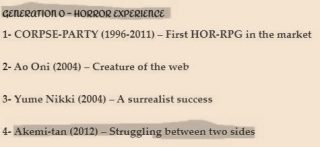

Welcome to Mogeko Castle, the only castle where you can be threatened by yellow cats and fight them with the power of prosciutto!

While the protagonist of the game goes to her last train stop, this is for us the last stop of the first generation with the time machine for “Back to the future”.

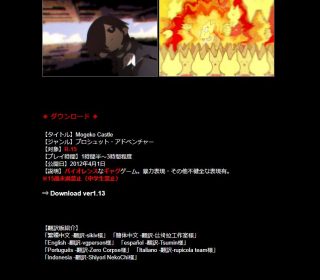

This title spread in 2014 and has been recognized as one of the most bizarre HOR-RPGs.

Some call it a parody of this current. Well, when a parody of something materializes, it means that the latter has developed elements that characterize it.

Let’s see together how the parodic RPG par excellence was born and raised.

Okay, this is one of the cases in which the various wikis on the game are fairly well-informed, and you don’t have to look for who knows what site to know the release date of Mogeko Castle in Japan: March 5, 2014 …

No, that’s wrong!

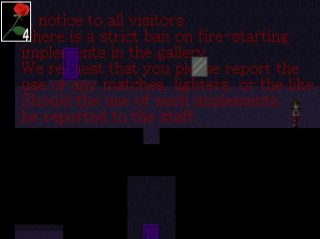

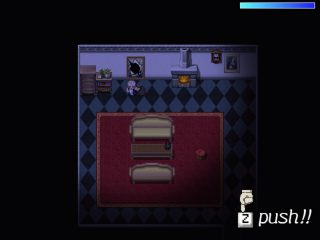

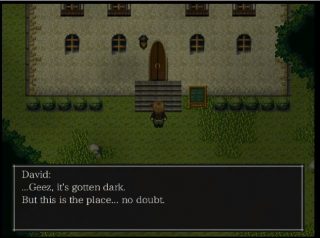

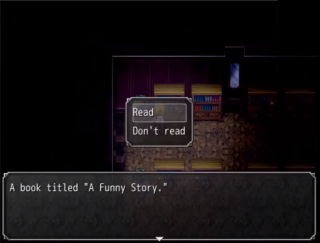

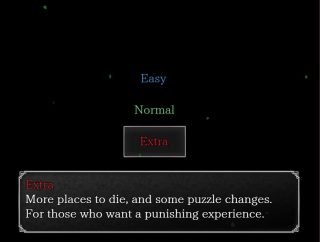

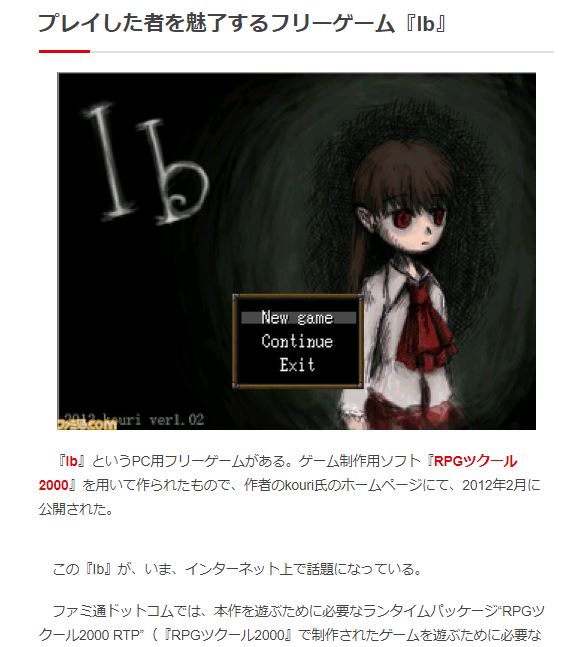

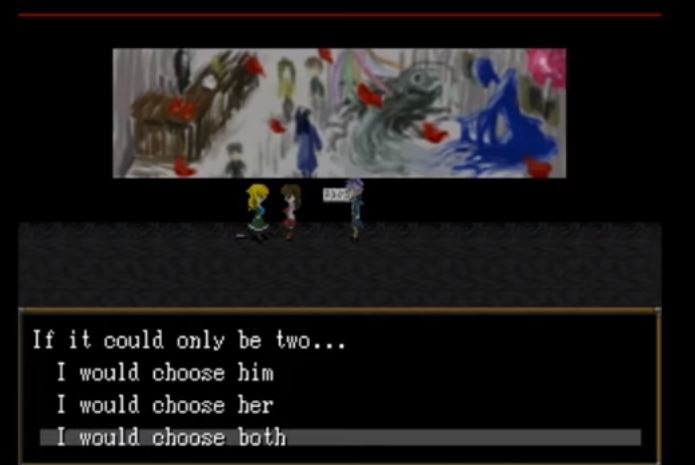

Do you recognize this game screenshot?

Remember the epic battles we all fought in Mogeko Castle?

No?

Of course you don’t remember them, because the wikis are also provided enough to tell us that the very first release of the game was on April 1st, 2012 (how ironic to release a parodic game on April 1st?), In a version made on RPG Maker 2000, untraceable today on official sites, which precisely as a substantial difference compared to the game we all played and seen on Youtube, had battles at certain moments of the game. So we should start the development history of Mogeko Castle from 2012

…If only it had something to offer.

It seems that only one channel, Alex Lu, has brought (even without any commentary) the first version of the game on youtube. Even in its homeland the game wasn’t well known, having perhaps even been less “publicized” by the author herself.

It would not even be such a risky hypothesis, given that as of today it is still not clear to me how the 2014 version was so well known both in Japan and in the West, given that it also had no advertising in Japan: I haven’t found other sites to download it, only the author’s site.

After having had its space, in one way or another, in the Japanese Horror RPG community, this title (or rather, its remake, having been even more popular in the community in general) was eventually discovered by our dear Kate (VgPerson) and translated into English. Needless to say, the usual gameplay rallies started from that translation as has happened with many other titles, but Mogeko Castle had different reasons for being popular in the world HOR-RPG community.

In these three comments we had three different types of reception for the game.

Surely there are those who have appreciated the various elements that we will analyze in the Ace in the Sleeve, as well as the most surreal elements of the game … And who has been even a minimum disturbed perhaps by the same strange elements that made other players laugh or bewildered ( of this type of comments and why they are not all like this, even if we know what the game is about, we will explain it better in the Ace in the Sleeve).

In general, however, the reception on the game has been very positive in the HOR-RPG community, due to a factor that we will explain below.

Mogeko Castle has joined three genres together: adventure, horror and demential.

The demential genre is generated to break traditional narrative schemes, to act as a parody. And in our case Mogeko Castle is a game out of the box of what has become over time a full-fledged current: it already had its clichés, elements of vague similarity between one game and another (let’s take the example of the classic girl protagonist), atmospheres, types of plots. A current already formed thanks to the two generations that we have already treated – mainly the first one, not the Generation 0- at this point needed a parody that would ridicule them with “dangerous” monsters that at the dinner time bell turn into ridiculous beings (this it also makes them very ambiguous to the player), strange customs and strange other characters that we will find in the castle in general, together with the situations we will face.

So how did Mogeko Castle made its way into the global HOR-RPG community?

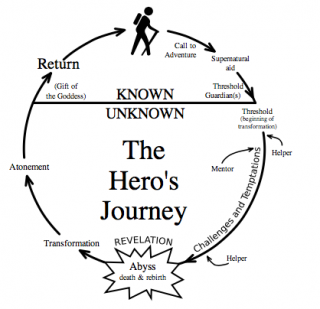

Mogeko Castle is first of all an adventure, it faces a journey in the true sense of the term (and not The Hero’s Journey we mentioned in the previous article): the goal of Yonaka is to find a safe exit from the castle, and in doing so he will come across all its different areas and varieties of inhabitants.

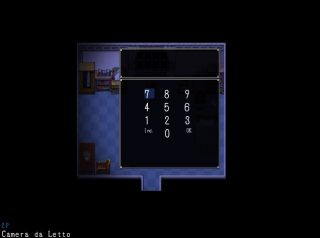

In this regard I would like to make a note on the gameplay of this game.

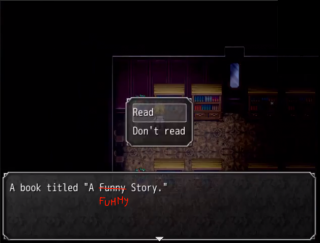

Although devoid of innovative mechanics, real puzzles (you only have a little difficulty in some pursuits, such as that of multiple doors) and in general enough if not much, lackluster, has an element that makes the game still enjoyable: interaction with the environment. In fact, we have many possibilities to interact, sometimes even in ways other than just talking, with the various types of Mogeko that we will meet, to activate mechanisms in the castle (although in many cases they will cause a game over or a bad end) or even simply collect items to the right and left, among vomit-filled rubbish bags to “fluffy books”.

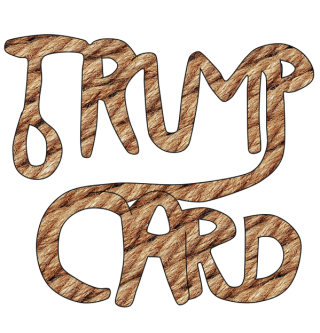

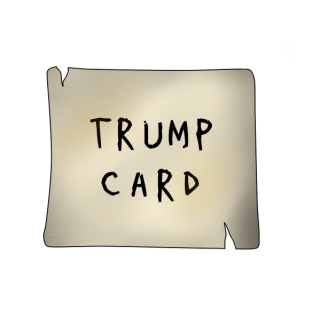

Going instead from the narrative point of view of the game, given that the gameplay does not really offer anything, to be honest, during the History of the Product we talked before about the wide sphere of emotions that this title has provoked in gamers. This turns out to be its main Trump Card.

More precisely, the main strength of Mogeko Castle is the multitude of used registers and the management of them.

Above we said that this title is a demential adventure, right?

…Absolutely

In the game we can remember these types of scenes, present above all at the beginning of the game but which are distributed for almost its entire duration, but also…

Not to mention the numerous and sometimes disturbing Bad Ends.

In short, if we talk about atmospheres and, as mentioned above, registers, Mogeko Castle really has everything. But how have all these different registers been managed to make them a Trump CArd, and not simple vibe inconsistencies that would have gone straight into the Work Defects? Let’s examine the three basic registers one by one.

-Demential Register.

As mentioned above, it is the predominant register in many parts of the game, especially at the beginning.

It’s pretty much what players came up with and are still fascinated by. I would like to speak in these paragraphs of the “style” of Mogeko Castle’s demential moments with regard to the situations and the background presented, comparing it with various Japanese works that may come close to the comedy of this title.

Let’s start by narrowing the field of action, and concentrating on demential works from a specific land: Japan. This is simply because Mogeko Castle greatly embraces the typical Japanese comedy which, in fact, relies heavily on demential. If you take any Japanese fictional work (but also many television games, the most popular, Takeshi’s Castle) many comic moments always have a demential nuance or simply leave the viewer glued to the screen just to see how out of the world the situation presented can become.

A high school girl confesses her love to a green creature with vaguely humanoid behaviors and they decide to be together forever, in spite of all their initial goals.

Two cat-form beings have an epic fencing battle.

It doesn’t need further descriptions.

We will take an example of a comic-demential anime for a theme that is quite recurrent in Mogeko Castle: the “sexual” theme (presented by the Mogekos on many occasions, in the form of statues or not, and there are also some elements of the game that at least allude to this theme). From this comparison we will then come up with points that will make us better understand why in general the comedy of Mogeko Castle has attracted so much: there are so many comic games with a demential nature, why has this been lucky?

Okay, so… The subject of sexuality is presented to us by the yellow creatures almost constantly.

The various dialogues or burst of anger that we could have between the Mogekos, with the Mogekos or by the Mogekos I think can express that I mean.

And…

Recall the comment that we got to see in the Product History:

“Any attempt at comedy that the game would have liked to have is a little ruined by the fact that we are watching mascot rapist characters whose main motivation is to rape a high school girl […]”

So why, apart from some more serious comments, did the general public laugh while playing Mogeko Castle? Here the choice of the register together with the staging were fundamental.

Due to the register used, the demential one, in many of the moments when referring directly to sex we almost never has the “possibility” of seeing it in a too lousy or disturbing way: in this the characters of the Mogekos also help a lot, from the design up to the ridiculous attitudes, which we will discuss later.

This is why Mogeko Castle was able to treat this theme for 90% of the game in a grotesque way, at times dirty, but never too serious to be taken as disrespectful or of bad taste.

Now, this way of dealing with the “sexual” theme at times reminded me of an anime that I saw a few episodes long ago, when I was just getting closer to the world of anime and manga.

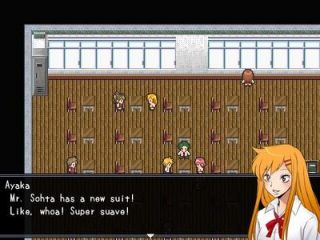

Here is Ayame Kajou, one of the main characters of the anime and dystopian-ecchi manga Shimoneta (also known as “Shimoseka: A boring world where the concept of dirty jokes does not exist“).

By replaying Mogeko Castle and remembering the scenes of this anime, I was able to find various similarities in the marginal treatment of the sexual topic in the two works, especially at the level of first reaction by an average spectator (myself, in this case).

But let’s take just one specific example.

In the image above you can see Ayame’s very first entry. Here, through her “uniform” for the terrorist acts of the organization SOX, she is immediately presented to us as a bloated girl and in general “dirty” for society.

In what scene of Mogeko Castle are we finally presented the Mogeko as “dirty” characters, instead?

But apart from the presentation of two types of “obscene” characters, which are similar to these two scenes?

Both, in addition to having their powerful staging, have a strong context behind them, making them more iconic.

Think about it: why is Ayame’s arrival on the scene so bizarre and it makes our eyes widen in Shimoneta?

You have to know that the anime is set in a dystopia in which the Japanese authorities punish anyone who uses even mildly sexual language or distributes obscene materials, to the point that all citizens are forced to wear peacemakers for the analysis of their every word and movement.

Here, after the presentation of this prohibitive context, we find this girl with underpants on her face, a cloth that could only get up with a minimum of wind and in the act of screaming dirty words to the four winds. Having become accustomed to the environment presented initially, we are surprised to see a character like Ayame.

In Mogeko Castle we are presented up to that point of the game with a mysterious train stop, with no controller, a girl lost in an unknown environment, where there is someone watching her… In the Mogeko forest, then, Yonaka had to escape from beings in her eyes even disturbing…

Who in the end argue like children about who … Must go first, yeah.

Here the Mogeko are presented to us for the first time as ridiculous characters, and the player can not help but laugh at this vibe break, where the game has gone from presenting the Mogeko Castle as something mysterious, together with its inhabitants , to presenting the Mogekos as actually childish and ridiculous beings even on conventionally more “thorny” subjects.

So, having taken the first completely comical scene from the game as an example, why does the whole comedy of Mogeko Castle works?

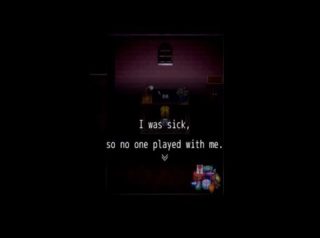

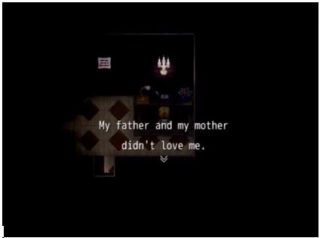

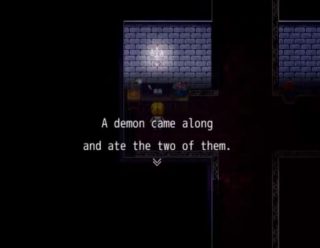

I said it above: because it has a specific context behind it. First of all, Yonaka’s (and player’s) main objective is to explore a castle to find an escape route. Adventure is the genre that is the backdrop to this game in particular, building an excellent base for resting on the demential approach that the game wants to follow. For example, we remember all the parts in which we are told the background of the castle, also through the seven Mogeko Specials (of which we enjoyed the scenes in which they are presented, very effective thanks to the theme that returns for each of them) .

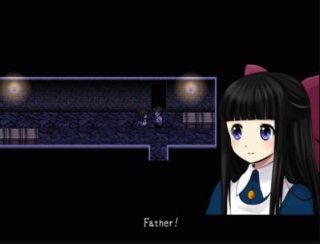

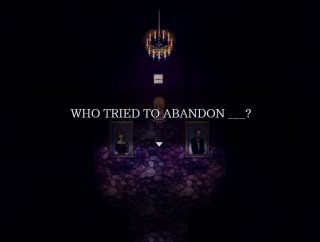

-“Dramatic” Register, with which the plot continues.

There is not much to say about this. Do you know why?

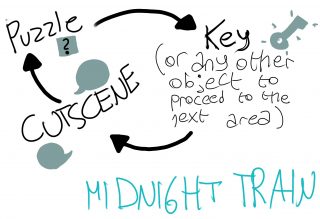

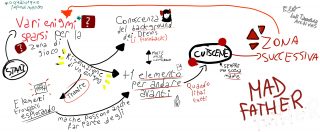

Simply because we have already treated the backbone of this register here in Back to the Future: Mad Father.

Although the comical style is predominant, Mogeko Castle doesn’t give up on treating with certain seriousness certain important scenes of the plot which however develops a type of narrative plot progression (remember what we said before about the “adventure” genre and the several narrative registers).

The use of music, certain movements of sprites, tactics of the CG at certain times (although in Mogeko Castle there are many more, and with more variations, something that I, Ele, I really appreciated) Mad Father and Mogeko Castle share, given that they had the same inspiration, which many RPG Horror titles of today (for better or for worse) are also taking: the audiovisual work.

Mogeko Castle and Mad Father owe a good part of their professionalism to the directing level precisely for this inspiration from the audiovisual work.

On the one hand the presentation of a character who will enter the scene shortly by choosing to show it with a certain pathos, on the other a more “emotional and dramatic” scene from Mad Father

These two shots have clearly taken inspiration from those kind of works, and in many cases with this type of direction actually they manage to have a certain effect on the viewers, and therefore even the games that use these types of direction in many cases (not all cases,pay attention) succeed to give certain emotions to the player.

We can also take as an example the scene of the fight between King Mogeko and Nega-Mogeko.

Come on, how many times in any audiovisual work (at first friction has it reminded me of some type of Shonen anime) that has a minimum of action have you seen this type of shot?

It actually gives a sense of epicity, even if the fight is between two round beings with cat ears.

Mogeko Castle has therefore exploited, a bit like Mad Father did some time before, the “drama”, or to be more general, that type of direction coming from anime series (in this case action or adventure), making it work perfectly in the scenes it wanted to represent.

-Horror Register

The horror register used in Mogeko Castle has no particular characteristics compared to many other titles that we have already had the opportunity to analyze.

What makes it worthy of analysis is the direct comparison with its opposite: the demential register.

In this they certainly help the main danger that Yonaka has to face: the Mogeko species (and Moge-Ko, their dictator on the fourth floor).

As I said a few paragraphs ago, they are very ambiguous characters, and they are of every possible form, especially in function of the plan they occupy.

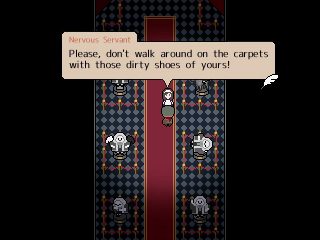

Normal Mogekos are, as I said, beings as stupid and childish as they are lethal. What makes them immediately disturbing is precisely the contrast between these two characteristics, which creates beings who for their whims also practice cannibalism among themselves (many dead Mogeko who are also found before the fourth floor prove it), and in general they are willing to do anything.

[……]

Here we have the perfect example of the contrast that is perennial in the Mogeko species: the words of this little creature may seem, from the tones that it uses, a simple childish whim.

But if we remember that it’s talking about destroying the entire castle (here also a very common hyperbole comes into play when “you get a tantrum”) and in the end take advantage of Yonaka’s corpse… You stop laughing for a moment.

Furthermore, as mentioned above, there are various types of Mogeko. The ones that are used most often to create a horror atmosphere (and are also the protagonists of a bad end) are Mad Mogekos.

…But the horror effect is also given by the indole of the human (or humanoid) characters that we will meet along our way, what they are able to do and what they actually do in various situations.

From these types of expressions in certain moments of the game when we open the menu, we can see that Yonaka is also a fairly ambiguous character, which also makes her disturbing in certain situations.

So Mogeko Castle, with three different registers that alternate, is the demonstration of how important is the way you can tell a story.

At this juncture, we were able to see the same characters every time with a different facet, in addition to the environment itself which often changed shape.

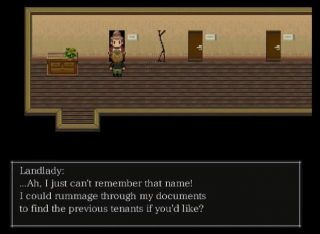

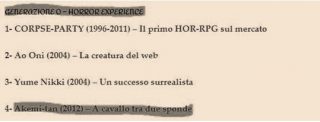

For example, in games like The Crooked Man or others that we have analyzed in Back To The Future, these continuous mutations during the game do not occur, or do not occur so often or between genres that are so different from each other.

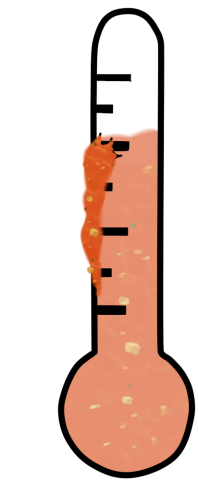

But the time has come to ask ourselves: would Mogeko Castle be able to survive in the market?

We are pleased to find ourselves in front of a perfectly marketable title.

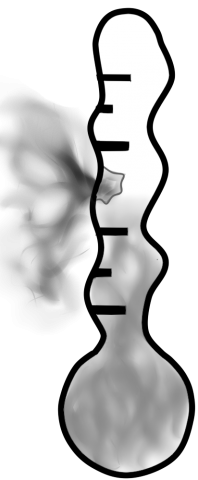

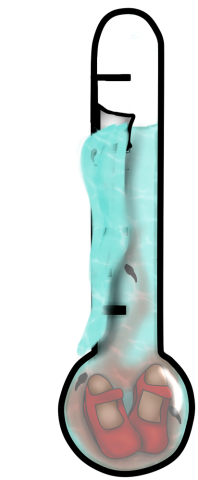

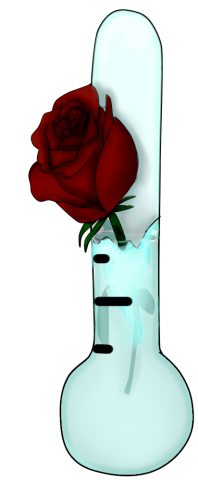

Later we will analyze more deeply those characteristics that at least for us weaken the maximum level on the thermometer.

The personality of the game is strong, with an effective promotion and distribution campaign it could easily reach large numbers.

PACKAGING

If you remember the previous article, we had talked about how dark and dull the colors had gone.

Well, here we have a new spark. To represent the extravagance of Mogeko Castle we have first of all the enlarged tilesets and sprites.

We are often given CG, of which the most brittle ones (in the literal sense of the term or when you meet them the first time) are to represent the bizarre Mogeko.

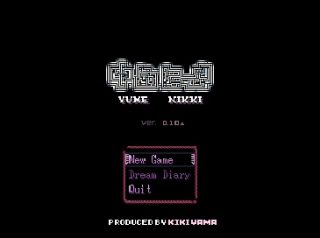

Light blue maps, bloody maps, all devoted to exaggeration to ensure that this is certainly an adventure not to be forgotten and, in any case, also presenting numerous variations for the choice of environments. Also for the title screen.

The latter is dark, with Yonaka in the center and a red eye watching the player.

The menu has very large facades, with many little stars around that accompany the names of the rescues.

RAPPORTO AUTORE – OPERA

I would have to make a note about it: if this game had been in the hands of a professional company, it would have hit the mark.

If on the one hand having done the work of a production company in terms of personalizing the work certainly gives the author many points, on the other hand there was the distribution.

As we have mentioned before, a professional company would perhaps have been able to make the most of it: there is no advantage for the author to remain in the shadows. Such a strong game deserves an equally strong personality, building a myth of the author would certainly have played in his favor.

DIFETTI DELL’OPERA

This title has perhaps one big flaw regarding the ending.

Once Mogeko Defective dies, the plot seems to get lost in delusional events that would like to suggest us to play the sequel that the author has been preparing for years.

The ending could have been an excellent opportunity to close the numerous narrative circles that had opened (above all of explanations on the background of the castle), thus maintaining the linearity of the title until the end it would have remained more easily active, at least in my opinion, player’s attention.

We are not talking only of those endings that leave possibility and interpretation to open questions, but a real hallucinogenic delusion that compromise the comprehensibility of a narrative work, which in this case had little to do with its demented aspect.

To make a small comparison: such a scene we expect it for such a work …

…

…This instead a little less. Especially after a succession of dramatic scenes in which we wonder if Yonaka managed to return home or had only illusions.

Yet despite this, it is difficult to remember this title without a smile for the memories it evokes among fans of the horror current among RPGs.

And with this the First Generation ends.

We could extrapolate a keyword to describe the Horror RPGs of this period, the years in which playing these titles was a trend: variability.

From the variability shown in Mogeko Castle, or the style of The Crooked Man which opposes Mad Father’s exaggerated family drama; from Ib’s minimalism to the sumptuous maps of The Witch’s House the current has stabilized and has found its own way, offering possibilities for wider teams, increasingly intense collaborations with publishers and more defined work agreements. These, dear readers, will be the production stories of Generation 2 titles: storytelling-focus.

The title screen is in black and white with the monster on the side, it looks almost merged with the black background.

The title screen is in black and white with the monster on the side, it looks almost merged with the black background.

Aside from my (Ele) not exact understanding of the third point… The rest may seem normal, can’t it? Graphic improvements, better playability, relocated gems…

Aside from my (Ele) not exact understanding of the third point… The rest may seem normal, can’t it? Graphic improvements, better playability, relocated gems…

Or dunque, ci troviamo di fronte ad un vero maestro che ha saputo riunire insieme due elementi fondamentali per un’opera (videoludica) di qualità: conciliazione tra gameplay e narrazione.

Or dunque, ci troviamo di fronte ad un vero maestro che ha saputo riunire insieme due elementi fondamentali per un’opera (videoludica) di qualità: conciliazione tra gameplay e narrazione.

Yes, you have seen clearly: once again we have a thermometer of professionalism low or at least … Which reaches almost half.

Yes, you have seen clearly: once again we have a thermometer of professionalism low or at least … Which reaches almost half.