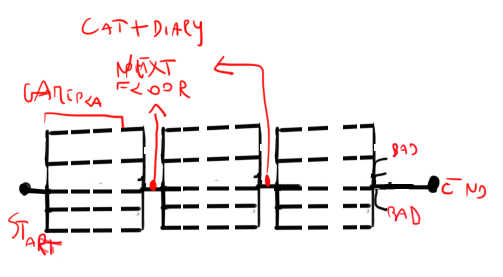

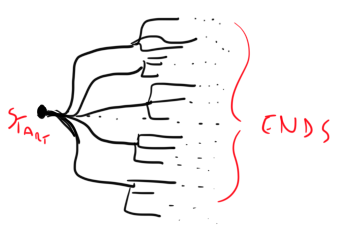

Let’s review this concept for a moment, I leave you this outline here.

… Ahem.

Here, good young lady, calmly go back to work.

So, yes, our assistant has speeded things up a bit too much, we’ll deal with the three screens later …

Rather let’s see the scheme he proposes before concluding the speech on Mad Father.

We have the unique narrative line, the parallel dotted lines you see are all those clues and flashbacks that are scattered throughout the game, but then as you can see they all come back to a single narrative line that never stops being only one and stable and based on the cause-effect relationship [1] , a feature that is already distinguished by the fact that the gameplay phase the level of action and understanding of the story is, however, different from the “big scenes” that carry on the plot. And this goes on until the final act, to be exact the reaching of the breakpoint in which the endings branch out only in the context of the conclusive climax, these lines as you can see go well with the scheme on the free gameplay that Ele had done in the article dedicated to Mad Father.

……So….Here’s my scheme again.

As you can see I marked the endings with thinner lines to indicate the little impact on the main narrative line, the game makes you understand very well the chosen path. The various “bad ends” are different consequences to types of events, do not distort the personality of the characters.

At this point you must have understood one thing: the narration I am referring to refers only to the text . The text is the game itself and is read, understood and interpreted just as one reads a sentence.

What we will do in Back to the future as soon as we get back to the rubric is compare the text with the paratexts . Actually we already do, we talk about paratexts whenever we talk about packaging , but now you can realize how much the relationship between text and paratext will be extremely important for the generation of storytelling, Pocket Mirror has just met a collision between these two elements, for example, causing a drop in a certain type of audience expectations; they are “road accidents” that can be encountered in the context of the creation of an audiovisual product. It will be one of the many parentheses that we will open on storytelling because the art of narrative in the audiovisual market is closely linked to the production sphere , therefore it will be inevitable to consider the context and the production intentions that have a significant influence on the language adopted by the telling a story.

We had a great example in Corpse Party, from the ’96 version made for a contest by an independent author, he just concentrates the information in the finale in order to bring the gaming experience to the fore. While in the version later marketed the priority is to categorize the characters and expand in a more deterministic and clear clues to the plot : let’s take for example the death of Sachiko, the more evident example. In the 1996 version it is summarized in a wall of text , in its commercial alter ego it is shown to be clear and understandable to as many users as possible.

So, after having also concluded our parenthesis, why then are we proposing this article? Why talk about alternative techniques to linear storytelling?

Let’s try to take up a concept mentioned in Mad Father.

Even if the linearity certainly allows to have a wider and potentially interested audience in the story, this does not take away the potential interest of public in more sophisticated style of narration (for example with construction of subtexts) that can be used not only as an alternative style of narration but also as a complementary line to the main plot.

Our long introduction finally concluded …

… We can finally start talking about the three ways adopted by Horror RPGs to propose a story!

Dreaming Mary – The narration IS the gameplay

… What is this music?

Certainly the one of the main title of Dreaming Mary!

In fact, it could only be the best game to start talking about. Do you see how designs and colors are used to immediately create a very strong imagery ?

I’ll start with this bold statement: Dreaming Mary doesn’t have a narrative line, storytelling “doesn’t exist” in this game. The environment and the gameplay phases coincide with the story to such an extent that they become the true form of narration .

Let’s try to remember how it starts.

Here is little Mary. The preface, written in the sky, is really short, the heart of the narrative is all in the gameplay from this point on.

So, we said that storytelling here “does not exist” but it does not mean that there is not a story as for Ao Oni for example wanted to be. The radio speaks as we move and what appears to be instructions for the player already provide elements for the key to the story.

The staging speaks more than any kind of cutscene could , indeed, these are really stripped down and only useful for introducing you to the games of the four characters to face.

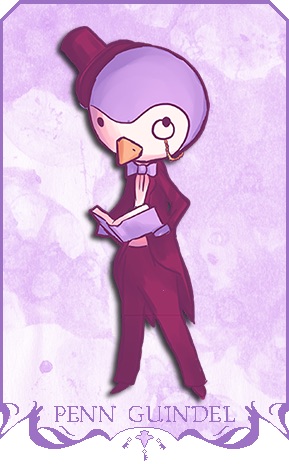

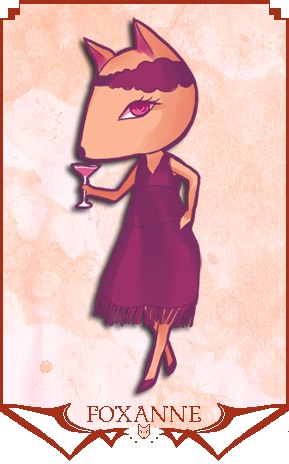

Do you see how the characters present themselves? They are extremely communicative with their designs already. Let’s start with the bunny, for example, who will limit herself to welcoming us (or rather, welcome back) and then immediately put us to the test with her minigame and the others will do the same.

There has already been a time when we talked about Dreaming Mary

We were comparing it to a title that did not present a minimum of directing effort in the scenes we were about to see, perhaps we were brazenly comparing two extremes.

Here we said, starting from the environments everything becomes a clue, it is the whole game that performs the communicative function .

Now the gameplay is divided into three major cycles. Play with Bunnilda, Foxanne, Penn Guindel and then go to Boaris, repeat this flow one more time until the third game gets harder. Then the infringement must be completed and you enter the picture that leads to the world of nightmares, where all the solutions to the games are found and you will have to escape from a threatening shadow.

Then after winning these, collect the seeds and keys (in the nightmare area) that will lead you to the final pursuit that will awaken you in reality where Mari will find the key to be able to get out of the room where she was locked up by her father.

You have noticed, right? There is no cutscene. There is no need to introduce characters, specific contexts, narrative arcs. That’s why I reaffirm convinced that the narration is the gameplay , an even more sophisticated and subtle coordination than the Mad Father gameplay functionality in which there was still a sort of division between cutscenes and gameplay.

We know the father as an antagonistic and abusive figure:

- Through the conversations with Boaris

- By shadow you run away from in a chase

- From the room where Mari wakes up showing us her sad situation.

There are, for example, no cutscenes in which the character is presented to you as happens in Cloé’s Requiem which we will discuss, another title that adopts linear narrative. We do not have the presentation of the character as such as happens in titles such as Angels of Death or Midnight Train, the presence of the father figure is articulated as a threatening aura that takes different forms, from Mari’s dreams to her nightmares and is never even shown to us in reality .

The game is really very explicit in its intentions without ever having to disturb a wall of text and in general without ever resorting to dialogue . The dialogues we have are captured in their essential form, what matters is everything around them, in fact it is difficult to dissect Dreaming Mary into scenes and appreciate only one over the other, the whole game is considered in its essence.

A small masterpiece in the field not only of the Horror RPG video game but I would venture to say in the field of the entire videogame narrative, a type of playful interweaving so brilliant that I have only seen it overcome for a short time by Body Elements .

There are many games that, especially from Generation 0, have tried to communicate only with their “very essence” (music, style, gameplay breakdown) and are among the titles for which I nurture my deepest esteem and admiration: Faust’s Alptraum , Body Elements and then there’s Dreaming Mary. The latter title managed to close perfectly and with great ingenuity a narrative plot that risked never ending or not explaining anything as happened for the other two titles, whose symbolism has taken a turn, overwhelming the importance of “ have something to say ”.

We know that Mary has to act in her dreams and the reason is explained towards the end, the endings of the game do not take deviations from an already decided linear path but deepen the sense of danger of the environment when we see the little girl fall down into her nightmares.

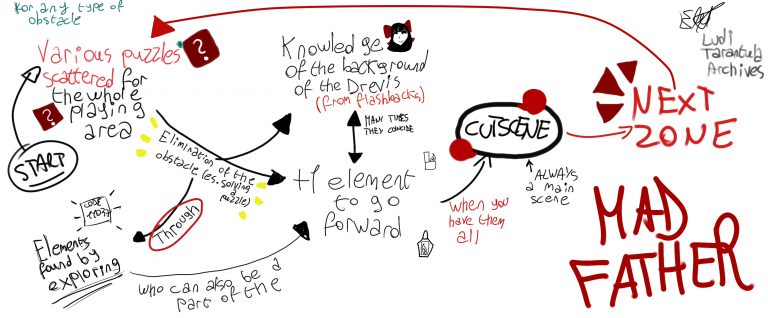

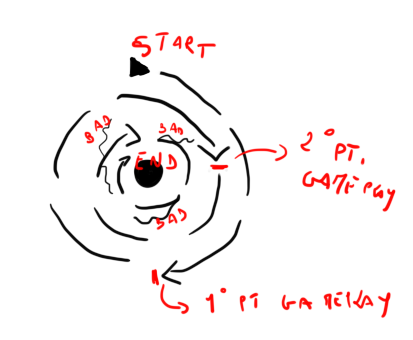

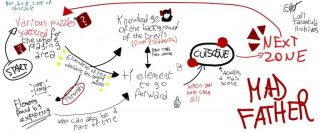

Let’s show a possible narrative scheme of Dreaming Mary and compare it with Mad Father:

Here is the scheme: the narrative continues like a spiral, the dotted lines correspond to the minigames that the characters propose to us three times up to the final part that exposes the protagonist’s objective…

Do you see how different they are? These are all the potentials that can be extracted without necessarily following a standard approach.

I want to conclude this first part with a consideration before moving on to the next title: Dreaming Mary is the only one of these three cases that not only shows an alternative technique to linear narration (“narration is gameplay” , absence of descriptive cutscene or based on linear events) but above all it demonstrates the theme of complementarity . The staging of any audiovisual product can and must act as a complementary feature to the linear narrative thus enriching the meanings of what the main plot shows us .

The genius of this title lies precisely in having based its narrative only on this.

Now let’s finally move on to the next game that-

So yes, Cat in the Box , a game to which we will also dedicate a review. But why talk about it in this space?

Let’s look at it for a moment: it doesn’t even have such a homogeneous aesthetic! The maps compared to those drawn by Dreaming Mary are pure gray stones set with excessive brightness!

We could mention for a moment the lines above on paratexts and packaging in general, it does not seem a title absolutely aimed at a large target and even less at a target of potential spectators as well as players.

Yet Cat in the Box blew me away. Let’s see why together.

Cat in the box – Looking for clues

This game is all that was needed, reaching the state of nirvana where you finally see what Generation 0 can promise in terms of narrative techniques .

There is a resumption of linearity and this phenomenon of “Generation 0 in modern times” we had already mentioned in Purgatory.

The protagonist to whom we will assign the name wants to leave the abandoned structure in which she sneaked in to impress the web. With an excellent diegetic expedient (speaking to a video camera), we learn that the place where she infiltrated belonged to a Masonic company that was arrested a few days ago.

We also know, in the course of the game experience, that the sect has managed to evoke an ancient divinity that we could define as the cause of all the supernatural facets of the title.

Perhaps following this whole series of information, you would think that a long story with dramatic tones lies ahead, which perhaps like Corpse Party starts from the events of the protagonists to extend attention to the background … But no.

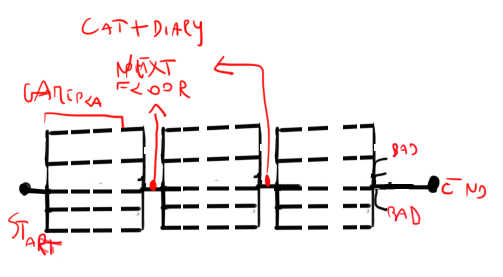

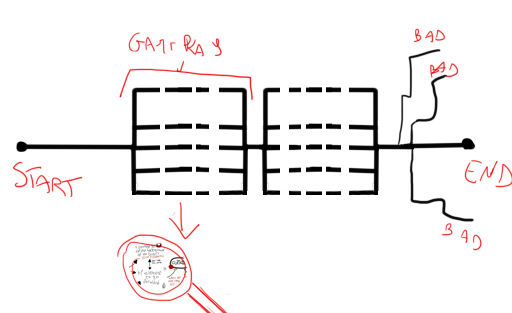

Let’s see together the narrative scheme that the title proposes:

The parallel dotted lines are the actions we perform in the gameplay while the vertical lines indicate some major discoveries.

So here is a rather short straight line from which many parallel lines start that join towards an end point, a term, not towards a conclusive narrative line. The dotted lines as we have done so far represent the actions that we are going to perform with the girl and that join towards a point that would be the end, these follow a linearity that lead to a speech , we want to communicate something specific that materializes in the final image . We can see the difference of this approach with what was with titles like Akemi Tan where there was only linearity in the gameplay with cutscenes to fill the clues, here instead it’s all based about exploration and the elements you find .

We do not have cutscenes in the classic sense of the term even in this second analyzed case. We are presented with the suspense against an unknown presence in the house, but also the scene in which we learn who this presence is is a clue like any other within the plot branch, We never a melodramatic approach that just wants to suggest an intention to tell a story. In this you will understand that is also different from The Witch’s House .

The “cutscene” pauses are certainly shorter than Mad Father’s (well, in the diagram I should have drawn longer lines for Mad Father). The point is that in The Witch’s House, however, there was a background that was then brought to the foreground . In Cat In The Box you don’t have this, there is never a real decisive cutscene in which all the weight and the meaning of the story shifts , the only one there is just a clue as were the other clues of the game….

…That combined with the CG shown in the finale perfectly closes the narrative framework (this one comes from the end where our protagonist escaped from the house).

We see the creature appearing during the chases that happen in the nightmares of the girl, that we spoiled on Twitter, for example.

It is not an unexplained phenomenon or left to itself, we could easily interpret it as all the spirits of the girl who in the other timelines have died in the structure and are now trying to possess the body in the present. Such content would have been treated as an extremely dramatic reveal in other narrative titles, not here. They just exist, they only seem to have the function of “monsters chasing you” until the final scene and the image that concludes the title serve as an explanation that allows you to fit all the pieces of the puzzle together.

We could define it as a title that has applied very well and in its own way the lessons we learned from Dreaming Mary: the gameplay phases coincide with the in-depth narrative that the protagonist faces through our control in the exploration phases.

And where is the ingenious move in all of this?

The sobriety . Indeed, the structure. Pure and simple structure that is bared in front of us showing us how it supports the build-game .

The staging does not lend itself much to a communicative function for the title neither with the maps nor with the direction that seems to distance itself from the events and to be very very dry, and that is why the clues you discover assume fundamental importance in the tell the story within the game. Everything happens not “during the exploration phase” but only during the exploration phase , the I consider almost virtuous the way in which the clues have been released and linked together without ever making too much prevail over each other, in fact all the elements of the story are given the same importance until there let’s compare with the answer to the question that the title wanted to launch from the introduction, closing as Dreaming Mary with a message expressed by an excellent circular narrative structure in which the ending matches and responds to prefaces that were made at the beginning.

Dear Red – Ramification to the extreme

So, let’s get back to us. Here I promised to speak of three methods alternative to linear fiction. Gentlemen, the one that breaks the mold the most in this sense is definitely Dear Red and takes up the theme of our preface: the endings .

But this title doesn’t do it like the others.

Thus, there are various methods of considering a Horror RPG with multiple endings. These can be a minor alternative to the main line as in Mad Father and numerous other narrative titles, diversifications on the knowledge a player has about a story as in The Witch’s House , events for their own sake as in Hello Hell … or? or The Dark Side Of Red Riding Hood before reaching the finale or, as in Dear Red a way to broaden the knowledge of the background .

I’m certainly not the first person to notice the potential of the method that Sang Gameboy has chosen to tell his story. Here, too, the use of introducing the title with a short sentence that serves as an introduction: otherwise we know very little about the girl when she is in front of the door with the intention of killing her parents’ killer.

A story is not ending, a story is starting.

The actions that can be performed lead us to different scenarios that make us discover a new piece of history. There is no real ending or the right one to go through, if not discovering the one that deepens the plot the most.

The technique has not been deepened enough and that is why the paragraph on this game is likely to be short. But it does not surprise me that the product has had a well deserved success, this is because the method that he has discovered has so much potential and if mixed with others, perhaps combined with a type of linear narrative, it could offer many opportunities to create possible masterpieces.

…………

[1] As any manual says: Events happen in reaction to something.

RPG Horror e Storytelling – Tre modi alternativi per raccontare una storia!

L’inverno sta arrivando.

E proprio perché sta arrivando ecco che torna quell’attività che tutti sogneremmo di fare almeno una volta nella vita: ascoltare storie davanti al caminetto, sopratutto quando hanno a che fare con il mondo del mistero!

Ele: Credevo che quello che piace di fare di più di inverno fosse strafogarsi di cioccolata calda e dormire sotto le coperte.

Pao: Non dovevo occuparmi io di questo articolo?

Ele: Avevo pensato di fare un salto per salutare i ragazzi.

Ele: *Ciaaao ragazzi.*

Pao: Sparisci di qui.

Dunque, avrete capito di che sto parlando, ma certo, dello storytelling nell’ambito degli RPG Horror! Beh del resto era anche il titolo dell’articolo. Sì.

Cosa dire, abbiamo iniziato la stagione di quest’anno con un sacco di premesse e discussioni ma finalmente potremo iniziare a riprendere assieme gli approcci un po’ più teorici, nell’articolo su Purgatory me l’ero malamente data a gambe…Non vedevo l’ora!

Quali sono le premesse per questo articolo?

Tanto per cominciare l’avviso che vi propongo è che non sono una studiosa dello storytelling videoludico. Tutto quello che dirò in questa sede è basato soltanto sull’osservazione che ho avuto modo di fare durante la mia esperienza con gli RPG Horror.

Quello che ho notato in via generale, da ignorante in materia è stato considerare come da un lato nel mondo dei videogiochi la narrazione non solo non sia mai stata un elemento per cui il media si è contraddistinto ma sia anche scarsamente considerata la complessità di un intreccio narrativo, senza parlare poi della questione dei finali multipli. Non è solo nell’ambito dell’RPG Horror o nei titoli giapponesi come le varie visual novel e i modelli delle route, anche molti titoli occidentali sembrano sfruttare questo metodo. A naso potrei citare titoli come Detroit: Become Human che si basano su numerosi finali a seconda delle scelte di gioco. Molti l’hanno considerata come un’operazione ammirevole e da elogiare, posso capire il perchè, ma c’è un ma.

Mi sembra una mossa “fin troppo comoda”. Quello che mi chiedo è quanto valga la pena scaglionare la responsabilità di affidare al giocatore l’andamento di una storia, la vedrei come una scusa per non prendere mai una decisione definitiva. Tralasciando i casi in cui la storia è lineare e tecnicamente solo un finale è giusto ne approfitto di questa premessa per affermare che il tema dei finali è l’ultima cosa di cui ci preoccuperemo in questo articolo.

So che era necessario dirlo, perché è una delle caratteristiche chiave ormai per cui l’RPG Horror è conosciuto, anzi, una delle poche formalità in campo narrativo per cui il genere è riconosciuto.

Facendo un breve re-cap storico cerchiamo di ricordarci uno degli elementi chiave di questo genere: gli indizi inerenti la storyline si scoprono durante la fase esplorativa che spesso si distanzia rispetto alla parte di una storia in cui si assistono a delle cutscene. Bene.

Poi ricorderemo che Mad Father ha introdotto e fatto riconoscere al pubblico le basi della narrazione lineare in cui la scoperta degli indizi di una storia sono strettamente circoscritti ad un preciso contesto. Ha introdotto, ricordiamo, alla perfezione il tema della narrazione lineare in un ambito tanto largo come quello videoludico in cui è tutto nelle mani del giocatore.

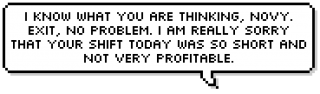

Ripassiamo per un attimo questo concetto, vi lascio qui questo schema.

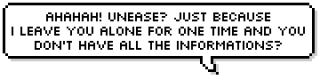

…Ahem.

Pao: Si, mi servirebbero carta e penna ma non li trovo…

Libreria: Ecco il tuo schema!

Pao: Ah! Ma da dove diavolo..Che cosa…

Libreria: Avevo visto che lo stavi disegnando, quindi ho pensato di finirlo io!

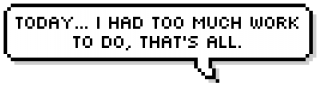

Libreria: Forse eri tanto impegnata che non potevi finirlo…

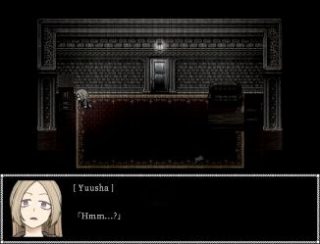

Pao: Ah..Grazie! Davvero un ottimo lavoro.

Libreria: “E ho anche qui tutti e tre gli screen richiesti per l’incontro di oggi”

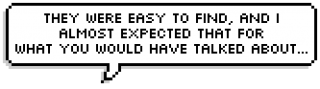

Libreria: E’ stato molto semplice trovarli e quasi mi sarei aspettata per il discorso che avreste dovuto fare…

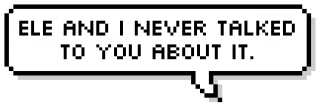

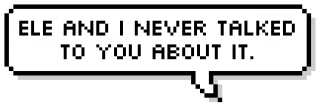

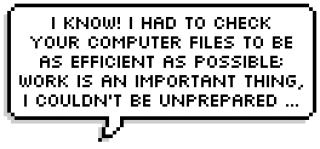

Pao: Ma te ne abbiamo mai parlato.

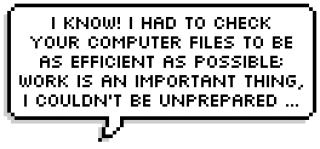

Libreria: Lo so! Ho dovuto controllare i file del tuo computer! il lavoro è una cosa importante, non potevo essere impreparata…

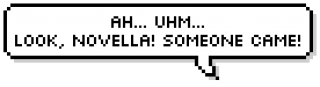

Pao: Ah-ehm. Guarda, Novella, è arrivato qualcuno!

Libreria: Eh? Ah!

Ecco, brava signorina, torna tranquilla tranquilla a lavorare.

Dunque, sì, la nostra asisstente ha velocizzato un po’ troppo le cose, dei tre screen ce ne occuperemo più tardi…

Piuttosto vediamo lo schema che propone prima di concludere il discorso su Mad Father.

Abbiamo la linea narrativa unica, le linee parallele tratteggiate che vedete sono tutti quegli indizi e flashback che si trovano in maniera sparsa durante il gioco, ma poi come potete vedere si riconducono ad un’unica linea narrativa che non smette mai di essere unica e stabile e basata sul rapporto causa-effetto[1], una caratteristica che si contraddistingue già dal fatto che la fase di gameplay a livello di azioni e comprensione della storia è comunque spearata rispetto alle “grandi scene” che portano avanti la trama. E questo va avanti fino all’atto finale, per esattezza il raggiungimento del breakpoint in cui i finali si diramano solo nell’ambito del climax conclusivo, queste linee come potrete vedere si sposano bene con lo schema sul gameplay libero che Ele aveva fatto nell’articolo dedicato a Mad Father.

….Quindi….Tornando al nostro schema….

Come potete vedere ho segnato i finali con delle linee più sottili per indicare lo scarso impatto sulla linea narrativa principale, il gioco fa capire molto bene la strada scelta. I vari “bad end” sono diverse conseguenze a tipi di eventi, non stravolgono i caratteri dei personaggi.

A questo punto del discorso dovrete aver capito una cosa: la narrazione a cui sto facendo riferimento rimanda unicamente al testo. Il testo è il gioco stesso e si legge, comprende e interpreta proprio come si legge una frase.

Quello che faremo in Back to the future non appena riprenderemo in mano la rubrica sarà confrontare il testo con i paratesti. In realtà lo facciamo già, parliamo dei paratesti ogni qualvolta parliamo del packaging, ma adesso potrete rendervi conto di quanto il rapporto tra testo e paratesto sarà estreamente importante per la generazione dello storytelling, Pocket Mirror ha incontrato proprio una collisione tra questi due elementi per esempio, causando un calo di un certo tipo di aspettative da parte del pubblico; sono incidenti di percorso che si possono incontrare nell’ambito della realizzazione di un prodotto audiovisivo. Sarà una delle tante parentesti che apriremo sullo storytelling perché l’arte della narrativa nel mercato dell’audiovisivo è strettamente legata alla sfera produttiva, quindi sarà inevitabile considerare il contesto e le intenzioni produttive influiscono notevolmente sul linguaggio adottato dalla narrazione di una storia.

Abbiamo avuto in Corpse Party un ottimo esempio, dalla versione del ’96 realizzata per un contest da un autore indipendente si limita a concentrare le informazioni nel finale al fine di mettere in primo piano l’esperienza di gioco, mentre nella versione in seguito commercializzata la priorità è categorizzare i personaggi ed espandere in maniera più deterministica e chiara gli indizi sulla trama: prendiamo ad esempio la morte di Sachiko, l’esempio più evidente. Nel ’96 viene riassunta in un wall of text, nel suo alter ego commerciale viene mostrata per poter essere chiara e comprensibile a più utenti possibili.

Quindi, dopo aver concluso anche la nostra parentesi, perché allora proponiamo questo articolo? Perché parlare di tecniche alternative alla narrazione lineare?

Cerchiamo di riprendere un concetto citato in Mad Father.

Anche se la linearità permette di avere certamente un’audience più ampia e potenzialmente interessata ad una storia ciò non toglie il potenziale interesse del pubblico per la ricerca di uno stile narrativo più sofisticato (ad esempio con la costruzione di sottotesti) che possa essere utilizzato non solo come stile di narrazione alternativo ma anche come una linea narrativa complementare alla trama principale.

Conclusa finalmente la nostra lunga premessa…

…Possiamo finalmente iniziare a parlare dei tre modi adottati dagli RPG Horror per proporre una storia!

Pao: Si lo so, finalmente ci siamo arrivati. Sapete, e che questi discorsi li faccio sempre da sola o con Ele e…

Pao: Insomma, diciamo che vomitarli tutti in una volta per un articolo è stata un’esperienza liberatoria.

Libreria: Oh, ti capisco, anche io sono sempre sola

Pao: Ho appena detto che ne parlo anche con El-

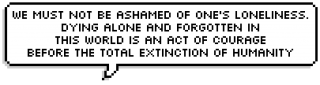

Libreria: Non bisogna vergognarsi della propria solitudine, morire soli e dimenticati in questo mondo è un atto di coraggio prima della totale estinzione dell’umanità.

Pao: …Cerchiamo di capire piuttosto da dove iniziare.

Dreaming Mary – La narrazione è il gameplay

…Ma cos’è questa musica che sento?

Certamente quella del titolo di Dreaming Mary!

Difatti non potrebbe che essere il titolo migliore di cui iniziare a parlare. Vedete come i disegni e i colori sono usati per creare fin da subito un immaginario molto molto forte?

Comincerò con questa azzardata affermazione: Dreaming Mary non ha una linea narrativa, lo storytelling “non esiste” in questo gioco. L’ambiente e le fasi di gameplay coincidono con la storia a tal punto che diventano la vera forma di narrazione.

Cerchiamo di ricordarci come inizia.

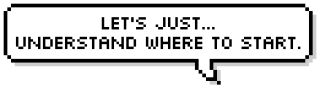

Lirbreria: Ecco il suo screen-sign! Oh ma che ragazzina adorabile!

Ecco la piccola Mary. La prefazione, ovvero le scritte in cielo che appaiono, è davvero corta, il cuore della narrazione è tutto nel gameplay da questo punto in poi.

Dunque, dicevamo che lo storytelling qui “non esiste” ma non vuol dire che non ci sia una storia come voleva essere per Ao Oni ad esempio. La radio parla mentre ci muoviamo e quelle che sembrano istruzioni per il giocatore già forniscono elementi per la chiave di lettura della storia.

La messa in scena parla più di quanto potrebbe farlo qualsiasi tipo di cutscene, anzi, queste sono davvero ridotte all’osso e utili solo per introdurti i giochi dei quattro personaggi da affrontare.

Vedete come si presentano i personaggi? Sono estremamente comunicativi già con i loro design. Cominciamo dalla coniglietta per esempio, che si limiterà a farci convenevoli di benvenuto (anzi, bentornato) e poi ci metterà subito alla prova con il suo minigioco e allo stesso modo faranno gli altri.

C’è stata già un’occasione in cui abbiamo parlato di Dreaming Mary

La stavamo mettendo a confronto proprio con un titolo che non presentava un minimo sforzo di regia nelle scene che ci apprestavamo a vedere, forse stavamo sfacciatamente mettendo a confronto due estremi.

Qui dicevamo, già a partire dagli ambienti tutto diventa un indizio, è il gioco intero a svolgere la funzione comunicativa.

Ora il gameplay si articola in tre grandi cicli. Gioca con Bunnilda, Foxanne, Penn Guindel e poi vai da Boaris, ripeti questo flusso un’altra volta finché la terza i giochi non si faranno più difficili. Allora va compiuta l’infrazione e si entra nel quadro che porta nel mondo degli incubi, dove si trovano tutte le soluzioni ai giochi e dovrai scappare da un’ombra minacciosa.

Allora dopo aver vinto a questi raccogli i semi e le chiavi (nella zona degli incubi) che ti porteranno all’inseguimento finale che ti faranno risvegliare nella realtà dove Mari troverà la chiave per poter uscire dalla stanza dove era stata rinchiusa da suo padre.

Ve ne siete accorti, no? Non c’è alcuna cutscene. Non c’è bisogno che si presentino personaggi, contesti specifici, archi narrativi. Ecco perché riaffermo convinta che la narrazione è il gameplay, un coordinamento ancora più sofisticato e sottile rispetto alla funzionalità del gameplay di Mad Father in cui c’era comunque una sorta di divisione tra cutscenes e gameplay.

Noi conosciamo il padre come figura antagonista e abusiva:

- Tramite i dialoghi con Boaris

- Tramite ombra da cui scappi via tramite un inseguimento

- Dalla stanza in cui Mari si risveglia mostrandoci la sua triste situazione.

Non ci sono, ad esempio, cutscene in cui ti viene presentato il personaggio come accade in Cloé’s Requiem di cui parleremo, un altro titolo che adotta la narrazione lineare. Non abbiamo la presentazione del personaggio come tale come avviene in titoli qual Angels of Death o Midnight Train, la presenza della figura paterna si articola come aura minacciosa che prende diverse forme, dai suoi sogni ai suoi incubi e nemmeno ci viene mai mostrato nella realtà.

Il gioco è davvero molto esplicito nelle sue intenzioni senza mai dover scomodare un wall of text e in generale senza né mai ricorrere ai dialoghi. I dialoghi che abbiamo sono colti nella forma essenziale, ciò che conta è tutto quello che c’è attorno, difatti è difficile sezionare Dreaming Mary in scene e apprezzarne solo una rispetto all’altra, tutto il gioco viene considerato nella sua essenza.

Un piccolo capolavoro nell’ambito non solo del video gioco RPG Horror ma azzarderei a dire nel campo dell’intera narrazione videoludica, un tipo di intreccio ludico tanto geniale che ho visto solo superare per poco da Body Elements.

Ci sono tanti giochi che, soprattutto da parte della Generazione 0, hanno cercato di comunicare soltanto con la loro “stessa essenza” (musiche, stile, scioglimento del gameplay) e sono tra i titoli per cui nutro la mia più profonda stima e ammirazione: Faust’s Alptraum, Body Elements e poi c’è Dreaming Mary. Quest’ultimo titolo è riuscito a chiudere perfettamente e con grande ingegno un intreccio narrativo che rischiava di non chiudersi mai o non spiegare nulla come è accaduto per gli altri due titoli, il cui simbolismo ha preso piega sovrastando l’importanza dell’ “aver qualcosa da dire”.

Sappiamo che Mary deve agire nei suoi sogni ed il motivo viene esplicitato verso la fine, i finali del gioco non prendono deviazioni da una strada lineare già decisa ma approfondiscono il senso di pericolo dell’ambiente quando vediamo la piccina cadere giù nei suoi incubi.

Mostriamo un possibile schema narrativo di Dreaming Mary e confrontiamolo con quello di Mad Father:

Ecco lo schema: la narrazione prosegue come una spirale, la le linee tratteggiate corrispondono ai minigiochi che i personaggi ci propongono per tre volte fino ad arrivare alla parte finale che espone l’obiettivo della protagonista…

Vedete quanto sono diversi? Queste sono tutte le potenzialità che si possono estrarre senza dover seguire per forza un approccio standard.

Voglio concludere questa prima parte con una considerazione prima di passare al prossimo titolo: Dreaming Mary è l’unico di questi tre casi che non solo mostra una tecnica alternativa alla narrazione lineare (“la narrazione è il gameplay”, assenza di cutscene di stampo descrittivo o basata su eventi lineari) ma soprattutto ci dimostra il tema della complementarità. La messinscena di un qualsiasi prodotto audiovisivo può e deve fungere da caratteristica complementare alla narrazione lineare arricchendo così i significati di ciò che la main plot ci mostra.

La genialità di questo titolo sta proprio nell’aver basato la sua narrazione solo su questo.

Ora passiamo finalmente al prossimo gioco che-

Ele: Io! Voglio proporre io!

Pao: Ah sì?

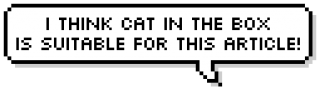

Ele: Penso che Cat In The Box ci stia bene per l’articolo!

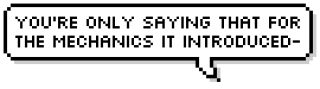

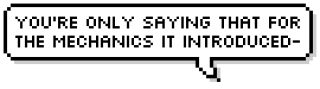

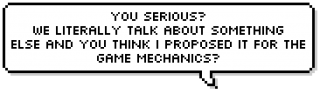

Pao: Lo dici per caso solo per le meccaniche che ha introdotto?

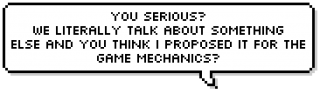

Ele: Sei seria? Parliamo totalmente di qualcos altro e pensi che l’abbia proposto per le meccaniche?

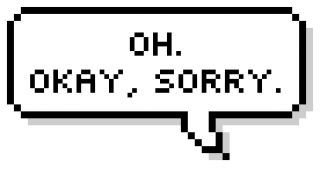

Pao: Oh. Okay, scusami.

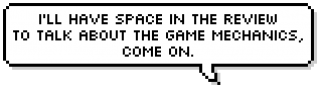

Ele: Avrò spazio nella recensione per parlare delle meccaniche di gioco, e dai.

Pao: D’accordo, okay, scusa…

Ele: Mi hai davvero deluso.

Paola: Ho detto che mi spiace.

Dunque sì, Cat in the Box, un gioco a cui dedicheremo anche una recensione. Ma perché parlarne in questo spazio?

Guardiamolo un attimo: non ha nemmeno un’estetica così omogenea! Le mappe a confronto di quelle disegnate da Dreaming Mary sono pure pietre grigie messe ad un livello di brightness troppo alto!

Potremmo accennare per un momento al discorso di prima sui paratesti e in genere sul packaging, non sembra un titolo assolutamente rivolto a un largo target e ancora di meno ad un target di potenziali spettatori oltre che giocatori.

Eppure Cat in the Box mi ha spiazzato. Vediamo insieme il perché.

Cat in the box – Raccolta di indizi

Questo gioco è tutto quello di cui c’era bisogno, il raggiungimento dello stato del nirvana in cui si vede finalmente cosa la Generazione 0 può promettere in termini di tecniche narrative.

C’è una ripresa della linearità e questo fenomeno della “Generazione 0 nei tempi moderni” l’avevamo già accennata in Purgatory.

La protagonista a cui assegneremo il nome vuole uscire dalla struttura abbandonata in cui si è introdotta furtivamente per fare colpo sul web. Con un ottimo espediente diegetico, ovvero parlando ad una videocamera, veniamo a sapere che il luogo in cui si è infiltrata apparteneva ad una società massonica che è stata arrestata pochi giorni fa.

Sappiamo anche, nel corso dell’esperienza di gioco, che la setta è riuscita ad evocare una divinità antica che potremmo definire come la causa di tutte le sfaccettature sovrannaturali del titolo.

Magari a seguito di tutta questa serie di informazioni pensereste che si prospetta una storia lunga e con toni drammatici, che magari come Corpse Party parte dalle vicende dei protagonisti per estendere l’attenzione sul background…E invece no.

Vediamo insieme lo schema narrativo che propone il titolo:

Le linee tratteggiate parallele sono le azioni che compiamo nel gameplay mentre le linee verticali indicano alcune scoperte principali.

Quindi ecco una linea retta piuttosto corta da cui partono tante linee parallele che congiungono verso un punto finale, un termine, non verso una linea narrativa conclusiva. Le linee tratteggiate come abbiamo fatto finora rappresentano le azioni che andiamo a compiere con la ragazza e che congiungono verso un punto che sarebbe il finale, queste seguono una linearità che portano ad un discorso, si vuole comunicare qualcosa di preciso che si concretizza nell’immagine finale. Possiamo vedere la differenza di questo approccio con quello che c’era con titoli come Akemi Tan in cui c’era solo linearità nel gameplay con delle cutscene per colmare gli indizi, qui invece è tutto basato sull’esplorazione e gli elementi che trovi.

Non abbiamo delle cutscene nel senso classico del termine nemmeno in questo secondo caso analizzato. Ci viene presentata la suspense nei confronti di una presenza sconosciuta nella casa, ma anche la scena in cui si viene a conoscenza di chi questa presenza sia è un indizio come un altro all’interno della diramazione della trama, non abbiamo mai un approccio melodrammatico che voglia anche solo suggerire l’intenzione di raccontare una storia. In questo potrete ben capire che è diverso anche da The Witch’s House.

Le pause “per le cutscene” sono certamente più corte rispetto a quelle di Mad Father (beh, nello schema avrei forse dovuto disegnare quelle linee più lunghe in Mad Father). Il punto è che in The Witch’s House comunque c’era un background che poi è stato portato in primo piano. Qui no, non c’è mai una vera e propria cutscene risolutiva in cui si sposta tutto il peso e il significato della storia, l’unica che c’è è solo un indizio come lo sono stati gli altri indizi del gioco.

…Che uniti alla CG mostrata nel finale chiudono perfettamente il quadro narrativo (questa si trova nel finale in cui la protagonista riesce a scappare dalla casa).

Vediamo la creatura che appare durante gli inseguimenti che avvengono nei suoi incubi che avevamo spoilerato su Twitter, ad esempio.

Non è un fenomeno inspiegato o lasciato a se stesso, potremmo facilmente interpretarlo come tutti gli spiriti della ragazza che nelle altre linee temporali sono morte nella struttura e ora cercano di possedere il corpo nel presente. Un contenuto del genere sarebbe stato trattato come una reveal estremamente drammatica in altri titoli narrativi, qui no. Loro esistono e basta, sembrano avere solo la funzione di “mostri che ti inseguono” finché la scena finale e l’immagine che conclude il titolo non fungono da spiegazione che ti permette di incastrare tutti i pezzi del puzzle.

Potremo definirlo un titolo che ha applicato egregiamente e a modo suo gli insegnamenti che abbiamo tratto da Dreaming Mary: le fasi di gameplay coincidono con l’approfondimento narrativo che la protagonista affronta tramite il nostro controllo nelle fasi di esplorazione.

E dov’è la mossa geniale in tutto questo?

La sobrietà. Anzi, la struttura. Purissima e semplice struttura che si denuda davanti a noi mostrandoci come sostiene egregiamente l’edificio-gioco.

La messa in scena non si presta molto ad una funzione comunicativa per il titolo né con le mappe né con la regia che sembra prendere le distanze dagli eventi ed essere molto molto asciutta, ed è per questo gli indizi che scopri assumono un’importanza fondamentale nel raccontare la storia all’interno del gioco. Il tutto avviene non “durante la fase d’esplorazione” ma solo durante la fase d’esplorazione, lo considererei quasi virtuoso il modo in cui sono stati rilasciati gli indizi e concatenati tra loro senza mai far prevalere troppo l’uno sull’altro, difatti a tutti gli elementi della storia viene fornita la stessa importanza finché non ci confrontiamo con la risposta alla domanda che il titolo voleva lanciare dall’introduzione, chiudendosi come Dreaming Mary con un messaggio espresso da un’ottima struttura narrativa circolare in cui il finale combacia e risponde alle prefazioni che sono state fatte all’inizio.

Pao: Anche se avrei una riflessione da fare su questo gioco e cioè come sembra spostarsi su quella che è un’estetica “più occidentale”, per vedere come si differenzia negli stili. Insomma, sono coreani ma… Sia i due autori che la società distributrice sembrano piuttosto orientati all’estero…

Ele: Heeeeey, avremo una recensione per parlare di questo aspetto.

Pao: Sì, sì, lo so, era per dire. Mi sembrava solo strano notare come da “una parte del mondo” ci fosse più attenzione allo stile di un prodotto e alla sua estetica mentre “dall’altra parte” il focus sembri spostarsi sui meccanismi di gameplay e sulla struttura interna di un titolo anche a costo di sacrificare lo stile…Voglio dire…Le tendenze sembrano quelle.

Ele: Eh? Meccanismi di gameplay? Non si parlava di *storytelling* qui? Vuoi metterti a parlare di gameplay anche tu adesso?

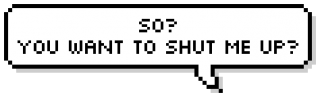

Pao: Quindi? Mi vorresti zittire?

Lib: Uh… Ehm…

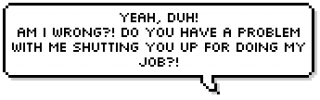

Ele: Assolutamente si! Ho per caso torto? Hai qualche problema se ti zittisco mentre fai il mio lavoro?!

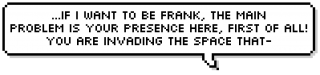

Pao: Se devo essere franca, il primissimo problema da considerare è che stai invadendo lo spazio che-

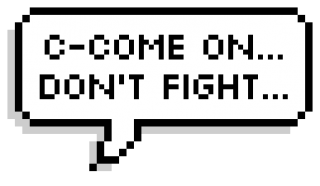

Libr: Su-Suvvia…Non è certo il momento di litigare…

Pao: …

Ele: …Comunque non ci provare più a-

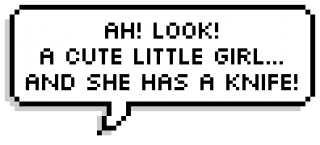

Libr: Ah! Guardate! Una simpatica ragazza con un coltello!

Ele: Woo… Ne dovevi parlare?

Pao: Si, ne dovevo parlare… Prima che mi interrompessi.

Libr: Vado a prendere il materiale…

Dear Red – La ramificazione all’estremo

Allora, torniamo a noi. Qui vi avevo promesso di parlare difatti di tre metodi alternativi alla narrativa lineare. Signori, quello che rompe più gli schemi in assoluto in questo senso è sicuramente Dear Red e riprende il tema della nostra prefazione: i finali.

Ma questo titolo non lo fa come gli altri.

Ele: Hm… Che casino.

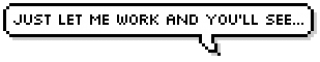

Pao: Lasciami lavorare e vedrai….

Dunque, ci sono vari metodi di considerare un RPG Horror a finali multipli. Possono essere questi un’alternativa minore alla linea principale come in Mad Father e numerosi altri titoli narrativi, delle diversificazioni sulle conoscenze che un giocatore ha su una storia come in The Witch’s House, degli eventi fini a se stessi come in Hello Hell…o? o The Dark Side Of Red Riding Hood prima di giungere al finale oppure, come in Dear Red un modo per allargare la conoscenza del background.

Sicuramente non sono la prima persona che nota la potenzialità del metodo che Sang Gameboy ha scelto per raccontare la sua storia. Anche qui non viene perso l’uso di introdurre il titolo con una breve frase che funge da introduzione ma per il resto sappiamo davvero poco della ragazza quando è di fronte la porta con l’intenzione di uccidere l’assassino dei suoi genitori.

Non si sta concludendo una storia, la si sta iniziando.

Le azioni da poter compiere ci conducono verso differenti scenari che ci fanno scoprire un nuovo pezzo di storia. Non c’è un vero e proprio finale o uno giusto da percorrere, se non scoprire quello che approfondisce di più la trama.

La tecnica non è stata approfondita a sufficienza ed è per questo che il paragrafo su questo gioco rischia di risultare corto. Ma non mi stupisce che il prodotto abbia avuto un buon successo del tutto meritato, questo perché il un metodo che ha scoperto ha davvero tante potenzialità e se mischiato ad altri, forse unito ad un tipo di narrazione lineare, potrebbe offrire tante opportunità per creare dei possibili capolavori.

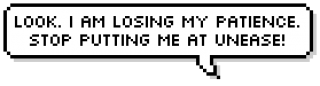

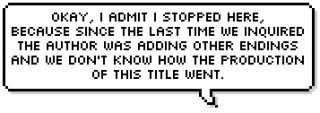

Pao: Okay ammetto che mi sono fermata qui, perché dall’ultima volta che ci siamo informate l’autore stava aggiungendo altri finali e non sappiamo com’è andata a finire la produzione di questo titolo.

Ele: Perché non dici che in realtà sei pigra e non avevi voglia di approfondire la versione Extended di Dear Red, quella che è su Steam?

Pao: Perché non è vero, non sapevo neanche che fosse stata effettivamente rilasciata la versione aggiornata del gioco!

Pao: …Sto perdendo la pazienza. Smettila di mettermi a disagio!

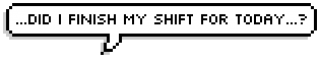

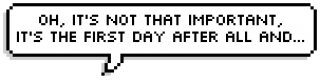

Libreria: Io..Ho finito il turno per oggi?

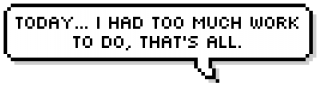

Ele: Ahahah! A disagio? Perché per una volta che ti lascio da sola non hai tutte le informazioni?

Pao: Oggi… Ho avuto fin troppo di cui occuparmi, ecco.

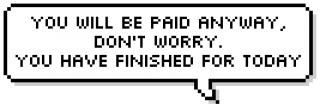

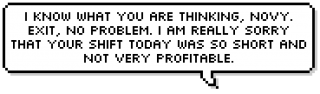

Ele: So cosa stai pensando, Novy. Vai pure, no problem. Sono davvero dispiaciuta che il tuo turno di oggi sia stato così corto e poco remunerativo

Libreria: Oh ma non è così importante, dopotutto è il primo giorno e…

Pao: Verrai retribuita ugualmente, non preoccuparti. Hai finito per oggi.

…………

Pao: …Sai cosa? Voglio proprio vedere come hai intenzione di portare avanti il tuo articolo la prossima volta.

Ele: Sicuramente non facendo cadere le braccia ai lettori con paragrafi e paragrafi di nozioni, su nozioni, su nozioni… Ugh!

Ele: Saprò catturarli sicuramente più di te!

Ele: Mmh… No, non dovrei dirlo io. Ragazzi, perchè non giudicate voi? Tenetevi aggiornati con il Ludi Tarantula Archives!

[1] Come dice qualsiasi manuale: gli eventi accadono in reazione a qualcosa.